Usually it’s a subject I know well, or an experience or observation, that provides the inspiration for my columns. In extraordinary times, however, I wander into unfamiliar territory – and right at the moment, not much feels ordinary or familiar, with the coronavirus pandemic continuing to hold our lives in its grip.

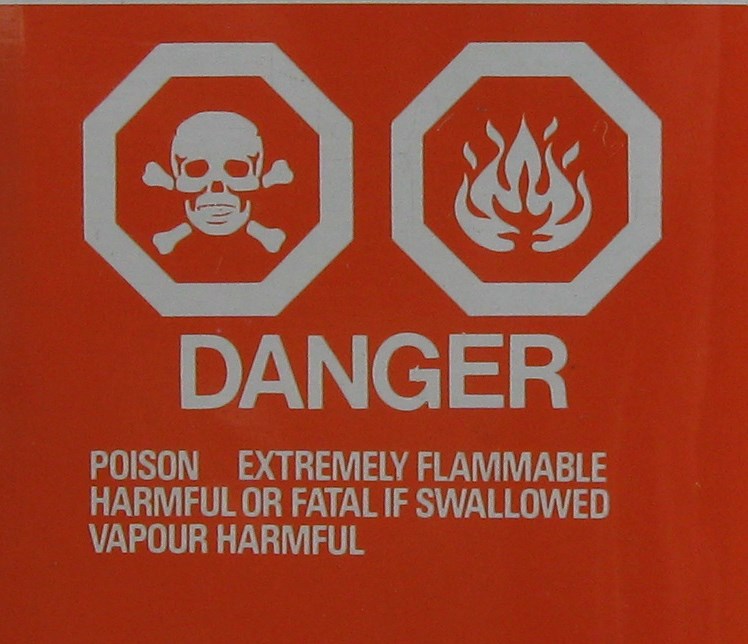

Although I’d heard the term virus, I had only a vague idea what was involved. In my mind I lumped viruses together with bacteria. I’d guessed it was a Latin word, but I didn’t know what it meant to ancient Romans. It turns out that “virus” was their word for poison, specifically the poison from plants or snakes. In English, virus continued to be associated with poison and poisonous matter for centuries. But in the late 1800s, scientists discovered that particles much smaller than bacteria – which they named viruses – could be linked to contagious diseases such as rabies and foot-and-mouth. This was only the start of the research.

Further work on the virus in the 1900s revealed that its behaviour is parasitic – it enters a living cell (called host once it’s infected) and starts replicating, for which it needs the components of the host cell. Because viruses are different from bacteria, they can’t be treated with antibiotics. Our ammunition against viruses is antiviral medication or vaccine.

From the word virus English formed the adjective virulent, which back in the 1400s described a poisoned wound. Since the 1600s, virulent has also been used figuratively to mean violent, and that’s the sense of the word in the title of my column.

These are violent times. The coronavirus is gathering momentum in its march through some parts of the world, like a poison that spreads uncontrollably. And violence, or virulence, is increasingly evident in our attitudes and actions. It’s not only south of the border where the violence and unrest are raging, fomented by the political situation. Also locally, episodes of violence, most often involving racism, seem to be on the rise, to judge by what I hear and read in the media.

We’re definitely becoming more aware of social violence thanks to the exposure it’s getting. Exposure is an effective weapon to deploy in battle, as we can see clearly when it comes to the fight to eliminate other poisons. Currently, in Richmond, several conscientious citizens are ready to wage war on the second-generation anticoagulant rodenticide (SGAR) used in bait-stations distributed throughout the city. This type of poison doesn’t kill the rodent immediately. Death occurs between four to 14 days after the rodenticide is ingested. In the meantime, other animals – wildlife as well as pets – can themselves become poisoned if they eat a poisoned rodent. Furthermore, the substance can poison our land and waterways.

Scientists are furiously searching for ways to save humans from the virulent coronavirus. As for the other virulence and poisons in our lives – the social as well as environmental issues – we ordinary folk can surely conquer them by way of extraordinary measures of dedication, compassion, and humaneness.

Sabine Eiche is a local writer and art historian with a PhD from Princeton University. She is passionately involved in preserving the environment and protecting nature. Her columns deal with a broad range of topics and often include the history (etymology) of words in order to shed extra light on the subject.