It was clear last week at a public town hall meeting that whatever Harvest Power CEO Christian Kasper was selling, Richmond residents were not buying.

Kasper began his presentation to the roughly 150 furrow-browed, arms-crossed Richmondites by first noting his beleaguered east Richmond composting facility had, in the past two months, reduced its organic waste intake by 20 per cent over last year to mitigate the persistent foul odours that have wafted over the city and crippled the well-being of many.

He said the company was in the proposal stage of developing a better composting system and that it would be spending $5 million to fix the problem.

“The composting process is dynamic,” said Kasper. “It’s a challenging thing to get right. We need to get to the standard of no odours. And we need to replace the infrastructure to get to that level,” added Kasper.

Halfway through the meeting, real estate agent and long-time Richmond resident Arnold Shuchat launched the first challenge.

“If you want to come here in good faith, shut it down,” said Shuchat, who co-organized the Stop the Stink Facebook group and has led a group appeal of the facility’s new air quality permit issued by regional government Metro Vancouver.

But shutting down is not an option, according to Kasper. His company intends to continue operating in Richmond after it spent tens of millions of dollars to facilitate the composting of the region’s organic waste.

A long history of complaints after significant taxpayer investment

Harvest Power entered the organic waste fray in Metro Vancouver in 2009, when it purchased Fraser Richmond Soil and Fibre, which had largely handled landscaping waste since 1993. At the time, Harvest Power stated the takeover was an opportunity to demonstrate the company’s “industry-leading technology.”

The following year, Harvest Power received $4 million from the federal Clean Energy Fund to help bankroll its high solids anaerobic digestion facility (the “energy garden”), touted as the company’s “best-in-class” technology to turn biogas into electricity. The federal grant was later complemented by a $2 million investment from Metro Vancouver for improvements at the site, which now operates under the name Harvest Fraser Richmond Organics Ltd. Fourteen months later, in February 2012, it dipped back into the taxpayers’ well, receiving a $1.5 million grant from the provincial BC Bioenergy Network to further the energy garden project.

“This energy garden will not only create B.C. jobs, it will provide a blueprint for other waste-to-energy projects in B.C., Canada and the U.S.,” said Minister of Energy and Mines Rich Coleman, at the time.

By August 2012, the first noticeable trickle of odour complaints were received by Metro Vancouver. The Richmond News reported that the company would be taking steps to improve its operations, after stating it had received an “unexpected” amount of waste. Metro Vancouver also reported it was consulting the public on a new regional odour bylaw whereby companies could face penalties up to $110,000, a figure considered to be “equivalent to the costs of responding to odour complaints in a typical year.”

The odour fee bylaw was scrapped by Metro Vancouver’s board in 2013 after industry stakeholders objected, claiming it contravened food waste reduction goals.

Fewer than 100 complaints were taken in 2012. In December of that year, Harvest Power’s regional vice-president Jeff Leech told the Globe and Mail the company had performed a self-audit of the facility, which was now taking in 190,000 tonnes of waste.

“We have also installed some additional odour control and modelling systems, so we can see where the wind is blowing and send our people to investigate complaints. We have a guy we call our sniffer. When we get an odour complaint, he goes to the area where the complaint came from and documents what he’s smelling, if anything. We are totally committed to fixing this,” said Leech.

By June 2013, then CEO Paul Sellew assured the public the odours had disappeared when the $22.5 million energy garden facility came online, to power upwards of 900 homes under a BC Hydro agreement.

At this point, the regional government was fully on board, issuing the Massachusetts-based company an air quality permit, despite signals that the company was failing to deliver on its promises. Municipalities (whose council members make up Metro Vancouver’s board), would save roughly 50 per cent on garbage tipping fees. The company noted to the Globe, garbage disposal cost $107 per tonne, whereas Harvest Power was charging about half of that; it was recouping its fees by selling soil and electricity.

In 2014 it was a quiet year for the facility and it only received 105 complaints. There was little local media coverage of its operations and the company continued to increase its waste intake and emissions.

