Two hundred and fifteen is an awfully big number, sickeningly big in fact when we think of what it represents: little girls and boys, my kids at that age, your kids, those kids running around the playground — 215 of them dumped like garbage in unmarked graves.

And the dumping is one thing, imagine what those children went through prior to their deaths. (If you’re having trouble with that, try reading the novel Indian Horse by Richard Wagamese.)

And how about the agony families of those children went through never knowing what happened to them?

It’s chilling to think of the mind set that could have let all that happen — a mind set that resulted in, among other things, last week’s discovery of the remains of 215 children buried on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

It’s been said we can’t judge the actions of past generations through today’s lens. In some cases, that’s true, but when has it ever been okay to allow the abuse, neglect and sometimes flat out murder of children?

And when has it ever been okay to not inform parents their child has passed?

The fact the school had only recorded 50 deaths shows it knew full well the atrocity it was committing.

Murray Sinclair, the chair of the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 2009 to 2015 said since the discovery of the unmarked burials, he’s been inundated with calls from people experiencing pain and sadness, as well as a lot of anger.

“I told them about this, and no one believed me!” has been a common refrain.

But as painful as this discovery is, Renée Robinson, a Richmond resident whose parents and other family members went through the residential school system, said there’s also a sense of emotional unloading in finally having the truth recognized.

“I’ve been talking about a genocide for about 30 years now,” Robinson said (in our story on page 10.) “It seems finally that Canada has agreed and sees what we’ve been talking about.”

“It lightens the load for us,” Robinson added. “There’s a lot of emotional labour talking about it constantly.”

But if Robinson is going to set down some of her load, who’s going to pick it up?

We’re hearing more about “settler responsibility.” Frankly, I have a hard time thinking of myself as a settler, but I am a descendant, and I’ve certainly reaped the benefits of that inheritance.

So what does lightening Robinson’s load look like for me?

A first step might be taking a little pair of shoes to the memorial that has been set up outside the Brighouse Library.

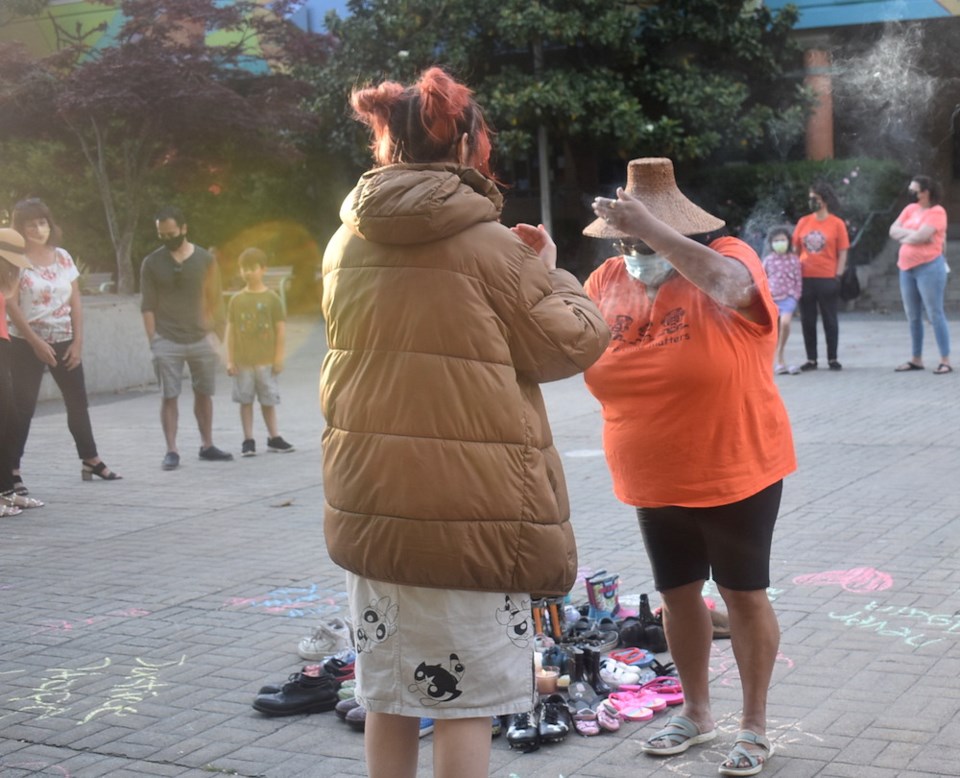

As part of a vigil held Monday evening to mark the gruesome discovery in Kamloops, organizers are asking people to bring pairs of shoes — one for every child dumped in an unmarked grave — to honour them and recognize the footprints they left behind.

It’s a symbolic gesture, and while we can’t stop with symbols, they still matter.

Speaking of, it hasn’t gone unnoticed that while many of our civic leaders were at the vigil on Monday night (and I don’t doubt their sincerity) city council refuses to make a First Nations land acknowledgment at the start of its council meetings.

This has to do with the fact the city is locked in a court battle with a number of First Nations groups over land claims — which in itself gives one pause.

When we truly accept our share of the burden that people like Robinson have been carrying alone, it will be uncomfortable. It may mean looking for more haunting remains, or settling for less in a land claim. But it‘s time we “settlers” share the load in dealing with a tragic legacy.