For 125 years the Steveston Hotel — once known as the Sockeye Hotel — has served beer and spirits to the village’s thirsty throng that has gathered to meet and share stories.

Now, after a century of transformations, the Buck and Ear pub is set for yet another, with the purchase of the building, by restaurant franchise company, Joseph Richard Group.

One may expect that the change will conform to a Steveston village that’s in the midst of yet another round of gentrification. Shops that once sold fishing nets and power tools are being replaced by chic boutiques and trendy hangouts befitting the new money dotting the perimeter of the village in the form of high-end condominiums.

The changes to come have sparked heavy interest from the Richmond community, past and present.

“You could write a book of all the goings on down there,” said Darren Wong, 55, a graduate of Steveston secondary school in 1979, who believes that while there are tales to be told, any author is likely to encounter a ‘what happens in the Steveston Hotel stays in Steveston Hotel’ attitude.

“No one wants to have their dirt revealed,” Kevin Coles, 46, cracked wise to the Richmond News, following a heated debate on social media regarding the ownership change.

Hotel opens in 1885

The stories began around 1885, when the hotel was built, according to documents found in the Richmond Archives.

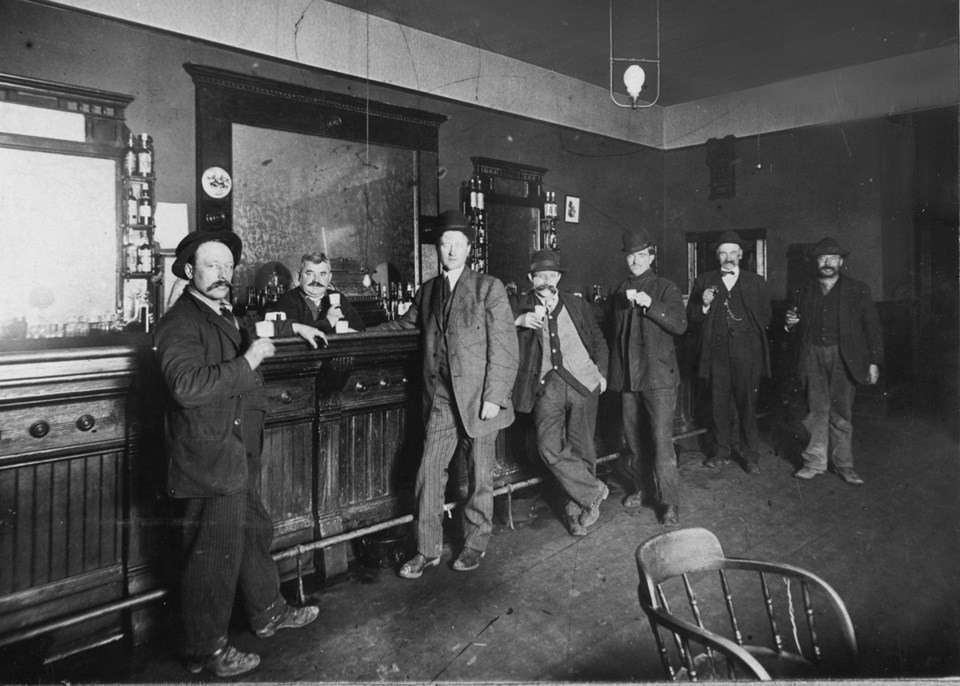

Imagine, if you will, putrid-smelling crusty fishermen coming off a week-long salmon run in the Strait of Georgia, thrusting the new saloon doors open with a crash, taking their place at the bar and ringing a bell to order a round of whatever’s on tap from the dapper looking bartender who’s just spit-shined the glasses for the evening.

Drunks? Yup. Fights? You bet. Good times? You better believe it. Park your horse on the boardwalk with a pail of water and pick him up tomorrow.

Yet, for the first decade of the hotel’s history, de facto prohibition ruled in Steveston since the municipality of Richmond didn’t hand out licences.

But salmon was gold and abundant. And those who fished it were young, full of testosterone and lonely — a perfect storm for the vices of the day.

Illegal gambling reigned supreme in Chinese houses, and booze flowed as fluidly as the salmon swimming up the Fraser River.

In 1896, a public petition finally led to town council licensing about 20 hotels in the village, including the Sockeye, but that did little to change Steveston’s “dreadfully immoral condition,” according to Rev T. Crosby’s 1899 account in the Methodist Recorder.

“Many nights you could not sleep on account of drunken Indians, and more degraded white men carousing around with poor, deluded women,” Crosby is quoted as saying in Duncan and Sue Stacey’s book Salmonopolis.

“Another poor fool, with 200 fish in his boat, selling them at 20 cents, no sooner gets them sold than he is off to one of the holes where liquor is sold, and is soon rid of the money, and in a drunken quarrel has his head split open,” Crosby adds.

At the insistence of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, city council enacted the Sunday Observance law in 1897, which preceded the Public Morals bylaw in 1902, prohibiting profane language in public.

Pub known as political hot bed

The famed hotel was also known as a poltical hot spot. In 1900, it was used as the headquarters for the Sixth Regiment Duke of Connaught’s Own Rifles which came to Steveston to quash potential riots during the fishermen’s strike. Word got out that the officers were coming to town, and the riots never happened. Nevertheless, the regiment enjoyed the village and set up camp behind the hotel.

