Enjoying the kid-free zone

By Graeme Wood

I have yet to be shackled by the responsibilities of a wee one and my own father has long since withdrawn his responsibilities for me. So, Father’s Day is a fairly laid-back event, free of duties, usually involving some cold drinks and a round of golf.

My dad raised me right. He was ethical, showed leadership and put me through university. He’s still a top-notch consultant, case in point a recent car purchase.

But while my dad started a family at age 24, I, at age 32 have yet to make that sacrifice (glorious, life-altering journey?). Maybe I’m a bit selfish, reaping the benefits of a good life. That’s probably how it comes across to most Boomers who look at the childless mass that is the Millenials.

In fact, it’s not that. I plan to have children, and my group of friends is well on its way with one lighting the match that has sparked others to do the same.

A big part of the reason why people like me are waiting so long to have kids is because few of us have any sort of job security (journalism), and housing (Richmond) is out of reach for most. Those who are having kids have finally reached a modicum of stability and had help from their parents. Still, they’re diving into a pool with no depth indicators.

I’m lucky to have parents who can somewhat help me. Some — most, I think — do not. So, there’s a lot of late twenty something, early thirty something men enjoying childless Father’s Days.

That said, I have to be honest and say, when I look at a friend or two who do have children, my immediate thought is ‘good God, I couldn’t do that!’ I really (really) like sleeping in on weekends and blasting movies past midnight.

Recently, I went to Spanish Banks with the usual cohort. There was Tired Dad, Expecting Dad, Childless Married Guy with Dog (me) and Single Dude.

I’m still pretty close to Single Dude because I still have a lot of freedom, relative to Tired Dad.

Together we’re clinging to Expecting Dad, knowing we soon won’t see him without a diaper bag for at least six months.

Now, at the beach, Single Dude wanted to continue the evening in Vancouver but Expecting Dad had to bow out for the night. As Married Guy I will, on occasion, entertain the thought (usually to watch a Canucks game) but this time I didn’t and went back into Richmond.

Far removed from this conversation was Tired Dad.

I say this in jest, of course. I know Tired Dad wouldn’t trade anything in the world for his kids.

With my friends’ kids, I play the role of honourary uncle, but I’m also a new uncle to my brother’s newborn child. These kids are known as Practice Baby.

Practice Baby is great. I get to have fun with them while Tired Dads commiserate. We play games; we eat food; we laugh; and then, when Practice Baby starts to cry, our time is over and it’s time to golf.

Dad had pioneering spirit

By Philip Raphael

COURAGE, determination and self belief.

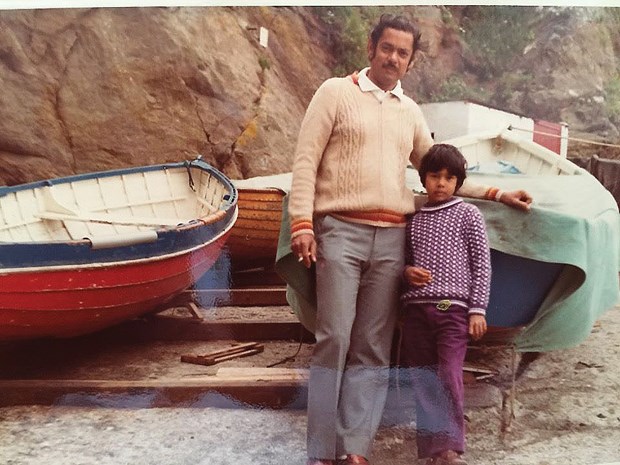

Those three attributes readily spring to my mind this Father’s Day when I think about the path my dad, Terence, took as he guided a family of seven — taking them across continents and cultures on a quest to settle in progressively better lives.

He was just 24 when he decided to pack up my mother and my eldest brother and leave Calcutta, India in 1957, to seek the education needed to become a chartered accountant in what was considered, at the time, to be one of the centres of the financial world — the U.K.

It was the dream of more opportunity, and the chance to learn from the best. But it also presented an odd step backwards as my parents and then eight-month-old brother, stepped off the ocean liner and onto British soil.

“We were so brought up having servants in India that the biggest culture shock was having to wash our own clothes,” he said with a quiet laugh. “Those sorts of mundane chores — we never swept our own floors, cooked, or painted our houses — we paid for that service, and it got done.”

