Five days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland and three days after Britain declared war, the first wartime Marpole-Richmond Review was published.

One of three headlines at the top of the front page, of the four-page broadsheet Sept. 6, 1939 edition, reads: “Richmond Gets Its Orders For Its ‘War’ Protection.”

Town council was issued several orders from the provincial government in Victoria.

“These, coming from Victoria, give directions for the special precautions for the protection of dykes, water mains, wireless stations, etc., and called for the organization of the first aid corps and the establishment of fire drill in the schools,” wrote the Review, edited and written in part by Ethel Tibbits.

Richmond’s Chief W. A. Johnson was ordered in a letter “to guard all bridges, gas tanks, wireless and radio stations and airports in conjunction with any orders laid down by companies or governments.”

Town staff were directed to form volunteer groups that were to be ready to work on dyke improvements.

The Review reported Reeve (mayor) Grauer had assigned special police constables to guard the dykes and there were 17 special provincial police officers manning the radio towers.

Richmond High principal H. R. MacNeill was directed to ensure the safety of children by revamping fire drills and first aid protocol.

Order and civility in schools were top of mind for the government: “Talk to the children that Canada is made up of all nationalities and that children should not say things that are not becoming, and if they hear of any person that is not law abiding, report it at once to their teacher.”

The article concluded by noting that “apart from this rather sombre session there was little business at Council Monday.”

For instance, one man signed over his house and property to council in exchange for a $20 per month pension. If any of his relatives wished to redeem the home they could do so by repaying the total pension plus interest at six per cent. Meanwhile, water rates were approved for one-bedroom houses.

In an editorial on page two, Tibbits wrote as if the war was inevitable “after several years of threats.” She criticized the pacifist British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and remarked it was “splendid that Churchill is back in the cabinet, as First Lord of the Admiralty.

“With Churchill at the helm there will be action instead of wavering and compromise,” wrote Tibbits.

She said Adolf Hitler was a “ruthless fanatic” who was able to “fool his people” by controlling the media.

She predicted a brutal war, citing the Nazi sinking of the British passenger ship Athenia. Again, she tore a strip off Chamberlain who “dropped leaflets” on Germany instead of bombs after Hitler acted “without scruples, without honour, without any attempt to adhere to the rules of the game.”

Tibbits also rightfully identified the slaughter of Chinese by the Japanese forces in the East.

But she wrongfully speculated the war may not end up in the trenches.

Locally, Tibbits lauded the government for immediately fixing sugar prices and setting rations for local stores. This, after price gouging occurred in the First World War.

“Other commodities should also come under this price control to prevent war time profiteering,” wrote Tibbits.

The following week, Tibbits took another bite at of the corporate world, noting the war would be mechanized and as such “why is not conscription of wealth considered before any move is made to conscript man power?

“Banks, we are told, have been bursting with money.

“Why should not this idle wealth be conscripted for the service of democracy before man power is summoned?” asked Tibbits.

On Sept. 13, 1939, the Review reported how Germans were being quietly rounded up to send to camps and the local Nazi organization became “undesirable” as members, once “loud in their praise of Hitler and his aims, are now less vocal.”

In the Sept. 27, 1939 edition, Tibbits published a lengthy, two-page description of Parliament’s war session, by MP Tom Reid.

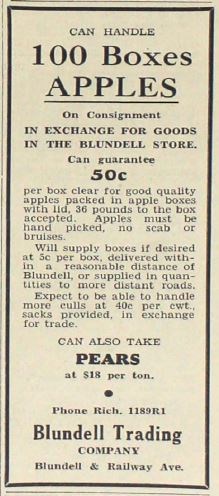

Other news maintained a sense of normalcy in Richmond at the time. Apparently, apples were in abundance this month (“Apples Moving Into Vancouver”). The following week it was reported there was a glut of Gravenstein apples, causing sale prices to drop at the Blundell Store. Apple prices fell to 25 cents for an eight pound bag. People were reportedly peeved that sugar rations hampered their ability to use the apples (perhaps for pies and canning).

And, the Fall Fair was once again popular (“Richmond Fall Fair Again Proves Highly Successful”). At the fair, student Jack Lubzinski was praised by school board chair Arthur Laing for his Pattullo Bridge replica. And the local potato club was lauded for producing 300 sacks per five-acre plot.

Notably, “potato police” had been reassigned. Prior to the war, the Vegetable Marketing Act prohibited Chinese potato farmers from selling their produce and thus “potato police” were stationed on bridges to the mainland following a 1937 potato riot. This was Richmond’s “potato war” era.

Property taxes were debated at council, which seemed to have frequent requests for pensions in exchange for land. Others complained about services.

“Another old-timer, here fifty years, Mr. A. Blair, protested against the dumping of refuse and garbage at the south end of No. 3 Road.”

On Oct. 11, 1939, just over a month after war was declared, total war was in full swing and the Review’s top headline was “Women Asked To Register Locally.”

Local women were wanted for “whatever form of national service they deem themselves fit or willing.”

In her editorial, Tibbits questioned the move to establish seven registration houses in Richmond as a possibly “needless expense.”

And she dug into a sexist undertone of the war, in how women were asked to do the “mopping up.”

“Women have ever bound up the wounds that men have made, and once again this seems to be their allotted place in a war occasioned by the mismanagement of men,” she wrote.

Tibbits continued to question exactly how far-reaching the war would be, noting Italy had yet to make a move and Stalin continued “nibbling away at the cheese” that is the Baltic states (thanks to a non-aggression pact with Germany).

Below her editorial, a small ad indicates “Afternoon Tea” and home cooking for sale at Mrs. Morrison’s home in Riverside.