Federal prohibition occurred during the Great War from 1916 to 1921.

But, as police were occupied with illegal stills, local doctors prescribed Jamaican rum: $2.50 for the rum and $1 to buy a permit (First Nations people were not allowed to consume any alcohol).

If fires are thought to be an act of God, then it has been God’s will to keep the Steveston Hotel open for all these years; it’s one of few buildings that survived the great fire of 1918. Although records of the hotel’s early years were destroyed in 1912 in another fire that destroyed the Steveston municipal hall.

As it does now, the two-storey building consisted of a dozen or so hotel rooms up top and a coffee shop and beer parlour/pub down below. However, over time the shape and façade of the building has been altered several times.

Hotel turns to brothel in ‘30s

As it did in most places, the Great Depression loomed large over Steveston and the hotel was turned into a brothel to keep it operational. Although records are few and far between of this time, we know Steveston was a jumping point for rum runners to the United States during the prohibition era, so it wouldn’t be a bad guess to assume people who frequented the parlour at that time were in the know of such operations. Stacey’s book notes fishermen bought bottles of whisky for $5 and hoped to sell them to American boaters for $15.

After the Second World War the Steveston Hotel was believed to be the only place to wet one’s whistle in Richmond until the Skyline pub opened in the late 1950s.

In the 1950s, the hotel was described, in archived records, as a place for fishermen to get cleaned up for just 50 cents a night.

Continued signs of trouble in the bar could be gleaned from an archived story told by bartender Mike Musyi, who slung drinks from 1958-1973. Musyi said new owners insisted on waiters wearing bowties so that regular ties wouldn’t fall in drinks or risk being grabbed by “unruly patons.”

Coun. Harold Steves, 78, was in his twenties in the 1960s and recalls a rough crowd of fishermen that nevertheless “took their politics pretty seriously, especially after a few drinks.”

In 1965, on one occasion, said Steves, Social Credit politician Bob Strachan spoke at the community centre and the debate carried over to the hotel pub where a fistfight ensued.

“They had some pretty hefty bouncers back in those days. The fishermen were quite an independent lot, you might say, and not inclined to tow the line,” said Steves.

Steves, a blossoming politician at the time, recalls the decade in which Rev. John Patrick lived at the Steveston Hotel (1957-1967).

“He asked to meet me one day to discuss some issues and he told me to come to the back of the pub. I asked him ‘why are we meeting here?’ He said ‘this is my office, this is where all my clients are.’”

In the following two decades, the hotel acquired more of a “mixed crowd,” said Steves.

As the fishing industry subsided, so did Steveston’s brand recognition as a hotbed for labour and union activism; since the early 1970s, Canada’s conservative parties have held control of the area.

“I’ve seen Steveston from the early 1980s when we rode our bikes to the Garry Point dunes and Steveston was a ghost town,” recalled Coles.

“I did summer work at the packers, too, so I’ve seen all the changes, good and bad. I’m not against all of it; change is inevitable, but I think people have overreacted on the Buck, like it’s some sacred place. It’s a bar and as long as they’re not tearing it down, it will probably retain its clientele,” said Coles.

Wong also remarked on how the economics of the time was a factor in the Buck’s identity.

Union jobs at BC Packers drew many teens away from high school to a pay cheque, he said.

“It was a hard job, so they played harder. You can understand what kind of atmosphere it would have been at the Buc,” he added.

Bucaneer known for strippers

The ‘Buc’ Wong refers to is the Bucaneer Room, the longheld name of the hotel’s pub before it became the Buck and Ear in 2000 (it was also the Third Avenue Pub). During the 1980s, adorning the boxy, window-deprived stucco building, fit for an Eastern European mining village, was a large pirate sign overlooking the café at Third Avenue and Moncton Street. Below, tinted port-hole-style door windows welcomed patrons for cheap drinks and stripper shows in the beer-soaked hall.

“I can tell you, I used to go to the Buc and (sometimes) never had to pay for a drink because someone was always buying. They had a bell and if you rang it, it was drinks all around; it happened quite a bit,” recalled Wong (the bell still exists).

“By and large, it was all locals (in the bar) and everyone walked or took cabs. A lot of people were intimidated by the reputation of the place, but it was just that, a reputation,” said Wong.

In its last two decades, the reputation the Buck and Ear earned was two-fold: One, it maintained its status as the place to have an adult beverage in Steveston. Two, it was charged several times for over serving patrons, culminating in a multi-million dollar lawsuit.

On June 12, 1999, recent graduate Eric Tremblay had his life forever changed after a drunk driver hit him on Chatham Street. BC Supreme Court ruled the Steveston Hotel was 50 per cent liable for the actions of driver Henry McWilliams because bartenders over served him and failed to find him a ride home, despite being warned of his condition. The case was precedent setting, as at the time of the ruling (2005) it was the largest percentage of liability portioned out to a licensed business in Canadian history.

In September, 2009, the Buck had its licence pulled for five days and was fined $5,000 for numerous breaches.

Yet, it has always been a successful meeting point for locals, hosting the village’s only beer garden on Canada Day festivals and, recently, being the host venue of the Steveston World Cup celebrations.