For most people, Remembrance Day is a time reserved for honouring those who fought in the war, both alive and dead.

Many ceremonies are held across the country, where people visit memorials, nameplates, or tombstones acknowledging those who served.

But what if these places of recognition don't exist?

It can be hard to remember when there is nothing to mark or recognize a fallen soldier.

A Grade 12 history class at J.N. Burnett secondary decided to right this wrong, fundraising for the more than 900 unmarked soldiers' graves at Vancouver's Mountainview Cemetery.

"I was really shocked to find out there were so many unmarked graves, and quite saddened," said history teacher Patrick Anderson. "We talk about Remembrance Day, and we go through all the right motions, but I'd say most people don't know or think about this fact."

Anderson had heard about teachers in the U.S. fundraising to buy grave markers for soldiers whose families may not have been able to afford the cost at the time. He wondered if the same applied to a local cemetery.

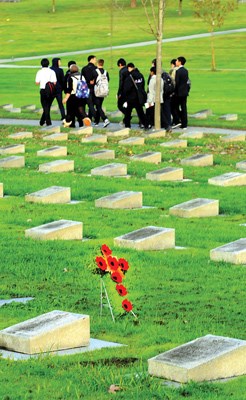

After presenting the idea to his class, the group of about 20 students dressed in somber colours and visited the cemetery Wednesday afternoon to see where the unrecognized are buried in the Field of Honour.

"When he first told us about it, I was, like, 'Oh, that's going to be more work for us,'" joked student Jeremy Hudson. "But being here, it's really kind of interesting. It's cool to know we're going beyond history, like contributing to history in the present."

The cemetery tour, guided by volunteer John Atkin, kick started their fund raising efforts, where in the coming weeks they'll canvas around the school and possible places in the community, hoping to raise close to $1,000, as each plaque costs $225.

"We're trying to do something outside of the classroom here," said Anderson, who's been at the school for about eight years and teaching history for close to five. "It's learning history by doing. We want to emphasize social responsibility in schools now, and this is a real chance to do something."

Throughout the tour, the students maintained a respectful composure, asking Atkin questions. Some talked amongst themselves about the experience as they walked from section to section, while others silently took it in.

"It's a great idea, I've never heard of students doing something like this," said student Shannon Weatherill, whose grandfather served in the army.

"It's a legacy for History 12, that we're part of something bigger than just listening in a classroom. I wasn't surprised that unmarked graves exist, but surprised that there are so many here."

There are about 12,000 veterans buried in the cemetery, mainly divided into two sections - the Commonwealth War Graves (for those who died in action) and the Field of Honour.

As the group approached these sections, the rows and rows of tombstones seemed more concentrated, more populated, while simultaneously, a vast expanse of grass indicated the amount of unmarked dead.

"It was a little bit overwhelming to see all these veterans," said Michael Yamaguchi, another student in the class.

The project highlights the importance of identity and acknowledging that someone lived and contributed to the history of the nation, regardless of the fact that families or friends of these veterans may not be around to see the plaque.

Similar to an official government apology, where the present parties didn't commit the wrong, Anderson still feels it is an important wrong to be righted.

"It may be that nobody will ever look at these plaques, but I think it's the right thing to do. I'd definitely come back in the future to visit. These people have made this great sacrifice, but there's not enough for them after the war. On a basic level, it's not right."

The cemetery fundraises separately for unmarked graves through its Veterans Memorial Project where people can donate online. Through cemetery records, it is able to identify where the soldiers have been buried.