Living under the No. 2 Road Bridge. A makeshift home in a stairwell off No. 3 Road. Birth certificates and other documents stolen or ruined by the weather. Hands and toes freezing. Couch surfing. Sleeping in abandoned vehicles.

Survival

Four residents of the 40-unit Temporary Modular Home (TMH) in Richmond, which opened April 23, recounted their experiences of living on Richmond streets before getting a 300-square-foot home in a safe building with built-in support to help them get their lives back on track.

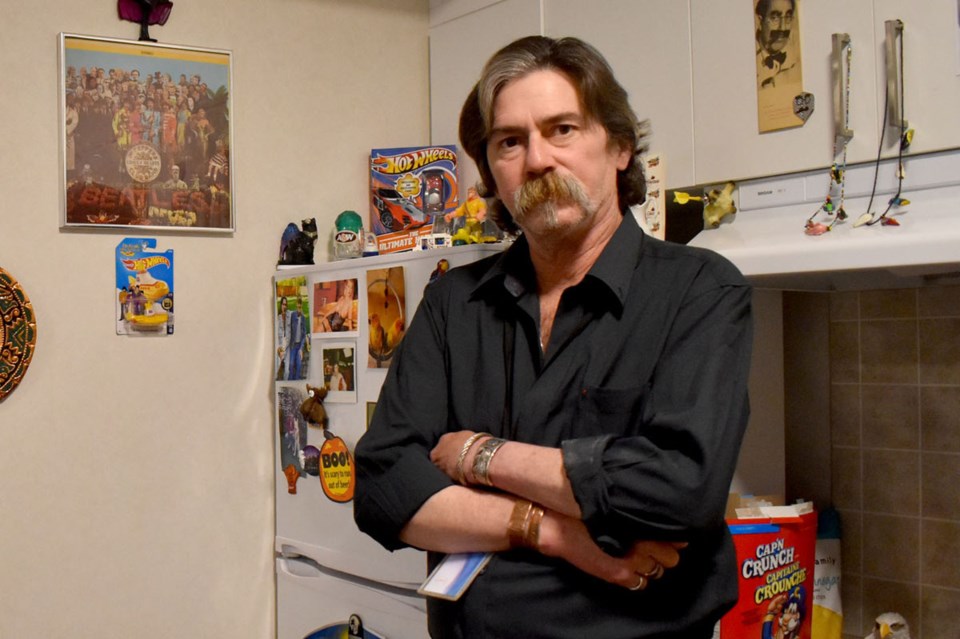

Richard Miller moved in on the first day the TMH opened, coming straight from the hospital where he was being treated for pneumonia. In his late fifties, after living in Richmond for a couple decades, he ended up homeless, and he took to staying in men’s shelters, at Richmond House and the South Arm Community Centre, as well as on the streets.

Now, at the age of 62, he has a warm room, a roof over his head, a bed, a bathroom and a place to keep his belongings.

“It was a huge relief,” he said. “I was so depressed. I had lost my whole family — I had no one to turn to.”

Miller lost his wife 10 years ago, and then a few years ago, his mother and brother both died within a close period of time. He also lost most of his possessions, including 18,000 vinyl records from his DJing days at Fantasy Gardens in Richmond and the clubs of Vancouver.

Miller is aware of the criticism and scrutiny the building is getting from some people in the community, but he challenges these critics to “come sit down and talk with us before you judge.”

“Don’t try and take the only things we have away from us,” he said. The people in the building are warm and they have food, he added. “Do you want to send us back to the streets?”

The building was approved by Richmond city council last year after two contentious meetings where some local residents vociferously opposed its construction, saying it would lead to drug addicts and people with mental health issues posing a safety risk to residents.

Many spoke, though, at the council meetings in favour of the TMH.

There was a formal group opposing it, called “7300 Group” (referring to the original street address).

Ivan Pak, who was a vocal critic of the TMH, said he is still concerned the building will attract criminals, and he receives almost daily emails from people living next to the building who are monitoring what’s going on there.

Pak said he’s not conerned about the residents doing anything criminal, rather, that the building will attract criminals to the area.

“If we have drug users in the temporary modular housing, they will attract drug dealers to that neighbourhood,” Pak said. He added that “if they need some drugs, they need to find some way not to do it in the neighbourhood.”

Some issues Pak has heard about include shopping carts that weren’t “immediately” removed and needles found in a nearby stairwell and at Brighouse Park — this can have an impact on the image of the area which includes several hotels with tourists, he said.

But instead of just complaining, Pak said he wants to keep working with RainCity and the neighbours to address the issues. He sits on the TMH advisory committee.

Since opening, several concerns have been brought to the city’s attention about the TMH from a few individuals living close by about, for example, shopping carts and loitering.

“In all those cases, we and the RCMP (…) have not found any cause for concern,” said Clay Adams, city spokesperson.

One day, a concerned neighbour took photos of what seemed to be a drug deal close to the TMH, but when the police investigated, there was no evidence of a drug deal, he added.

