In 2007, the Oxford Junior Dictionary (first published 1978), for ages 7-11, brought out a new edition from which about 50 words had been removed and replaced by others. The discarded words concerned the natural world; in their place were words relating to 21st century technology. A newer edition (2012) has pulled even more nature words. This culling prompted an outcry from 28 authors, including the Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood and the British writer Robert Macfarlane, who signed a petition sent to Oxford University Press.

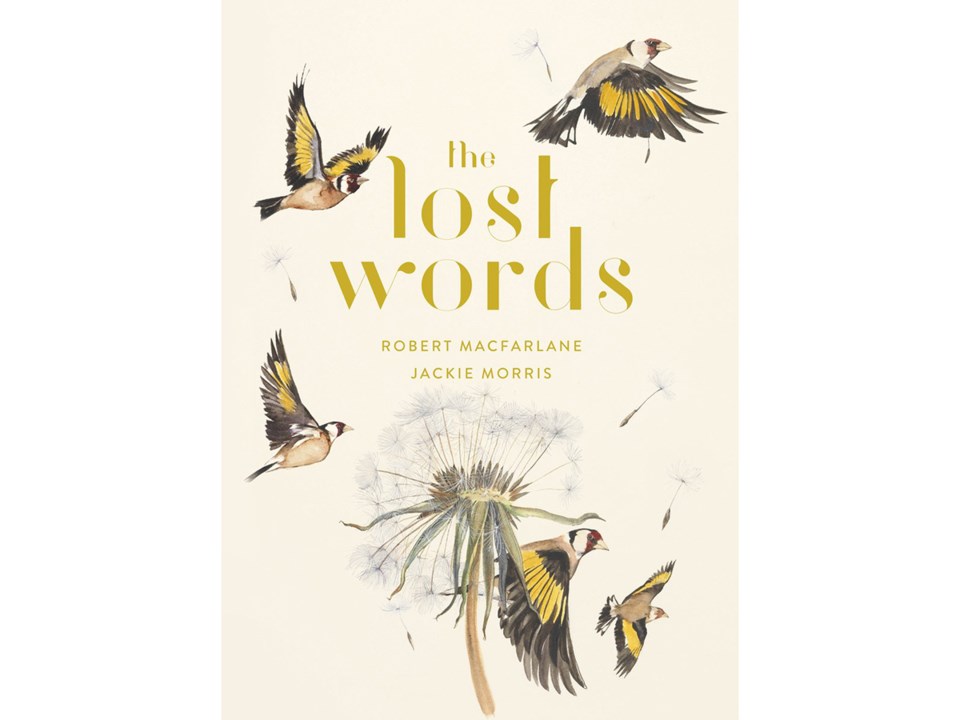

The Oxford Junior Dictionary’s lamented editorial decision inspired Robert Macfarlane and the illustrator Jackie Morris to create The Lost Words, published in 2017. With gorgeous illustrations and magical spells, Macfarlane and Morris gloriously revive 20 of the words that had been sent to the gallows by the Oxford editors – acorn, adder, bluebell, bramble, conker, dandelion, fern, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, lark, magpie, newt, otter, raven, starling, weasel, willow and wren. Fortunately, Richmond Public Library has copies of the book, and I encourage everyone who hasn’t yet perused it, to do so as soon as possible.

Why is it considered so important not to expunge words that pertain to the natural world? The answer is simple. If we don’t have a word for something, we don’t distinguish it. If something is not linked to a word, we can’t name it. And if we can’t distinguish or name it, it doesn’t have an identity. It doesn’t register with us. We don’t see it.

Think of children walking through Minoru Park, past the magnificent oak trees, unaware that what they’re crunching underfoot, or kicking along playfully, are acorns – because they can’t name them. If the children knew they were called acorns, they’d soon know they were the nuts that have dropped off the trees. They’d discover that packed inside the tough shell is everything needed to make a gigantic oak tree. They’d learn about the cycle of life.

Now think of those children encountering various black-feathered birds in Minoru Park. What if they simply dismissed them as plain black birds? Surely the children’s imagination would get fired up if they could name them as crows or starlings. Knowing their identity, they’d find out more about them. They’d eventually be able to recognize them in flight – a murder of crows or a murmuration of starlings, sweeping through the sky in their distinct formation.

The rationale of the Oxford Junior Dictionary’s editors was that decades ago, many children lived in semi-rural environments, in close contact with nature. Today, no matter where in the world, most live in built-up areas and are in closer contact with computers than with nature. Those who opposed the deletion of nature words argued that children derive many benefits from playing out of doors, while they can suffer serious consequences if they’re disconnected from nature. As Robert Macfarlane perspicaciously observed, we don’t care about what we don’t know, and by and large we don’t know what we can’t name.

Words help us to see and know.

Sabine Eiche is a writer and art historian

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)