The rate of illicit drug overdose deaths in Richmond has tripled in the first four months of 2017, over last year — the largest spike of any “health service delivery area” in the province, according to the BC Coroners Service.

“We were quite concerned of the rise last year. Now we’re way past that baseline,” said Richmond’s medical health officer Meena Dawar, of the public health emergency that is now on pace to kill close to 1,500 British Columbians this year, which would be a 50 per cent increase over the record-setting death toll in 2016.

Granted, Richmond’s death rate has been historically low and the sharp spike is more likely to yield a larger fluctuation. Regardless, Dawar said there is serious concern among health professionals, police and other public officials that Richmond has witnessed 12 deaths in 2017, up to April 30, when it saw just 11 in all of 2016. For perspective, between 2007 and 2015 there were 25 total deaths.

Dawar is now calling on the City of Richmond, Richmond School District, Richmond RCMP and other community groups to meet with her staff at Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) to once again discuss the community action plan that was drawn up last fall.

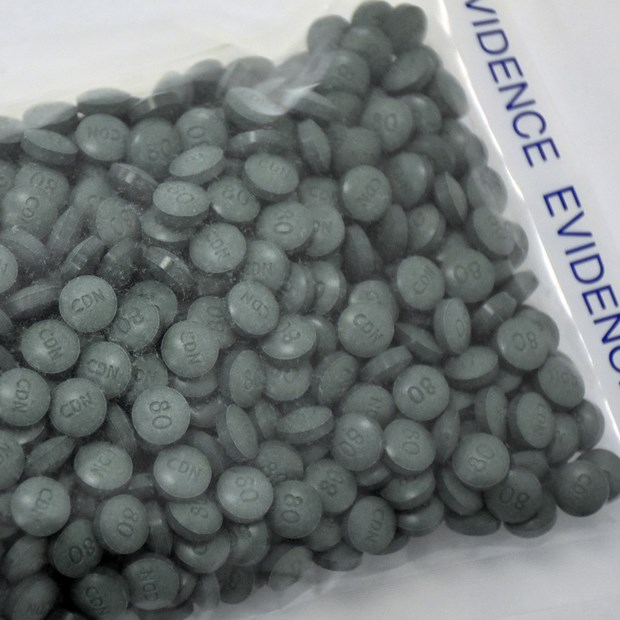

Fuelling the deaths is drugs laced with fentanyl, which is being smuggled into the region from overseas locations such as China.

“The [drug] market is so swamped with toxic material,” said Dawar.

Dawar said VCH has increased its addiction services so that there is no waiting list to access Transitions, an assessment, treatment and referral clinic for addictions. Meanwhile, the Drug and Alcohol Resource Team at Richmond Hospital is scheduled this month to open seven days a week, instead of five.

“If an individual comes in, they can be bridged to care immediately. Before, often people get lost before an appointment,” explained Dawar.

Richmond Hospital, Transitions (8100 Granville Avenue) and the Anne Vogel Clinic (8160 Cook Road) are offering free take-home naloxone kits and any help, upon request, said Dawar.

The drug naloxone is a rapid treatment for opioid overdoses.

According to the coroner, there appears to be no signs of the epidemic slowing since 2012, when there were 269 illicit drug overdose deaths in B.C.

Dawar said she could never have imagined a situation such as this. She noted during the mid-1990s a health emergency was declared in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, when provincial death tolls were about 300 per year.

She said harm reduction strategies, such as supervised-injection sites stabilized and slightly lowered deaths up to 2010.

Along with law enforcement measures and education, Dawar maintains that harm reduction strategies are working. The main problem now is the introduction of the powerful opioid fentanyl and even more powerful carfentanyl.

Noted the coroner: “Illicit fentanyl–detected deaths appear to account for the increase in illicit drug overdose deaths since 2012 as the number of illicit drug overdose deaths excluding fentanyl -detected has remained relatively stable since 2011 (average of 305 deaths per year).”

Dawar has no specific data on who is dying in Richmond, but provincial data shows victims are mostly male (83 per cent) and between the ages of 30-59 (72 per cent). Most deaths (54 per cent) occurred in private residences.

“It is of great concern that despite the harm-reduction measures now in place and the public-safety messages issued, many people are still using illicit drugs in private residences where help is not readily available,” said chief coroner Lisa Lapointe, via a news statement on May 31.