The 100th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge — arguably Canada’s greatest military victory of both world wars — will be celebrated across the country, and at the site itself in France, on Sunday, April 9.

To mark the auspicious occasion, locally renowned amateur historian Matthew McBride, whose grandfather and great grandfather both fought at Vimy, chose to frame the significant events of those four days by detailing the life of a special soldier, who has a living legacy in Richmond, a century after he made the ultimate sacrifice on the battlefield.

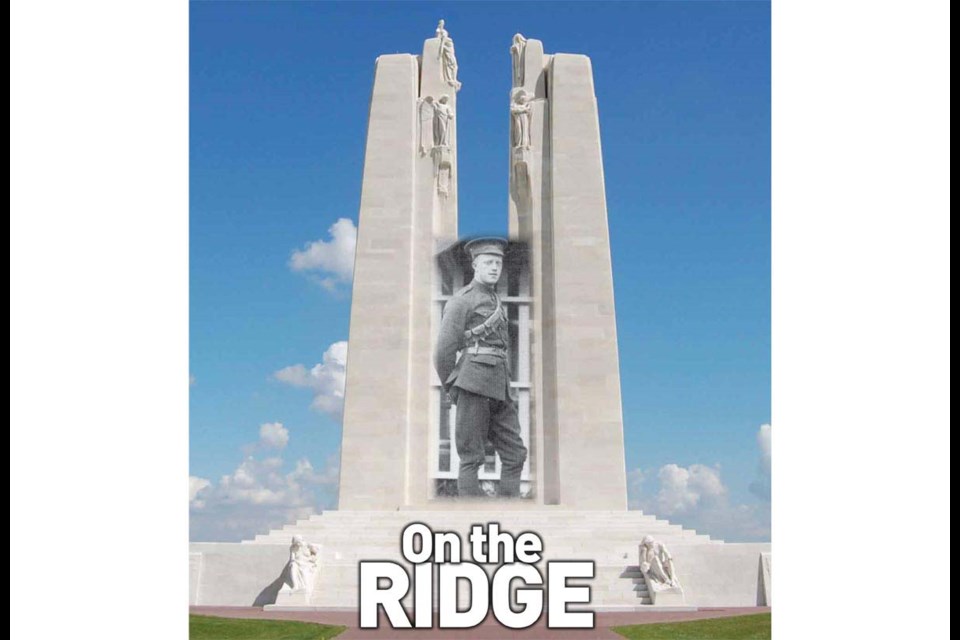

Pte. Edgar Samuel Turnill

Private Edgar Samuel Turnill was born on Dec. 8, 1896 in the Eburne community of Richmond, near to where the Arthur Laing Bridge now stands.

He died April 11, 1917 at Vimy Ridge, France.

His regimental number in the First World War was 116735.

Biography:

Turnill was born three years after his parents, Thomas Harry and Emma Jane Turnill, emigrated from England.

He worked for the canneries — in 1911 he was a foreman at the Britannia Cannery and also worked extensively for the Gulf of Georgia Cannery. One of three boys and two girls, Turnill enlisted in Victoria on April 4, 1916 aged 19 years. He gave as his occupation as “canner.”

On enlistment, he joined the 11th Canadian Mounted Rifles and embarked for England on board SS Lapland, arriving July 25, 1916.

Prior to arrival in France, he was transferred to the 2nd Battalion Canadian Mounted Rifles. Turnill arrived in France on Nov. 29, 1916 and spent part of March 1917 in hospital with a condition called general myalgia.

He was killed, in action, on April 11, 1917 at Vimy Ridge.

Turnill’s mother, Emma, received the memorial cross. His father, Thomas, received the plaque and scroll. Thomas died of leukemia in 1930 and Emma died in 1959.

His name, however, lives on in Richmond, as Turnill Street, near Granville Avenue and Garden City Road.

The “Great War”

In June of 1914, a Serbian teenager assassinated the Arch Duke of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia.

The events that followed in July 1914 set in motion an unstoppable force for the mobilization of armies in Europe, split along treaty lines that eventually led to a near-global conflict that involved 37 countries.

Canada and the “Great War”

In 1914, Canada was a self-governing dominion of the British Empire, but bound by the foreign affairs policies of Great Britain.

Thus, when Britain declared war on Germany on Aug. 3, 1914, Canada (along with Newfoundland, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa) were automatically “at war.”

Canada could, and did, determine the nature and size of its contributions to the war effort, and these issues were the subject of robust debate in Canada.

As early as 1914, the notion of Canada as unique and distinct from Great Britain had been conceived.

The Canadian contribution to the Great War effort was massive in relation to its population. From a population of just under eight million, 619,000 (about seven per cent of the total population) would serve in uniform, and hundreds of thousands more served on the home front.

In 1915, the Canadian Corps was established. During the first years of the war, the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) gained considerable battlefield experience under British command, but in doing so, developed a strong sense of the uniqueness of Canada, and a growing independence in their view of themselves as separate from other colonies or their colonial masters.

Vimy Ridge

By the end of 1916, the war had degenerated into a bloody stalemate.

The French armies at Verdun had suffered unimaginable horrors, and the taste for war was decidedly bitter among French armies.

Thus, for 1917, a plan concocted by France’s Gen. Robert Nivelle — that claimed to end the war in 48 hours with a massive attack all along the Western Front — was guardedly accepted by the Allied armies.

Vimy Ridge is a seven-kilometre high ground of strategic importance, due to its commanding view of the surrounding areas. It’s in northern France, near the town of Arras.

