Fifty years ago half of all Canadians over age 15 smoked. Laws restricting smoking were virtually non-existent, and tobacco smoke seemed to be everywhere.

Air was thick with smoke in Richmond’s indoor spaces — from school staff rooms and city hall to restaurants and shopping malls. Cigarettes were widely available, even from vending machines. But change was coming. Richmond council made sure of that with a historic bylaw 30 years ago.

On April 14, 1986, council adopted Bylaw 4514, the first local law that targeted smoking. The issue had long been on council’s radar, as talks about restricting smoking in public areas began a decade earlier, according to city hall records.

Coun. Harold Steves, Richmond’s longest serving council member, said Richmond was one of the first jurisdictions to target smokers.

“It was unbelievable actually having clean air to breathe when we banned smoking at council meetings, then public buildings and schools,” said Steves.

Bylaw 4514 created sweeping change. It wasn’t without its critics. But perhaps the most vocal resident, Norman Wrigglesworth, was a supporter. Stormin’ Norman, as he was known by some for his colourful council presentations, started campaigning against smoking in the 1970s. The late Richmond resident urged council to introduce a ban in public areas, much like Ottawa did in the late-1970s. He watched with impatience as Toronto, then other municipalities, followed suit.

“P.S. The real Prince Charles hates smoke,” he wrote below one of his letters to council at the time.

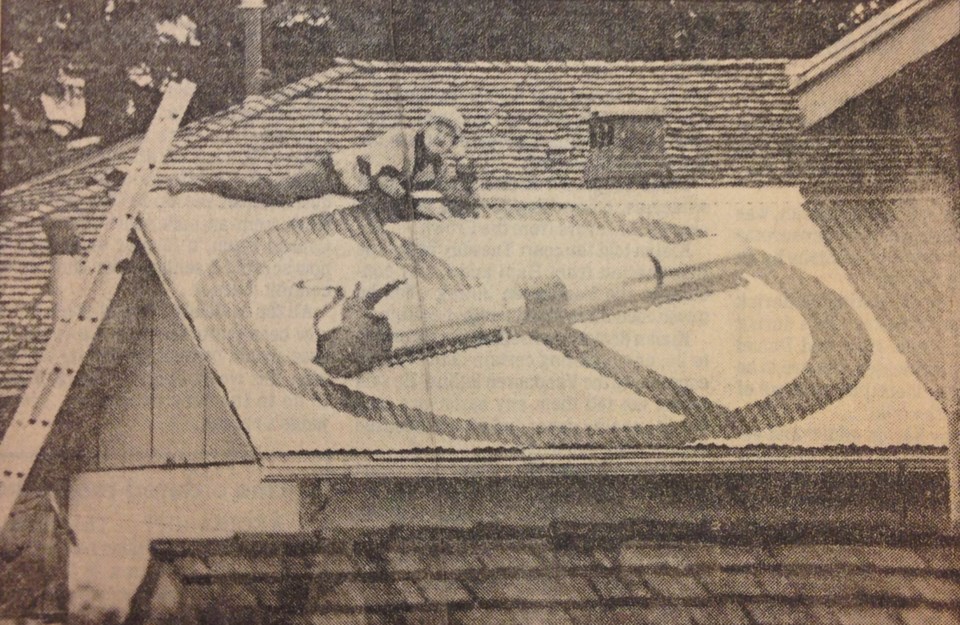

In 1983 Wrigglesworth built a four-metre-square no-smoking sign on the roof of his Richmond garage. Three years later, a bylaw was in place.

Richmond’s new rules banned smoking in retail stores, service counters, government offices, hospitals and health clinics. Smoking was still allowed, however, in designated areas.

Restaurant owners were also required to act, but they were granted leniency. A sign was required at the entrance of every restaurant indicating whether non-smoking seats were available inside. But whether a smoke-free section was available was entirely up to the owner.

Council’s bylaw also banned smoking in elevators, escalators and stairwells, public buses and taxicabs — unless the driver and passengers were OK with second-hand smoke.

Elected officials set the maximum penalty for an operator at $500, while individuals caught breaking the rules faced a fine between $25 and $500.

The bylaw also ensured the no-smoking sign would become ubiquitous. Multiple conspicuous signs were mandatory everywhere smoking was banned.

One year later, in 1987, council introduced a second set of restrictions aimed at workplace smoking. Bylaw 4762 was intended to “severely limit smoking in the workplace other than under certain conditions,” noted the municipal clerk of the day, Rod Drennan. Workplaces could still have smoking areas, as long as non-smokers didn’t need access to such areas.

Coun. Steves said it was because of serving on council — in smoke-filled chambers before the bylaws were introduced — that he developed asthma.

“When I was first elected everyone smoked but me. The planning committee room in the old city hall was an inner room with two doors and no windows,” he remembered. “When the meeting began everyone else lit up a cigarette and (alderman) Bob McMath a cigar. I watched the smoke curl up to the ceiling.”

Steves also remembered his second election campaign, and trying to deliver a speech with tears running down his face while other candidates puffed away.

“Eventually, my breathing got bad and I had difficulty breathing outdoors on days there was heavy particulate in the air,” he said. “I have been on puffers ever since.”

More rules to further restrict smoking would come from the city and the province. In 2002, provincial legislation required all workplaces that chose to permit smoking to create designated smoking rooms. The law went further in 2008 with a province-wide ban on smoking — and no allowances for smoking rooms.

“People still didn’t get the message and we had to ban smoking in the parks as adults would light up their cigarettes when watching their own kids playing games,” said Steves.

Whatever the cause, smoking rates have dropped substantially since Richmond first introduced a smoking bylaw in 1986, according to Statistics Canada figures. Today, just 18.1 per cent of Canadians smoke, compared to 33 per cent three decades ago.