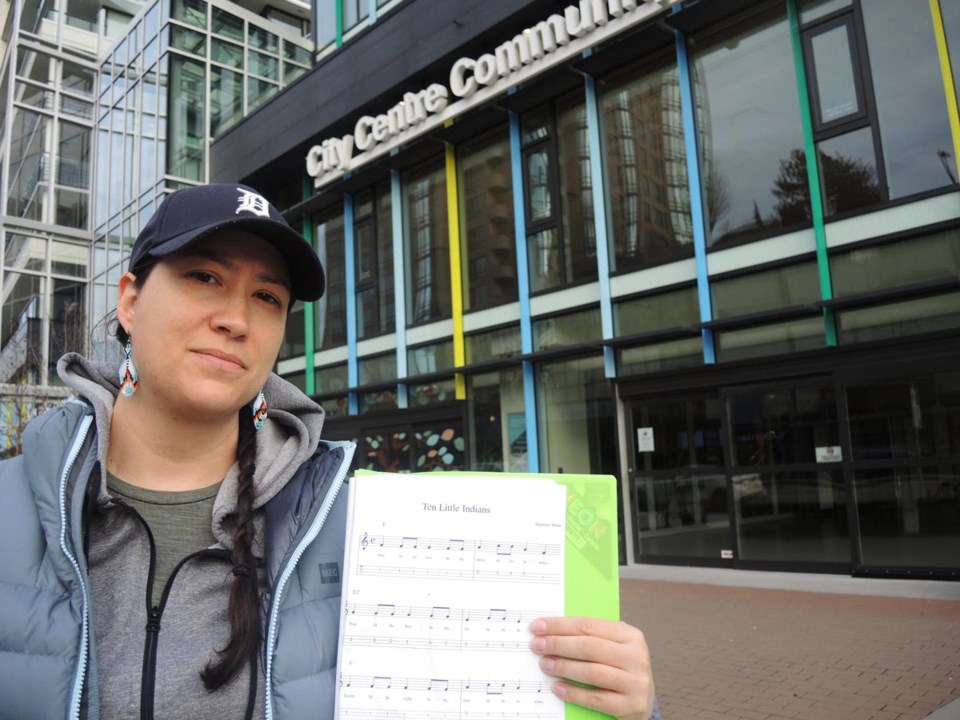

So a kid comes home with sheet music for Ten Little Indians, handed out by her music teacher at a local community centre.

Not surprisingly, her mother, who just happens to be indigenous, is outraged. And she’s not alone. It is outrageous that this material is still circulating in a public, family facility.

However, what strikes me about this story is not just how far we have to go, but also how far we’ve come. I remember using that very same sheet music during my piano lessons as a kid. No one thought anything of it — at least, no one in my white, middle-class, world did. Thankfully, now, we do think about stereotypes and misrepresentations of various groups. Reading through my kids’ social studies textbook a few years back, I was amazed at how radically changed the narrative is regarding First Nations.

But while words matter, be they in a textbook, sheet music or official apologies for past wrongs, there is still that niggling thing about lived reality. Right now, families in 63 First Nations communities don’t even have clean drinking water, for goodness sakes. And let’s not even get started on systemic racism, poverty stats and incarceration rates.

This disconnect between words and reality reminds me of something I heard a young indigenous woman say: “I can accept your apology for stepping on my foot, but first you need to get off my foot.”

This Christmas, I gave my son 21 Lessons for the 21 Century by Yuval Noah Harari, who also wrote Sapiens: A Brief History of Human Kind and Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. In his lastest book, Harari argues that humanity currently faces three existential challenges: nuclear war, environmental destruction and technological disruption. And while he paints some truly terrifying images of what could lie ahead, his overriding message is that our future is dynamic. Yes, things are bad, and they could get worse, but today is better than yesterday, which means tomorrow could be even better.

It should be noted, Harari thinks not in decades or even centuries but millennia. From that perspective, fewer people are being killed in war today than at any other time, and more people will die of obesity than starvation. (Not that dying of obesity is okay, but it does shift the conversation.)

I bought the book for my son, 21, because while young people need a clear view of the challenges ahead, they also need a sense of hope and empowerment. Yes, Ten Little Indians sheet music is still being handed out, but the fact that’s a story is, in itself, progress. And about progress, Harari argues that the only reason we sapiens have risen to dominance is because of our ability to cooperate on a large scale. And the only way we can ensure our dominance, or even survival, in the future is, again, large-scale cooperation. In other words, think globally. Climate change doesn’t respect national borders, nor do migrants for that matter.

So here’s my resolution for 2019: quit fretting over an uncertain future, build on successes and recognize we are inextricably linked to every other species on the planet.

It’s a big list, and we know what happens to resolutions by February. But it’s the ol’ college try to ensure this planet remains hospitable for our grandchildren. Happy New Year.