I used to think I could easily spend hours in a store looking at children’s toys. Until recently, that is. Late last year I walked into a toy store here in Richmond. What I saw shocked me. Most of the toys crowding the shelves were a far cry from the classic, traditional toys I remembered from Germany. They were digital toys and toys linked to the entertainment industry. They were the latest fashion in children’s products.

The trend in modern — whether technological or “celebrity” — playthings has been growing for a while, I discovered. Over the past fifty years or so, toys have been marketed directly to children, first through television, then through social media and screen use. As toy manufacturers and retailers know well, children are defenseless against their advertising strategies. They also know well that adults often relent, for one reason or another, and buy whatever they’re pushing.

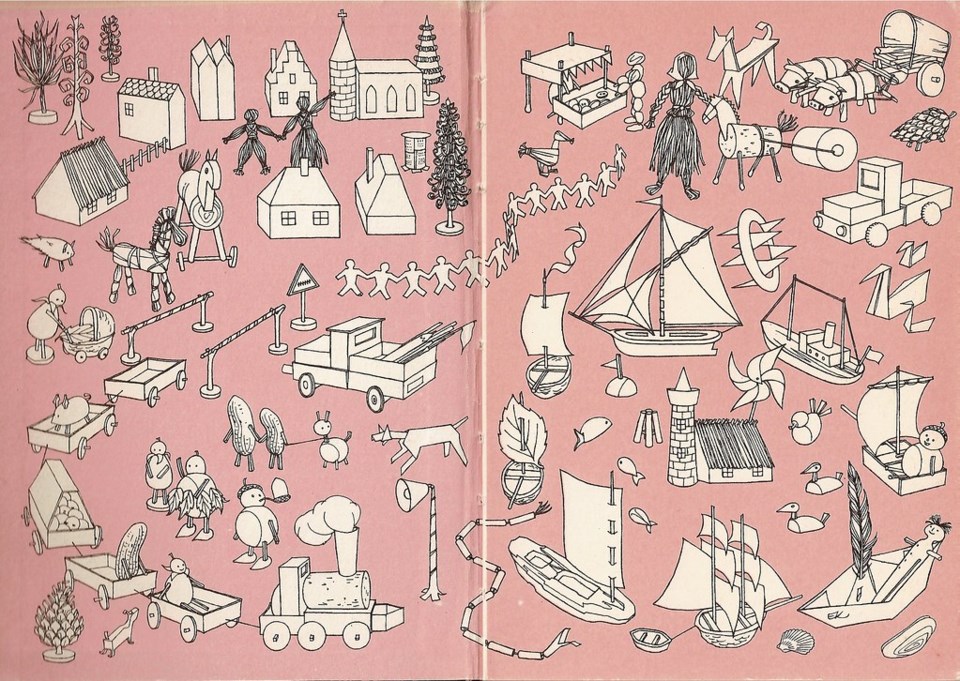

Our Earth is being suffocated by a surfeit of stuff. There’s too much of everything, much more than we either need or want. Children are not left untouched by this dilemma of excess. In December 2023, the Washington Post ran an article discussing why fewer toys are best for kids. According to experts on childhood development, “having fewer toys around leads to deeper engagement with each of them, which promotes creative thinking.” A team of researchers ran tests, observing how toddlers behaved in two different situations — one in which there were four toys, another in which there were 16. With fewer toys, the toddlers “engaged more deeply in play with each toy, interacting with the same item for longer and in more ways.” Toddlers used their imagination to make believe. Their curiosity led them to explore and to learn. In fact, the plaything needn’t even have been a manufactured toy. It could have been a cardboard box, which the child’s imagination can turn into any number of things — a tunnel to crawl through, a sled to slide with, a cave to hide in. “Simpler toys (and fewer toys) leave room for higher-quality play.”

Five years ago, in January 2019, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a clinical report — “Selecting Appropriate Toys for Young Children in the Digital Era.” Parents were advised to select high-quality “traditional” toys instead of elaborate digital ones. Aleeya Healey, one of the authors of the report, stated, “The less bells and whistles a toy comes with, the more it lends itself to creative play and imaginative play.”

Children have a special way of playing with what are called role-play toys, which can be dolls or stuffed animals, or any object they invest with a personality. Children endow them with emotions and feelings and talk to them about such matters. It’s considered a first step in learning to interact with other people.

Toys don’t have to be manufactured. Out of doors, children come across countless objects that have the potential to be transformed into something magical. Searching in nature for items to turn into playthings has the added benefit of letting children learn to identify what they’ve collected. Remember Robert Macfarlane’s 2017 children’s book, The Lost Words? He wrote it to underline the serious consequences of children being disconnected from nature, unable to see what’s before their eyes — because they lack the words to identify what they see.

To put it bluntly, I’ve reached the point where I believe that modern toys are to the toy industry what ultra-processed foods are to the food industry — both have benefits that are questionable, except to the industry, whose only concern is profit.

Modern toys run the risk of providing children with processed imagination. If we want our children to be nourished by their natural imagination, we’ll have to sift carefully through what’s offered online and in the big toy stores.

Sabine Eiche is a local writer and art historian with a PhD from Princeton University. She is passionately involved in preserving the environment and protecting nature. Her columns deal with a broad range of topics and often include the history (etymology) of words in order to shed extra light on the subject.