Kids these days can’t know if their childhood is better or worse than that of children decades ago, but we – the older generation – can make a pretty good guess. A recent opinion piece in The New York Timesclaims that childhood has been ruined. Within a matter of hours, the story had received comments from about 1,300 readers, almost all concurring that their own childhood had been simpler and happier.

An alarming and fast growing percentage of today’s kids are diagnosed as depressed, anxious, miserable and suicidal. Why is this happening? Psychologists and pediatricians have pinpointed various causes, including too much screen time, stress at school, and structured, micromanaged activities after school. The bottom line is that children are being starved of the free time to be who they are – children – at their own pace.

In the 1950s and early 1960s when I was a child there were no personal computers, recess and lunch-breaks at school were leisurely, tests were neither stressful nor too frequent, and my parents did not ferry me from one scheduled activity to another after school or on weekends.

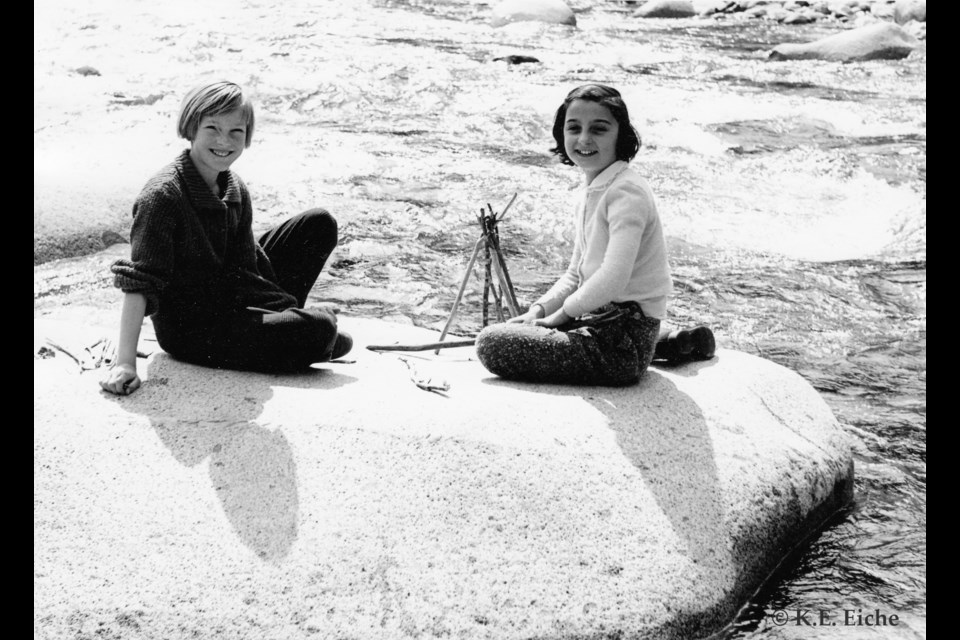

My best friend and I were allowed to play freely. We romped in our yards, in nearby vacant lots overgrown with greenery, and in the great outdoors when my parents took us on camping trips. Inspired by what we read about North American Indians, we built lean-to shelters out of branches and leaves. We tried learning primitive skills such as lighting fire by rubbing two sticks together. We explored the world immediately around us.

If the weather was bad we found ways to amuse ourselves indoors. Our fantasy was unbounded. Board game pieces that looked like streamlined chess pawns became our make-believe people when we played house. The make-believe parents were always called George and Martha. Our pretend house, a rectangle outlined with Lego blocks, was furnished mostly with beds – which in reality were metal springs that we’d removed from clothespins. We played with paper dolls, too, sometimes cutting out clothes for them that we’d drawn and coloured ourselves. We acted out stories with these paper dolls and the make-believe George and Martha. Our kids’ games didn’t rely on any apps, they derived from our imagination.

The word kid, properly speaking, refers to a young goat, but it was a slang term for child already in the late sixteenth century. By the early nineteenth century, kid was upgraded from slang to colloquial, and at the same time it was also used as an informal verb meaning to deceive or fool someone in a playful manner. There is a certain logic in referring to children as kids, because if allowed to be free, children do jump and run like frisky young goats. In all likelihood, if the term hadn’t been coined centuries ago, when children could run wild and be frisky (until they were forced into the labour market, that is), it would not have been coined today – when children are tethered to computers and other electronic devices.

Sabine Eiche is a writer and art historian.