Your great-great-great-grandparents and Santa Claus may have been in touch by letter. However, if you imagine those letters were lists of toys he was requested to leave under the Christmas tree, you’d be wrong. For much of the 19th century, Santa Claus didn’t get letters from children, he got letters from parents telling him if their children had been naughty or nice. Santa would respond accordingly. Thomas Nast’s illustration in Harper’s Weekly magazine of 1871 shows Santa at his desk, confronted with stacks of letters. One stack was from parents of naughty children and it was several feet high. The other stack could be measured in inches.

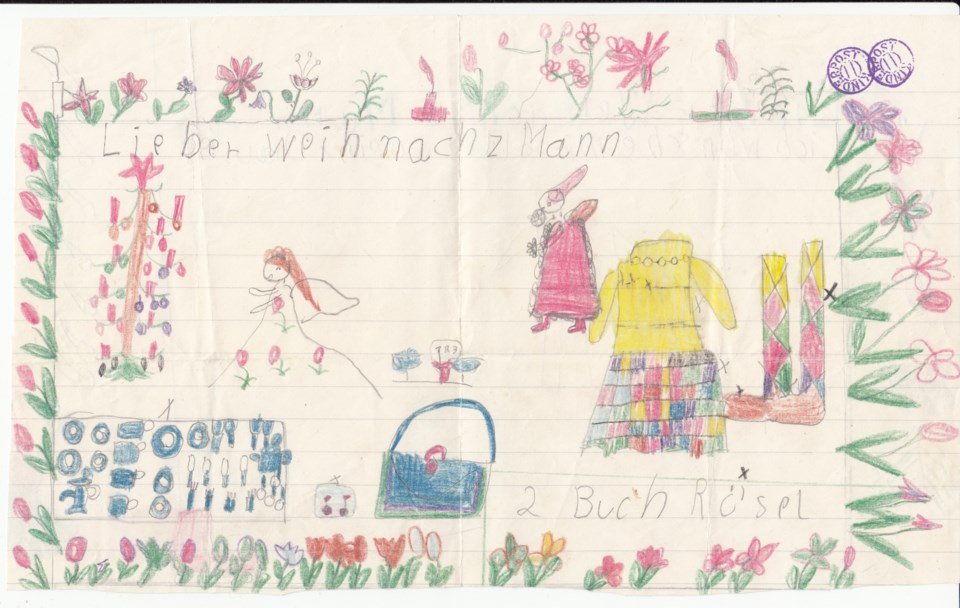

Soon Santa stopped being a disciplinarian and started to deliver gifts. Children wrote to let him know their heart’s desire. It took a while before they entrusted their letters to the post office, and children devised ingenious ways to get their message to Santa. One was to leave letters in the fireplace, confident that when they burned the smoke would carry their wish lists to the North Pole where Santa lived.

When I learned of the smoke-carrying stratagem I initially wondered how this could be reconciled with Santa coming down the chimney to leave presents, but then I realized that the fire would be out by the time he made his descent. Santa using the chimney to enter the home was first mentioned by Washington Irving in his 1809 History of New York. However, it was Clement Clarke Moore who immortalized Santa’s arrival via the chimney in his poem “’Twas the night before Christmas”, published anonymously on December 23, 1823, in the Sentinel, the local newspaper of Troy, New York (the poem is also the source of Santa’s eight reindeer and their names).

The tradition of children sending their letters to Santa through the mail seems to have been well underway in the U.S. by the late 19th century. It brought unforeseen problems. What do you do with letters for a fictitious addressee at an imagined location? The usual way to deal with undeliverable mail was to send it to the Dead Letter Office (DLO).

Some post office employees took matters into their own hands, opening the letters (strictly against the rules) and fulfilling the children’s wishes or collecting money to give to needy children. In 1907 the rules changed and the Postmaster General allowed letters to Santa to be forwarded to charitable institutions or individuals for philanthropic purposes, but because of irregularities, the policy was revoked the following year. It was reinstated in 1911 as Operation Santa Claus (also referred to as Letters to Santa or Operation Santa), which was formalized in 2006.

Inevitably there were fraudsters along the way, ready to step in and help themselves. Probably the most notorious of these was John Gluck, a customs broker in New York City who launched the Santa Claus Association in 1913 and served as an intermediary between the donors and needy children. Fourteen years later it was revealed Gluck had embezzled most of the donations intended for charitable work. He was never charged with the crime but retired to Miami where he became a real estate agent.

Canada Post, like its U.S. equivalent, was receiving letters to Santa by the early 20th century. They’d be answered by postal workers. In 1982 Canada Post established the Santa Mail programme, recruiting volunteers to respond to the letters sent to Santa Claus, c/o North Pole, H0H 0H0 Canada. (As an aside, Santa Claus holds Canadian citizenship, awarded to him by Jason Kenney, Minister of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism on December 23, 2008.)

Children now have a choice of ways to get their letters to Santa, who has become as tech-savvy as the kids. Some still compose their letters on paper and send them through the mail. At the Santa Claus museum, in Santa Claus, Indiana, volunteers write replies but they’re asked to use block letters because at this point most children are unable to read cursive.

Sabine Eiche is a local writer and art historian with a PhD from Princeton University. Her passions are writing for children and protecting nature. Her columns deal with a broad range of topics and often include etymology in order to shed extra light on the subject.

Got an opinion on this story or any others in Richmond? Send us a letter or email your thoughts or story tips to [email protected]. To stay updated on Richmond news, sign up for our daily headline newsletter. Words missing in article? Your adblocker might be preventing hyperlinked text from appearing.