At the train station, the teenagers kissed and held one another. She told him she loved him. He told her he loved her. Their hands parted and he stepped on the train. She would watch it depart into the distance and find her way back home to Richmond on the interurban tram. It was the last time they saw each other.

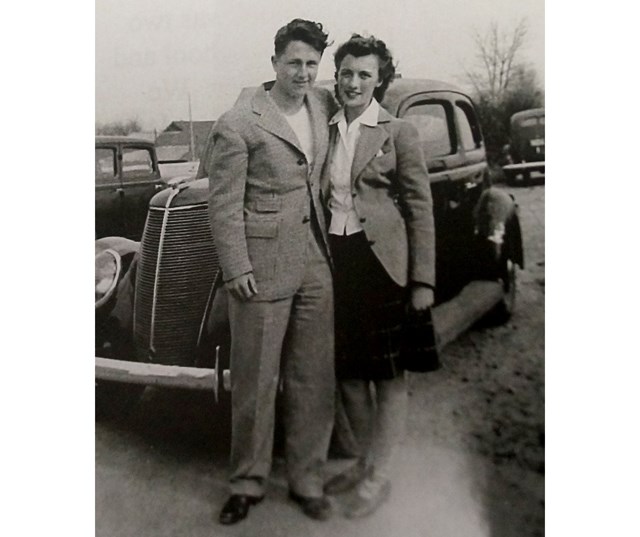

Weeks earlier, in the spring of 1943, Pte. Bob Bowcock had put a ring with the “littlest, most beautiful diamond” on the finger of his first love, Irene Wagner.

“He had said, ‘When I go, you go out with other guys.’ I said ‘What guys?’” recalled Irene Wagner Stiles, with a wry smile.

“You know, there was nobody around during the (Second World War). Anyhow there wasn’t any way I was going to do that anyway,” said Stiles, from her home in Richmond, where she’s lived most of her life.

Stiles read the story of her first love in the Richmond News on Friday and contacted the newsroom to talk about her “great guy.”

For Stiles, at age 90, Bowcock is a love lost, but not forgotten.

Stiles married after the Second World War, to another man who would become her greatest love — Sonny Stiles, another soldier whom she would spend 55 years with and raise five children.

But the loss of Bowcock is a moment that Stiles will never forget. The love they had for one another is eternally lost in a parallel life that she would never know.

“You can’t forget your first love,” she said.

Bowcock and Stiles grew up together in the north Richmond neighbourhood of Eburne. His mom operated a grocery store, her parents owned a 10-acre farm.

“We were a community unto our own, there was no transportation except for the tram, two or three miles away, so we did everything on bikes. We’d go to the river for picnics, that sort of thing,” said Stiles.

And so, as teenagers, they and others hung out with one another. Stiles recalled falling in love with Bowcock at age 13, but “he never noticed me until I was 17. Until then, we were just a big group of friends.”

The two became boyfriend and girlfriend for a short period before Bowcock left to join the Canadian Scottish Regiment in France, where he would die on July 8, 1944, during the invasion of Normandy.

“He was very patriotic. He thought it was his job to go over. The boys didn’t do it for any other reason other than patriotism. No other reason. He was a good guy. He had high morals, worried about other people. He was a really good person. I just can’t say enough about him at this time. He was mature beyond his years and very smart, very clever,” said Stiles.

Bowcock initially insisted the two were too young to get hitched. Stiles was “heartbroken,” as she would later describe that moment in her journal.

“But as time got short, his thinking changed, and I’ll never forget the trip into town on the interurban to a movie when he put a ring with the littlest, most beautiful diamond on my finger. I was on Cloud Nine,” wrote Stiles of their last date together in the spring of 1943.

She said her parents questioned the two and the engagement caused “a big kerfuffle” at school.

But the heart wants what the heart wants.

And so, they spent the last remaining days together, before Bowcock left school early to attend training in the Interior.

Stiles became an impassioned letter writer and Bowcock wrote back. Such was the reality of the day.

“There were no boys, we didn’t date. We wrote letters. It was just the way things were. Everyone was in the same situation; the boys were gone, and the girls were left,” said Stiles.

Her parents were immigrants from Germany with farming experience. In 1933, the Wagners moved from Saskatchewan to Richmond, which offered more prosperous farming opportunities.

She helped on the farm, as most women did, but also used her writing skills to land a job — paying $100 per month — with the income tax office in south Vancouver.

“When I was working, every day I bought a newspaper to see the column of people who were killed in the war the day before. There was, quite often, someone I knew,” she said.

Stiles said she put a map of Europe on her wall and placed pins to denote where Canadian soldiers were fighting.

By Christmas time in 1943, she knew Bowcock was on his way to Europe. She said he had become a lance corporal, meaning he was a higher-ranked private. The moniker was lost after the war so records don’t show how Bowcock was a young leader amongst his battalion.

As the conversation progressed toward D-Day, Stiles held back tears.

“I know he was deployed at Christmas because I had knit him a sweater. Later on, I didn’t get too many letters once he got to France, but one of them said he had lost his sweater and he was feeling really bad about that. I guess he lost his pack or something. And before he left, I had bought him a watch — he didn’t have a watch. I don’t know what I paid for it, but after he died, I was still paying for that watch for six months.

“I thought, ‘whatever happened to that watch?’ It never came back. So, it’s hard to know just how bad it was, because they didn’t get mail and they didn’t send mail from where they were. He didn’t go in with the first wave. But soon after,” said Stiles.

Sitting in her living room chair, Stiles took a moment to reflect with her eyes down. She then raised her head.

“I’ve learned a lot since then about how many people got killed in that first wave. It’s astronomical. The Canadians, you know, Canada is a small country compared to others. Oh my God. It was awful. I mourn him to this day,” she said.

On July 8, 1944, the day Bowcock was shot by Nazis, Stiles was visiting friends in Calgary.

“Something came over me, I don’t know what,” explained Stiles.

She wrote in her journal: “It was like a black cloud came down in an instant. I began crying for no apparent reason.”

Days later, a non-descript telegram would be sent to Bowcock’s mother, who shared the news with Stiles, who subsequently fell into a depression.

“I was sure my life was over. I roamed the bog for hours in solitude, my tears pouring down my cheeks, looking for answers,” she wrote.

Stiles said she found solace with friends and attended the Hostess Club, where they had dances.

It was there where two soldiers approached her with details of Bowcock’s death.

“The two men came into the frat hall, said they were buddies of Bob and with him when he died. They were telling me that they felt he had sacrificed his life for theirs. I thought that would be like him,” she said.

It wasn’t until the 60th anniversary of D-Day that Stiles said she truly, properly mourned Bowcock.

She’s truly thankful for the moments Bowcock gave her and the freedom he gained for her to raise a family.

“On the 11th I walk over to the cenotaph. I look at all those names and I know most of them. They were all like us.”