Come 2015, to meet Metro Vancouver’s landfill diversion targets, the company began taking in canned goods, packaged meats and cruise ship organics, on top of the new stream of food waste from homes across the region. In June, 2015, the air quality permit expired, setting off a 15-month process to sign a new permit that was marred with increasing odour complaints. Come October of last year, the City of Richmond asked Metro Vancouver to limit organic waste disposal only to those facilities with a permit (last June the province announced regulatory changes to the Organic Matter Recycling Regulation requiring air quality permits for any new facility handling more than 5,000 tonnes of food waste or biosolids). The city made a series of requests to Harvest Power, as well, such as limiting waste intake, which had ballooned to 240,000 tonnes (for which Richmond households contribute about eight per cent of the waste). It also suggested new odour dispersal equipment, such as a stack, be built (Kasper denies that will do any good). Last year ended with 205 complaints related to Harvest Power.

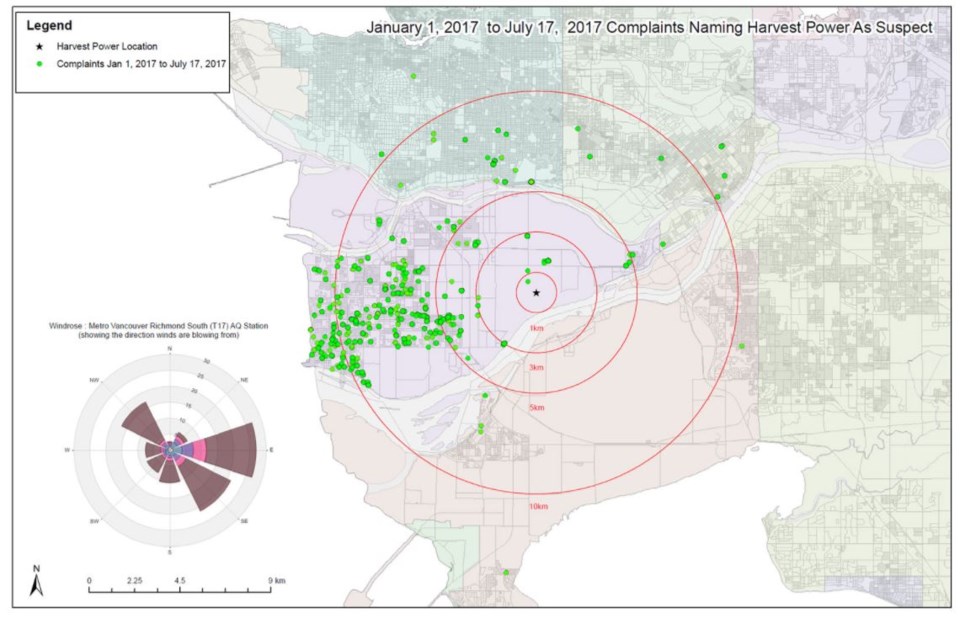

In 2016, however, complaints rose dramatically, particularly in August when the new air quality permit deadline was approaching and more media reports were being issued. As more people became aware of what exactly was causing the odours across Richmond and the complaint hotline was widely publicized, complaints for 2016 skyrocketed to roughly 2,500, to date.

Harvest Power has lost its social license

Many of those complainants appeared before Kasper last Thursday. Many took issue with the fact Harvest Power is appealing the new air quality permit, contesting the “sniff test” whereby the facility can be forced to stop receiving waste, starting in January, if odours are detected for four days within two weeks, five or more kilometres away.

“The reason we are appealing the smell test is because the way the test is structured is unscientific and arbitrary, and it is not fair for us and our 55 employees to not have a test that is scientific,” said Kasper, who indicated — when asked — that the company has no alternative.

“Just shut it down. Leave town. That would be scientific. That would be fair,” replied one resident.

Kasper said the company is also appealing Metro Vancouver’s enforcement measures on jurisdictional grounds (the facility is on federal port land).

Shuchat suggested Kasper was acting hypocritically.

“How are you going to have a standard for zero odours when you don’t accept odours as a standard by any of the tests that are out there? And why should we give you a chance to continue when you haven’t [improved odours] thus far?” asked Shuchat.

“Why should you get a permit — whether it’s federal, provincial, or anything — while you’re in default right now? It stinks and while you’re having this town hall meeting, your lawyers are arguing on a technicality.

“On one hand you’re trying to be neighbourly. You can’t say to everyone here we’re going to do our best but we’re going to still stink it up while we run our for-profit business. That doesn’t pass my smell test. And, frankly, I smell class action. I mean, how long are we going to put up with this?