Growing up, I’d heard stories about that type of life in India once the British had left — not living grand, but in a way that included domestic help for the middle class society of the time. It was an offshoot from the life my grandfather led as a surgeon, meeting and befriending a lot of influential people, including a young Rudyard Kipling, author of The Jungle Book, Kim and many other reknown novels, short-stories and poems.

But my dad knew that even with that type of family legacy and the connections his father had, the way to a better life lay overseas, even if domestic life in England required learning a new set of skills.

As my family prospered and grew to include me, the youngest of five children, the goal by the mid-1970s was to seek out better opportunity in yet another corner of the world — Canada. Only this time, the focus was for the children to succeed.

“It was a tough decision — your mum and I were certainly established in our careers. And when I think back on it sometimes, it was one (decision) maybe we shouldn’t have made,” my dad said.

That tinge of regret may allude to the loss of three of my siblings who passed away from illnesses in their early 50s.

Would a move somewhere else, or no move at all have made a difference?

Of course, it’s a question with no possible answer, at least on this plane of existence.

Still, I admire the confidence my father displayed setting up a new life and a new career in Canada in his early 40s.

I am doubtful that I would have had same the conviction to pull up stakes, not once, but twice in my adulthood, and plunge my young family into the relative unknown of new countries and different ways of life.

It’s his pioneering spirit that maybe someday my children will exhibit as it seems to have skipped a generation.

Good Dad/Bad Dad, all in the same day

By Alan Campbell

Bad dad. Noun. Definition: Shaking your head, asking your 12-year-old son, disapprovingly and in utter disbelief, “why, oh, why do you not know how to answer this?” while he stares dejectedly into the abyss that is his algebra homework.

Good dad. Noun. Definition: After being told by your son that he doesn’t want to referee soccer any more because he feels too much pressure, you reveal your pride in him every time he steps onto the field with his whistle to do something you, yourself, never had the courage to do at his age.

Would you believe me if I told you that, just last week, the aforementioned father-son exchanges took place within five Jekyll & Hyde minutes of each other?

If you’re anything like me, you’re probably smiling/cringing and nodding your head knowingly right now.

But, hey, I’ve never purported to be the “Best Dad in the World,” despite wearing the t-shirt Ben gifted me on my very first Father’s Day.

Since that day, being a dad has been a sharp learning curve of astonishment and anxiety chained to a rollercoaster of honour, impatience and “OMG, really?”

There are many times, almost on a daily basis, when I look back and cringe, asking myself why I said that to him and wishing I could reel it back in and offer something more sage or constructive than, “Is that the best you can do?”

Case in point would be me as his soccer coach for the majority of his playing years so far.

This must have been the bane of his young life, with my coaching frustrations, not always of his making, usually taken out on Ben; as I can’t criticise the other kids, right?

How he must have loved my detailed explanations in the car on the way home from games, imploring how he needs to “tuck in” or “get wider and higher” to make more of an impact on the game.

Of course, like anything in life, the trick is to learn from your mistakes and at least try to be better, whether it’s as an inexperienced soccer coach or as a dad to your child.

I like to think I’m a better coach than I was six years ago — I know I make a conscious effort not to talk about the game on the way home, although a wee coaching point often leaks out now and again.

And as a dad to Ben — who will be turning a new and exciting chapter in his own life in two weeks when he becomes a teenager — I try harder than ever, every single day, to think before I critique his every move or decision, even if it’s with the best intentions.

After all, he is a very thoughtful, handsome, intelligent and talented young man (from his mom’s side) and he needs to hear more about that from me than anything else.

