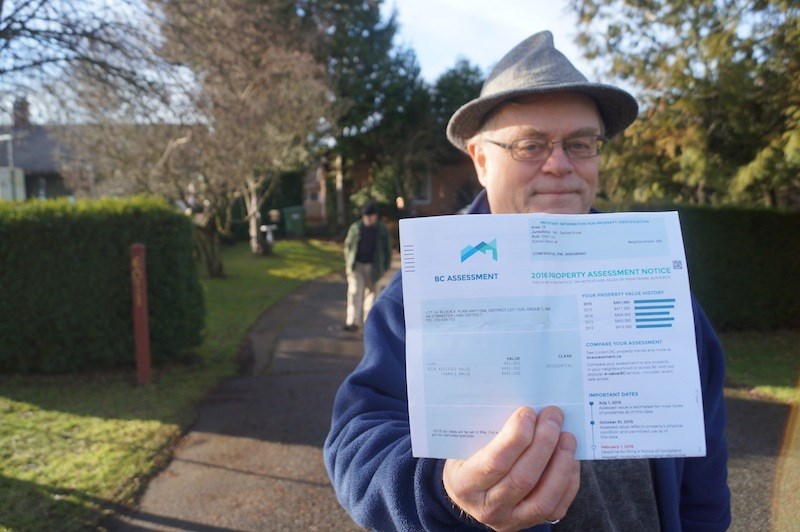

In the past decade, homeowner Don Flintoff, 70, has neared retirement from his job as an electrical engineer and, like many other owners in Richmond, accumulated close to $1 million in equity in his home.

In that same period, digital marketer Ramesh Ranjan, 26, has graduated from Hugh Boyd secondary, received an economics degree from Simon Fraser University, another degree in marketing, from the B.C. Institute of Technology, and landed a job with a local firm.

Despite their middle-class professions, neither Flintoff nor Ranjan are certain about their future in Richmond, a city traditionally home to the middle class but stuck in a region mired in a housing affordability crisis.

It will take a concerted effort, by all levels of government, for Richmond to dig itself out of such a complex problem, according to experts in the field.

Flintoff has been the only owner of his 1988 rancher on Dover Road, now assessed at close to $1.5 million. He’s concerned about his rising property taxes, which he expects to be in the $7,500 range. While he can stomach the bill, at least for now, he has friends who are not as fortunate.

“The ability to stay in Richmond is impaired now because I’d be better off to leave Richmond to capitalize on the value and retire a little better (elsewhere). But we bought a house deliberately to stay here the rest of our lives. We wanted to be close to friends, close to services, close to the hospital. I think a lot of people in Richmond are being forced into the same situation,” said Flintoff.

Eventually, said Flintoff, without a government pension, he will be forced to move away from the community he has lived in for several decades.

“Either that or I surrender my house to the government by way of (deferred) taxes,” he said.

If Flintoff leaves for a less expensive community, he will leave with a large sum of cash in his pocket. Ranjan, on the other hand — a person who has lived in Richmond since birth — would leave with little to nothing.

Home ownership is something Ranjan would welcome with open arms.

“I do want to own property. It’s definitely a goal and I’m saving up for that, but it’s going to take longer than maybe it did for my parents,” said Ranjan, who lives with his parents to save money to buy an apartment.

But that opportunity is not exactly knocking on Ranjan’s parents’ townhouse door.

Ranjan said he has looked at apartments, but feels they’re mostly too small for their price. He did, however, find one potential place to buy, but the development sold out within days.

“You check one day, they’re available, you check the next day and they’re sold out,” he said.

Ranjan said not everyone his age has the “luxury” of staying at home to save money. He also has a full-time job that pays modestly; something not common for his generation.

If he were to move out of his parents’ townhouse, he said he wouldn’t be able to save for a down payment. It’s a position many of his friends find themselves in.

“I think it’s more or less a foregone conclusion that if you want to own property here (Lower Mainland) then Richmond is out of the question because of those market prices,” he said.

But he remains optimistic for his own position.

“I still have some hope that I can live in Richmond, but of course there are no guarantees,” he said.

The problem

Housing affordability has generally meant spending no more than about one-third of gross income on housing, according to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Presently, on average, Richmond’s home price to household income ratio is about 10:1.

According to a Metro Vancouver study, “lower income families are feeling it the most.” It found renter households earning less than $50,000 could spend up to 67 per cent of their pre-tax income on housing and transportation.

Furthermore, the B.C. Non-Profit Housing Agency (NPHA) recently ranked Richmond third worst in the region and 517th out of 522 Canadian municipalities for affordability amongst renters; nearly half of all renters spend more than 30 per cent of their income on housing alone, while one quarter spend 50 per cent.

Building supply

Addressing the affordability problem would take a multi-pronged effort across all levels of government, said NPHA CEO Tony Roy.

Roy, whose organization is primarily focused on renters, said overcrowding is a big problem, especially among immigrant families, so increasing housing supply — ownership supply, rental stock and subsidized housing — is a key priority.

According to Metro Vancouver, from 2011 to 2021, Richmond will require 5,600 rental units in addition to 10,000 ownership units, if supply is to keep up with housing demand.

“You need to get the supply to a point where rents are low enough, so people can save for ownership,” said Roy.

“Right now there are so few units available that the rents will keep going up,” he said, adding there is also concern the recent assessments of single-family homes will drive up the cost of rent for families.

In 2015, the City of Richmond approved an annual record of $997 million worth of development. Via rezoning, it created a total of 2,209 new multi-family units. None of the units were built specifically for renting (but since 2007 the city has added, on average, 100 market rental units per year). In 2015, in Vancouver, 20 per cent of new developments were rentals.