“Your reputation right now is, we’re going to fight you right now, we’re going to stall jurisdictionally, we’re going to stall on the technical issue of smell tests, and we’re going to run our business and still take the tipping fees and still hold you off with town hall meetings during the shopping season,” said Shuchat, garnering the largest applause of the evening.

Kasper acknowledged the problem was “not good for business” and reminded the audience that the energy garden, which creates the most odours via anaerobic digestion of materials, has been shut down.

Harvest Power has been fined for $1,000 three times in the last three months for operational violations. In 2013, it was fined $57,879 by WorkSafeBC for not implementing an exposure control plan for asbestos. It has never been investigated for concerns related to its emissions.

Health experts say emissions impacting wellness but not a hazard

Meanwhile, numerous people raised health concerns over the emissions that include the likes of ammonia and sulphurs.

On Monday, at a Richmond city council meeting, Vancouver Coastal Health staff addressed councillors on the back of a public letter by Chief Medical Health Officer Dr. Patricia Daly, who stated the odours and emissions do not constitute a public health hazard, as they are “unlikely to cause health effects in addition to ones triggered by the offensive smell.”

In other words, the odours impact quality of life and well-being, noted Daly, but they likely do not cause long-term health effects.

Richmond’s Public Health Officer Dr. Meena Dawar said compost facilities have been studied for some time and have not caused health impacts. She noted volatile organic compounds are mostly non-toxic and dissipate quickly. Furthermore, bioaerosols (such as bacteria suspended in microscopic particles) descend from the air quickly and won’t be found in populated neighbourhoods but they are a health concern for those in and nearby the facility.

She also noted that the odours can exacerbate asthma conditions.

One such resident is Rob Fillo, 34, who told the Richmond News the stink clouds have aggrevated his asthma. The normally politically-reserved Fillo, a graphic designer and musician, is now a catalyst for protest among affected residents.

There are also numerous claims that people are vomiting and getting headaches as a result of the odours. As well, many are choosing not to go outside.

Dawar acknowledged these impacts but likened the odours to car emissions, which also affect people with respiratory conditions.

Even if the odours were declared a health hazard, Dawar said VCH would only step in under the provincial Public Health Act (to shut down Harvest Power) if there were no other avenues to mitigate the problem.

“I believe there is enough authority for (Metro Vancouver) to enforce progressive compliance measures for Harvest Power, if things aren’t improving,” said Dawar.

Dawar, when asked by Coun. Chak Au, said VCH has not studied reports from local physicians on days when odours are reportedly high (noting resources are presently deployed to the region’s crisis of synthetic opioid deaths). But she said overall, VCH has not seen an uptick in asthma cases corresponding with Harvest Power odours.

Residents want clean air . . . and transparency

Resident Jim Tinson said Dawar “overstepped her boundaries” in declaring Metro Vancouver has the tools to address the problem (claiming they’ve failed to do so for four years). He also challenged Dawar’s reliance on studies of compost facilities.

Notably, that the last study on air emissions from the facility was commissioned by Harvest Power itself, according to Metro Vancouver.

Levelton consultanting firm did study odours across Richmond in 2013, for the government. It concluded upgrades to the energy garden “should decrease the geographic extent and magnitude of the odour impacts.”

Metro Vancouver was unable to confirm what specific emissions testing has been done, although a spokesperson said there are 29 air quality monitoring stations across the region.

“Who is measuring the stink clouds that are coming across Richmond? Some of these stink clouds are so severe you run across the parking lot because your body’s telling you to get out. Nobody is monitoring that,” insisted Tinson, who was upset he and other residents didn’t have a chance to address Dawar with questions at the council meeting.

Aside from health concerns, many residents are upset the City of Richmond is not providing details about its contract with Harvest Power. People also want to know what the city could do to exert more control over the situation, including what its stated position is in the appeal process.

City spokesperson Ted Townsend said the details of the contract cannot be made public. But, there may be some recourse available to the city, if the odours persist.

“The city has requested that Harvest Power take steps to remedy odours from the facility within 90 days, per its service agreement. We will be closely monitoring their actions to determine if they are in compliance with the service agreement,” said Townsend.

By Jan.1, the new permit enforcement measures come into effect, despite Harvest Power’s appeal to the B.C. Environmental Appeal Board.