Richmondites will have one more option to find out if they have hepatitis C starting Monday as London Drugs joins other community organizations offering testing for the curable liver-targeting virus.

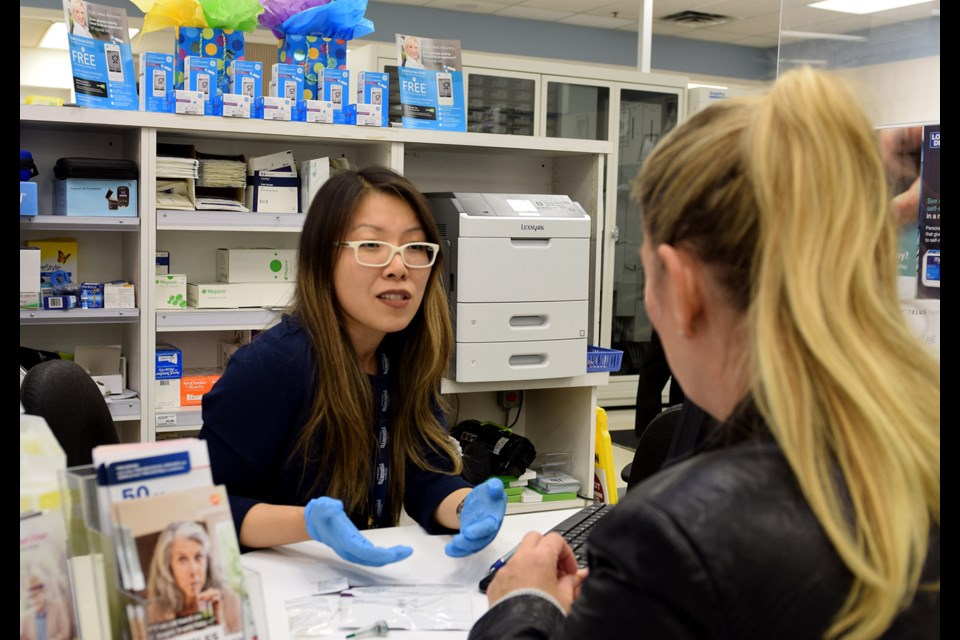

London Drugs rolled out in-pharmacy hepatitis C testing at some of its Lower Mainland locations earlier this fall, and on Nov. 19 will begin offering it at its Ironwood location.

“We want to provide a convenient way for people to access care,” said Jane Xia, manager of special pharmacy services.

The test involves a quick finger-prick, and 20 minutes later the pharmacist can read the patient their results and connect them with a physician if it looks like they’re producing hepatitis C antibodies.

Hepatitis C is a virus that targets the liver, and there is no vaccine for it (unlike hepatitis A and B). If left untreated, it can cause liver damage and even liver failure. The province estimates 73,000 people in B.C. are living with the virus, and one in four don’t know they have it.

But the good news is there’s effective treatment available. In March, B.C. followed Ontario to extend public coverage of hepatitis C medication to anyone diagnosed with the virus. Previously, people who didn’t have drug plans would have had to pay $45,000-$50,000 for a round of treatment. The province would fund it in certain cases, but only if there was advanced liver damage.

At London Drugs the tests cost $24, a fee which covers the testing kit itself, Xia said.

The pharmacy is the latest option available for getting tested for hepatitis C, but community organizations around the Lower Mainland have been pushing to get baby boomers and people from immigrant communities tested since the beginning of the year, with grants from Gilead and the Public Health Agency of Canada.

They’re paying particular attention to people in immigrant communities, since hepatitis C is considered endemic (greater than two per cent prevalence) in much of the world outside North America, and people may immigrate to Canada without knowing they have the virus.

Gigi Lo, with SUCCESS Richmond, heads the language and settlement organization’s hepatitis C testing program.

"“We do find that it still carries a bit of stigma,” Lo said. But after listening to education seminars on the virus, she says students become more open and receptive to getting tested.

On Oct. 26, public health workers set up a testing station outside a SUCCESS language class, and students lined up to get the inside of their cheeks swabbed for signs of hepatitis C and HIV antibodies.

Yi Wang and his wife JianHua Wang both got tested.

"Why get tested? Because it's safe and convenient," Yi said.

The tests through the SUCCESS outreach program are free of charge, and a physician on-site can connect people with care should they test positive.

One 23-year-old who got treated for hepatitis C last year is urging others to know their status, since now it’s fairly easy to get cured.

“It’s just so important to be, like, proactive with your own health,” said Kamal G., who didn’t want her full name used to keep her medical history private.

She was diagnosed with the virus when she was 12 years old, but didn’t get treated sooner because she was young and her liver appeared healthy.

She isn’t sure how she got it, but once she tested positive, her mother was also tested and found she had the virus. She knows her dad received a blood transfusion in India, and wonders if improperly sterilized equipment could have exposed him to the virus.

Kamal lives in Surrey and graduated with a BSc. from UBC earlier this year, and wants people to know that having the virus hasn’t kept her from achieving her goals. Although, now that it’s been cleared from her system, she says it’s a “psychological relief” to know that it won’t get worse.