Germany had captured Vimy Ridge early in the war and held on tenaciously, despite attacks by the French and British that cost more than 150,000 casualties.

The task of capturing the ridge was assigned to the Canadian Corps, who would, for the first time, fight as a single unit, with all four Canadian Divisions taking part.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge: April 9, 1917: 5:30 a.m.

Easter Monday dawned with snow and sleet falling, a discomfort that became an advantage for the Canadians as the attack began.

Fifteen-thousand Canadians went “over the bags” that morning in the first wave, and thousands more followed over the course of the day.

By the end of the day, three of the four Canadian Corps had reached their objectives.

The 4th Canadian Division struggled against fierce opposition, but Canadian grit and courage sustained the soldiers, who finally captured the last portions of Vimy Ridge on April 12.

A total of 3,598 Canadians died at Vimy Ridge and another 7,004 were wounded.

Among those killed in the action was a young cannery worker from Steveston, Edgar Samuel Turnill.

Born in Eburne (a former community in the Bridgeport/Marpole area) in 1896, the area was a key commercial hub for Richmond farmers.

Around 1908, Turnill, along with parents Thomas and Emma Turnill, wound up in Steveston, where he grew up in the hardy, outdoor lifestyle common to children of that era.

By 1911, at age 15, he is known to have acted as foreman at the Britannia Cannery (now Britannia Shipyard after conversion in 1917), and is also known to have been engaged in canning at the Gulf of Georgia Cannery.

Answering the powerful call to arms from the Empire, Turnill dutifully headed to Victoria and signed up with the 11th Canadian Mounted Rifles.

His attestation papers describe him as 19 years and four months of age, five-foot six and a half inches tall, with blue eyes and red hair.

A bachelor, his image shows a handsome, confident young man.

At the time of his enlistment, the war in Europe still had a romantic, adventurist air about it. The first gas attacks, (on Canadian troops at Ypres) were 10 days off from Turnill’s enlistment date.

His enlistment process, from April 2-7, 1916 set the stage for his initial training and eventual transfer to England on the troopship SS Lapland, which arrived in March of 1916.

In England, he was transferred to the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles and landed in France Nov. 29, 1916 (while assigned to a “mounted” unit, the Canadian Mounted Rifles in this conflict were not, in fact mounted, but essentially a rifle company).

Turnill was killed in action on April 11, 1917 (exactly 100 years ago next Tuesday) in the final clean-up of the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

Details are difficult to determine, but the initial burial report shows a number of casualties common to the location of his body, so either machine gun or shellfire were the likely cause of death.

He was initially buried in a battlefield grave with a hastily constructed marker to indicate his place.

Turnill was exhumed in June 1919 and reburied in the Thelus Military Cemetery in France, in Plot IV, Row A, Grave 5 along with 300 other, mostly Canadian, of whom 30 have no known name.

What did we lose when we lost Pte. Turnill?

Turnill died in the service of Canada at the very gentle age of 20.

An elder son of a young working-class Steveston family, he left behind both his parents, along with two brothers and two sisters. There is evidence some of his descendants may still live in Richmond.

One can only speculate on what may have been, had Turnill survived and returned to Steveston. He probably would have returned to the cannery and fishing industry; he most assuredly would have settled down, married, and had a family of his own.

We lost the product of his and his descendants’ efforts; the volunteerism he, as most Great War veterans demonstrated, would have served the community, and we lost a valuable family member.

He left behind a gap in his home and his community, where he most likely would have made a powerful contribution.

What did we gain when we lost Pte. Turnill?

Obviously, his efforts produced a victory at Vimy Ridge; an objective deemed worthy of the loss of life by those in command. Later, historians have disagreed.

Canada came back from the Great War with a sense that it was larger than its colonial status, and that it was worthy of a greater voice on the world stage.

During the 1919 Peace Conferences, the Dominion governments were not given separate invitations to the conference, instead expected to send representatives as part of the British delegation.

Convinced that Canada had become a nation on the battlefields of Europe, Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden demanded the country have a separate seat at the conference.

This was initially opposed not only by Britain but also by the United States. The Prime Minister responded by pointing out that since Canada had lost nearly 60,000 men, a far larger proportion of its men compared to the 50,000 American losses, Canada had earned a seat at the conference.

Canada, although having sacrificed nearly 60,000 men in the war, asked for neither reparations nor mandates.

Turnill was one of thousands who died in combat or as a result of wounds to support Canada’s place in the world.

Other Richmond fatalities associated with the Battle of Vimy Ridge include Pte. Walter Steeves, of Steveston, and Pte. Edward Williams, also of Steveston.

These names, like Turnill’s, are recorded on the Richmond cenotaph on the eastern side of Richmond City Hall at Granville Avenue and No. 3 Road.

We should not live in Canada today without acknowledging the sacrifice of our valued sons from days gone by — and we don’t.

Edgar Samuel Turnill is honoured on Turnill Street, just east of Garden City and General Currie roads.

Currie was another profound figure in the Great War. The street signs are adorned with a poppy, the Canadian symbol of Remembrance. Many others are also honoured in the City of Richmond.

Today, you can walk the very same boards that Turnill walked before he went to war, by visiting the Britannia Heritage Shipyard or the Gulf of Georgia Cannery.

He was gainfully employed in both places, building an industry, a community and a country.

We live in the Canada we know today because of their sacrifice.

— with files from Julie Doak, Peter Mitchell, Wikipedia, Government of Canada Archives, “We Will Remember Them,”by Mary Keen, Richmond Public Library, City of Richmond Archives