“Where are the pedals?”

It’s a question Barbara Alink gets all the time when she’s riding her specially designed bicycle that she feels has the power to change the world.

As an inventor, it’s a noble and lofty goal. But it’s one she thinks is attainable.

She hopes her three-wheeled creation, the Alinker, will help people stay active, even into their golden years, and thereby lessen society’s increasing need for drug therapies to treat the results of declining mobility — illnesses such as diabetes are reaching epidemic proportions, especially in North America.

Oh, and when you’re active on the Alinker, you’ll also look cool.

“It has to be cool,” explained Alink, 52, who grew up in the Netherlands and in 2008 came to Richmond where she now lives and works out of a rented basement suite, sleeping in a cramped closet space so she can use the small bedroom as her design studio. “It has to be cool for people to become interested in it, want to use it and get over that stigma of having to use a device to remain mobile.”

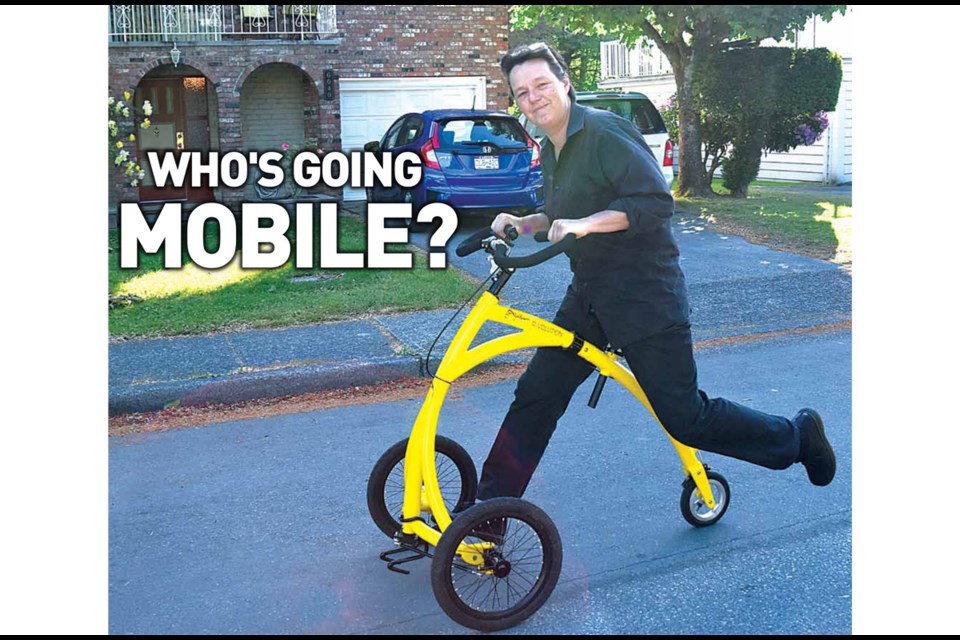

The Alinker, with its bright yellow, curved tubular frame, somewhat resembles a scaled down version of a penny farthing, where the rider sits upright at standing height. It has three wheels — two at the front and a small one at the rear. Steering is done from a set of rectangular handlebars.

And, as mentioned earlier, there are no pedals.

Propulsion comes from the rider’s own two feet as they sit on the bike’s saddle and let their legs do the walking. All the while, the rider remains supported and stable, making the Alinker an alternative to a wheelchair, clumsy walking frame or cane.

“I very often wonder why no one else thought of it before. That’s how simple the idea is. However, the engineering wasn’t that easy.”

Alink can thank her mother, Antonia, for providing the inspiration for the Alinker.

On a trip to her homeland about four years ago, she saw the disdain Antonia had for canes and other walking devices during a trip to a local market.

“She saw some elderly people with walking canes and she said to me, ‘Over my dead body will I be using one of those.’”

At that time, her mother was 74 and had a hip replacement.

“She was starting to have some mobility challenges then,” Alink said. “And she projected herself into the situation of those people she saw in the market.

“With her comment, I actually realized that mobility devices emphasize the disability. And people suffer from that.”

Alink immediately felt that was not right.

“Why can we not have cool walking devices, something that actually supports the user, rather than a disabled body,” she said. “If you look at people with current mobility devices, it quickly becomes clear that they (designers) have attempted to make solutions to physical problems. And they are not very practical, in many ways.”

Walking frames are a prime example.

“You see people bent over, leaning all their weight on them,” Alink said. “And with what is called rollators, walking frames with wheels and a seat you can use to stop and sit down, it shows users want some support for their weight and some relief for their legs.”

The solution was the Alinker’s bicycle-style saddle which comfortably perches the user up at normal eye level so others don’t physically look down on someone in a wheelchair.

“There’s a real social awkwardness to that,” Alink said. The Alinker “is a social equalizer, and it stands for a lot more. Like, I am more than the sum of my physical appearance.