Richmond has stated it needs to better address the rental dearth, but it cannot do anything other than encourage developers of multi-family developments to build rentals. The city is also promoting the creation of secondary suites in new, detached homes.

Roy said developers have little incentive to build rentals, however that may change.

“The federal government has made a commitment to incentivise this by removing the GST for developers building rental properties. I think it’s going to help,” said Roy, noting the Canadian government’s decision to abdicate itself of subsidized housing projects back in the early 1990s has led to a crisis in growing cities such as Richmond.

“Any community that’s really grown up in the past 20 years has tons of affordability issues, particularly for those who are most vulnerable,” said Roy.

A common complaint heard at Richmond city council is just that — the Feds have disappeared.

Richmond MP Joe Peschisolido said a plan is in place to contribute to affordable housing. In addition to already earmarked infrastructure dollars, Peschisolido said the Liberal government would provide $10 billion for affordable housing projects in partnership with all other levels of government over the next 10 years.

In the meantime, the City of Richmond has built a developer-centric affordable housing strategy to fund subsidized housing. Late last year, the city moved to double some development fees that go toward a fund for housing projects. For complexes with more than 80 units, the city asks the developer to build five per cent of the units as subsidized rental units. Part of a review of the strategy this year will be looking at whether the five per cent threshold is adequate and whether income thresholds for tenants of such units should rise.

Local housing advocate De Whalen has called for more subsidized federal housing (such as new co-ops), as well as more affordable rental units.

“We have to start building purpose-built rentals. You can’t depend on the private market,” said Whalen.

With vacancy rates hovering around one to two per cent, Whalen said older, more affordable units are “bursting at the seams.”

Roy is also of the opinion Metro Vancouver municipalities, including Richmond, have ignored market rental housing.

Meanwhile, the provincial government, which plays a larger role in providing subsidized housing, has not provided new revenue streams in years, said Roy.

But last year, Roy noted BC Housing, sold 350 properties to non-profit societies, which will continue to operate under existing or new housing agreements. He said the revenue generated from those property sales should pay for new affordable housing elsewhere.

Curtailing demand

To address demand for housing, the province is able to impose taxes.

This month, Vancouver mayor Gregor Robertson advocated for a speculation tax.

But Simon Fraser University real estate finance professor Dr. Andrey Pavlov is among a chorus of financial critics who believe such a tax won’t work.

“Also, we wouldn’t want to lock people into a property if they make a mistake or their circumstances change,” he said.

Pavlov said he would consider raising property taxes and lowering income taxes.

Furthermore, placing greater restrictions on foreign investors would make sense, he added.

“Taxing foreign investors at a higher rate would be fair because most of them are not paying much income tax in Canada,” said Pavlov.

However the B.C. government has stated it wants to maintain high property values for homeowners. Ultimately, addressing affordability will come down to a leadership decision, said Pavlov.

“The only way to maintain current property values and solve the affordability problem is to increase incomes two or three times.

“I believe we have used up all avenues to enhance affordability without reducing property values already. So the only way to increase affordability, given our current economic and political situation, is to let property values decline substantially,” said Pavlov.

The federal government could also curtail demand via regulatory measures, said Pavlov.

“We need to understand that the housing market is under extreme stimulus from the federal government,” said Pavlov.

First, argued Pavlov, the Bank of Canada keeps interest rates artificially low, fueling a speculation boom in real estate. Second, CMHC provides taxpayer-backed mortgages, he noted.

“This means any major bank can insure their mortgages, whether it’s at a high ratio or not, at very low cost. So banks are not exposed to the risk in real estate, and this keeps them lending even in very risky and/or over-valued markets,” said Pavlov.

International wealth migration, particularly as it relates to Canada’s investor immigration programs, has also impacted the real estate market, according to University of B.C. geographer Dr. David Ley, who foresees further market increases due to the magnitude of offshore wealth coming to the region.

Meanwhile, curtailing money laundering in real estate is also one aspect that needs to be looked at, according to Kim Marsh, a Vancouver-based money-laundering investigator for IPSA International, whose work primarily involves tracking “grey money” for Chinese companies.

He said he’s presently working on a file with “some significant properties in Richmond.”

Marsh said Canadian oversight of financial institutions has largely been nil when it comes to tracking suspicious transactions.

“I think there’s a significant amount of money coming out of China, going into the housing market that’s coming in to be parked. They just want to get it into an investment that is stable. I think this kind of investment is causing the market to go up,” said Marsh, noting wealthy Chinese nationals, especially those running state-owned enterprises, are seeking to pull their assets out of the country.

In turn, investors are paying above average prices for foreign real estate.

“So you end up with properties at inflated prices,” said Marsh.

Marsh said Canada needs stricter anti-money-laundering legislation, particularly as it applies to lawyers performing conveyances and real estate agents reporting suspicious transactions to the appropriate Canadian government agency (FINTRAC).

In August, the Canadian government announced it would audit the real estate industry.

“My sources say it ain’t gonna be pretty,” said Marsh.

What each level of government can do to fix the crisis:

Municipal:

- Increase housing supply

- Collect affordable/social housing development fees

- Advocate to higher levels of government

- Regional governments coordinate supply/demand

Provincial:

- Taxation measures (vacancy tax, speculation tax)

- Foreign investment restrictions

- Fund subsidized housing projects

Federal:

- Set interest rates

- Set parameters for investment (down payments)

- Foreign investment restrictions

- Fund subsidized housing projects

- Better regulation of real estate investments and oversight of banks