The RCMP have been monitoring a 500-metre periphery of the building and there has been no significant impact to violent crime, traffic offences, property crime or any other occurence types.

City bylaws say there have been no bylaw violations associated with the building.

With no other family around, Miller said he’s found his new family at the building run by RainCity Housing.

Miller already knew several of the residents coming into the building, and he has gotten to know the support workers in the building who are “fantastic,” he said.

“You can’t ask for better staff,” he added.

A year without a home

David, who moved to Richmond in 1997, carried his guitar and backpack wherever he went after losing his home a year ago. Before that, his housing situation varied — sometimes, he rented with friends or stayed in shared accommodations.

But in the last year, he struggled to find any place to live and ended sleeping in parkades and stairwells.

“There was no room at any of the inns,” he said. “Being homeless for that year, I had no idea what I would do.”

At some point, his home was under the No. 2 Road Bridge where the “bike cops” would come to check on him and fellow campers to make sure they were okay. Once, someone lit their camp on fire.

David moved into the Richmond TMH in May, and he described the building as “fantastic.”

“We have the opportunity to carry on and rebuild our lives,” he said.

By May 5, the building at the corner of Elmbridge and Alderbridge was full with 15 women and 25 men, all from the streets of Richmond.

The mission statement of RainCity Housing is “a home for every person,” which building manager Adina Edwards said might sound trite. But the deeper meaning of a “home” is having a shared community with food, health care, engagement and support and this is what RainCity aims to give all the residents at the Richmond TMH.

“They’re not individuals who just need affordable housing,” she said. “They need 24-hour support, for mental health, for safety around substance use and physical health concerns — and their vulnerability.”

RainCity’s service model is “bio-psycho-social,” Edwards explained. Bio is health, psycho is mental health and social is community — all three have to come together in order for people to thrive.

There are at least two staff at the building at all times, residents get two meals a day and there is programming and support.

Five years on the street

Sophie spent five years on the streets of Richmond before moving into the TMH building. The streets can be much more dangerous for women than for men, she said, and being without shelter can be draining.

Homeless people are constantly cold, their hands and feet are freezing, they’re always hungry and they never get a comfortable night’s sleep, Sophie explained. There is no safe place to keep their belongings or their important documents, like a birth certificate, papers needed to access many services.

“You’d constantly have to carry your things — if you go anywhere, it’s exhausting,” she said.

Sometimes Sophie would sleep in an abandoned car, sometimes in a small camp. She ended up in the Vancity stairwell off No. 3 Road where she got to know others living on the street.

Last winter, Sophie, who is 52, started going to shelters downtown because she was feeling so much weaker.

“I wasn’t sure if I was going to make it through the winter,” she said.

Support in addictions

The TMH is a low-barrier shelter and many of its residents have addictions. RainCity provides harm reduction services and support to minimize their risk of overdosing, Edwards explained, but there is no drop-in space for drug consumption — their agreement with the city states this is not permitted.

For addicts, there is a lot of shame and stigma surrounding their substance use, which is why many people use alone and die from overdoses, Edwards explained.

The assumption by opponents to low-barrier shelters is that if a building allows people to use illicit drugs, they’re facilitating it, something Edwards refuted.

“The idea is we’re here for people when they’re ready to make changes,” she said. “Addiction isn’t always a linear process of using, getting clean and sober and staying clean and sober.”

The clients of RainCity have mental-health issues that make their addiction more cyclical, she added, and they might have periods of sobriety, but it’s not a direct, linear path.

Danielle, who has moved into the TMH, accepts responsibility for her drug addiction, saying no one forced her to do drugs. But, at some point, addicts just need some help getting out of their cycle of addiction, she said.

Before moving in, she was living in the same Vancity stairwell on No. 3 Road that Sophie frequented. The encampment started with three people, Danielle explained, and eventually grew to about a dozen. The security guard would make sure they were gone at 7 a.m., and someone would come and clean up after them after they left. They could come back at 6 p.m.

Danielle said when she tried to find housing, prospective landlords just looked her up and down and refused to take her in, making her feel like an outcast.

“Everyone treats you like shit,” she said.

The non-judgmental staff at the TMH and their support is giving her hope for the future. She wants to go back to school and work, to reconnect with her kids and eventually get her own home. The TMH is helping her get back on her feet, she said.

“It’s getting me back on track,” she said. “It’s opening my eyes that there’s more help out there than I thought.”

Danielle and Sophie list the people who have helped them throughout their years on the street — Morgan, Hugh, Diane and Nancy are the names they remember.

Edwards said RainCity staff are grateful for the support they are getting from the community in Richmond as they get the TMH off the ground.

“Richmond has an amazing amount of outreach workers, clinicians and mental health workers, and they have really embraced and welcomed us into the community,” Edwards said.

And these community workers are grateful for the housing that their mutual clients finally have, to give them stability to come to appointments and receive the help they need, she added.

RainCity is also developing a “great working relationship” with the RCMP, the fire department, BC Ambulance Service, the city’s bylaw department and the Poverty Action Committee, Edwards said, agencies and departments that already have been working with the homeless population for years.