“We miss a lot of human capacity if we judge just on the outside. Having lived 10 years overseas and having worked building schools in countries like Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Darfur, you realize the more you travel that we are all born as naked little creatures who just want to be happy.”

The lightbulb had gone off, thanks to Antonia, and the concept for the Alinker was born.

In the past four years, Alink has used her knowledge as a restoration architect, and her skills to repair bikes — which was one of her first jobs as a youngster in the town of Hengelo, near the eastern border with Germany — to produce the new device.

It’s been a labour of love as she developed seven prototypes with the help of Toby’s Cycle Works in east Vancouver before getting a Dutch bike seller to tweak its design and arrange a first run at manufacturing it in Taiwan.

LAST May, the initial shipment of 200 Alinkers was released for test marketing in Holland, where the already bike-friendly populace took to it well.

“They say that the Netherlands is the best country to introduce a new product,” Alink said. “That’s not because it’s easy. It’s because if you make it there, you can make it anywhere. The people are so set and stubborn in their ways.

“They cycle or they walk. So, the ones who did adopt them — we sold about 100 — the impact has been profound because you immediately change lives.”

Part of that is restoring dignity and respect for those who are disabled.

It’s a result Alink said her grandmother would be proud of, since it was a value she instilled in her granddaughter at a young age.

“My grandmother had one huge value and that was everybody deserves respect, regardless of who you are, what you look like. That was something that was fed to me.

“I don’t even know what it’s like to feel more or less than somebody else. If you’re the president of a country or a poor woman in Afghanistan, if you’re a good human being, I respect that.”

Alink also sees her invention as a way of breaking open the discussion on aging and a general stubbornness for many to include themselves in the subject.

“I think mortality is a huge issue,” she said. “As long as there is nothing wrong with us, we are ‘invincible.’ That’s how we operate as humans. Everyone else gets sick, not me. Everyone else will die, not me. Everyone else might get homeless or disabled, not me.”

Alink said she’s no different. Her father died when she was eight-years-old and she noticed that people dismissed her, rather than talk about the discomfort of death.

“What the hell is wrong? Everybody is going to die. And dying actually makes our lives that much more valuable. That trauma confronts you and makes you think of spending the time we have right.

“So, for me, the death of my father has actually taught me how to live and the importance of living it well.”

Alink said the Alinker can help create awareness about that awkward subject and address the rise in diseases directly related to those brought on by decreased mobility.

ACCORDING to the U.S. Centre for Disease Control (CDC), insufficient activity is the number one cause for half of the population diagnosed in the U.S. with diabetes.

Stats from the CDC also show a remarkable rise in cases. From 1980 through 2014, the number of Americans with diagnosed diabetes has increased four-fold (from 5.5 million to 22 million).

And with one in three people in the U.S. being diagnosed with pre-diabetes, that’s a huge number who could potentially benefit from the Alinker.

It’s a similar case north of the border. The Canadian Diabetes Association estimated the number of diabetes cases is expected to rise by 44 per cent by 2025.

Health Canada states that Type 2 diabetes — a condition that develops later in life is one of the fastest growing diseases in the country with more than 60,000 new cases annually.

“The pharmaceutical companies may like that, but the insurance companies can’t provide that anymore,” Alink said. “With 70 million baby boomers ramming into the healthcare system, we don’t have an option anymore. We need to take charge of our health. We need a paradigm shift.

“It comes down to how do you want to live? That’s the crucial question. Do I want to depend on a medical system that cannot provide for me? Or can I make choices about what I eat and how much I move?

“I think that choice can be quite easy.”

Making choices for advancing her business and helping create a healthier population is what Alink is hoping to do this weekend while in Toronto, where she will be under the glare of the TV studio lights filming an episode of CBC’s Dragon’s Den.

There’s no guarantee she will draw the attention and dollars from the group of entrepreneur investors, or even if her segment will make it to air this fall.

But that hasn’t deterred Alink’s drive to bring her bike to the masses.

“It doesn’t have to be a business that makes a gazillion dollars,” she said. “It’s nice when it does that because you can start subsidizing people with lower incomes to get access to it.

“This is just a vehicle. It could have been another product and my philosophy about life would be the same.”

She’s also started to raise funds through Indiegogo, a crowdfunding website. And the Alinker is getting support through the Coast Capital Savings Innovation Hub at UBC, which is designed to draw together university resources, peer learning, and business networks.

But with all of that going for Alink and her invention, what does one of her harshest critics — her mother — think of the trike without pedals?

“She’s starting to use it now,” Alink said, adding she told her daughter she’s scared of falling like she did on her bike a while back. “And she knows that at her age, 78, falling, you don’t always get back up again. Your recovery is harder.”

“And if you have a disability, you need to learn to use a walker. With the Alinker, you already know what to do because you’ve used it to stay active. Plus, your hamstrings are getting a really good workout, which is incredible good for your balance.”

The Alinker is currently retailing for $1,977 in U.S. funds and can be ordered online at thealinker.com.