What the old man learned in 7 years

By Eve Edmonds

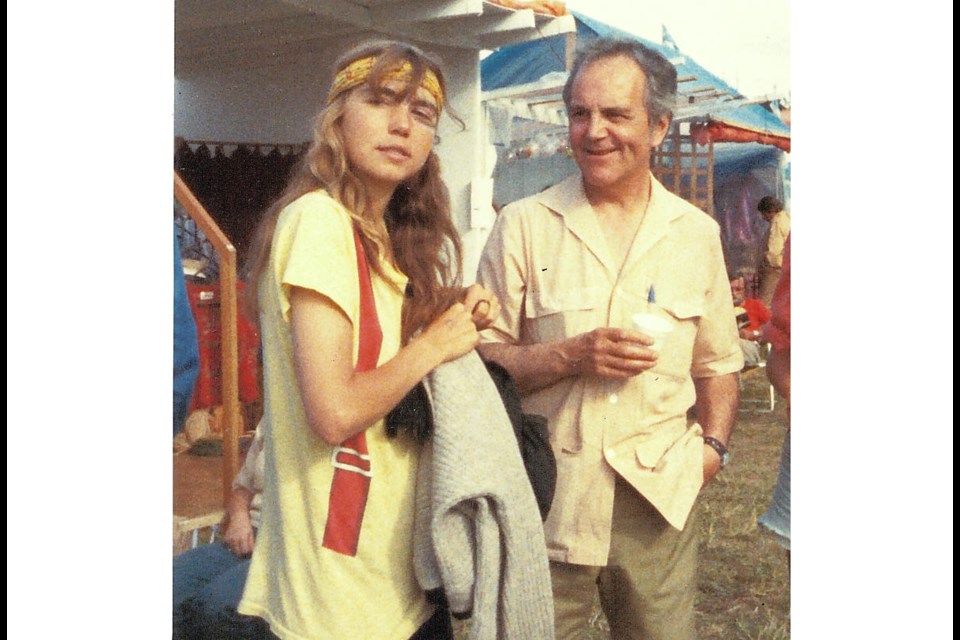

There are a lot of words I could use to describe my father, but conventional wouldn’t be one of them. In fact, he’s so unconventional, he doesn’t even fit the label “alternative.”

We’re talking a vegetarian who bakes bread, meditates, drinks hard, swears like a sailor, reads poetry and is generally disdainful of long-haired, new age hippies.

In other words, not a lot of consistency — a part from the fact he consistently defies any particular mold.

As a youngster, I was generally the envy of my friends for having a funny dad. His kind of humour is well suited to the pre-10 set. I remember one time camping and filling water at a pump when a bunch of kids (aged 5-10) came around and were watching us. My dad suddenly looked up at one of them and yelled, in a slightly goofy voice, “Get off of my bike!”

There was a moment of hesitation (as I died of embarrassment) followed by peels of laughter.

“This isn’t your bike!”

“It is so.”

“It is not.”

“It is so.”

Well, you get the idea. That pack of kids traipsed after him for the rest of the weekend.

When my nephew was about six and he and his family were staying at my parents, he told his mom he wanted to sleep with Granddad, “to see if he’s as funny when he first wakes up.”

My dad was also original. Camping in the rain meant donning bathing suits and playing in the mud, and a snow storm meant a snow picnic.

Once I hit my teens, however, my father’s humour seemed painfully corny, and his side-ways thinking more a source of embarrassment.

I cringed slightly as a classmate questioned me on the bright orange NDP sign on our lawn in Calgary in the 1970s — back when 99 per cent of Albertans voted Conservative.

When I was about 13, we were at some truly boring school assembly. He had gone into a meditative state (did I mention he’d left the United Church and took up Buddhism — not such a radical thing today, but not what dads did at the time.)

I hissed with disgust (as only an adolescent can), “Dad, wake up!”

He calmly replied, “I am awake and probably absorbing more than anyone else here.”

Of course, I didn’t care what he absorbed. All I cared about was looking normal, and he wasn’t helping in that department.

But to quote Mark Twain, “When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.”

Indeed, that has been the case. Well... his jokes are still pretty eye-rolling, but his willingness to look hard at himself and the world around him has been a source of inspiriation and a big part of who I’ve become.

I was ten, living in the heart of cattle country, when he announced he was becoming a vegetarian, because he didn’t like how animals are treated. There was no suggestion the rest of the family do the same, but meat somehow evolved out of our diets. While I try not to look like a zombie at my kids’ assemblies, meditation has helped me through a few of them.

At age 87, he continues to push the envelop: biking, meditating, cursing and enjoying his scotch.

But there’s more.

Last year, while buying him a birthday present, I was in a shop that sold items by First Nations artists. I saw a carved wooden penant of a wolf. My father’s always had a thing for wolves. The artist explained the wolf is often misunderstood. Rather than being vicsous and alone, the wolf is fiercely loyal and devoted to family.

All his colourful character, restless intellect and corny jokes aside, as a father — a true wolf he is.