Over the past 15 years, a wave of factory trawling vessels has quietly arrived on British Columbia’s coastline, often targeting ecologically rich regions off at the edge of the continental shelf in direct competition with endangered killer whales, a multi-year investigation has found.

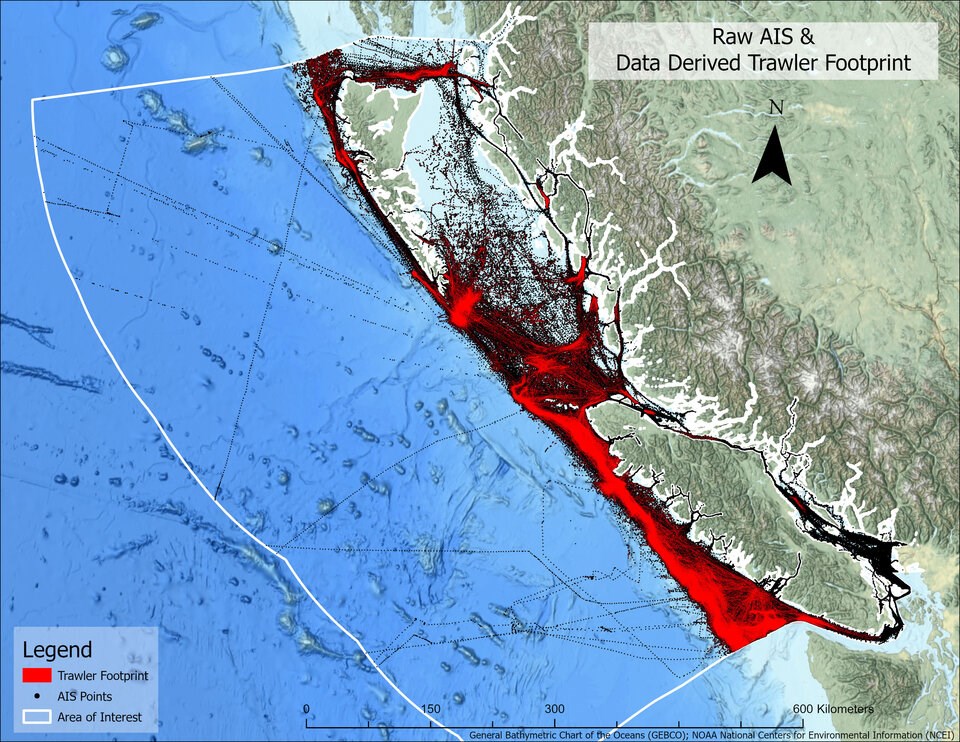

Released Tuesday, the Pacific Wild-led investigation analyzed 13 years of satellite data, information that continuously transmits a ship’s position, speed, course and identity through their Automatic Identification System.

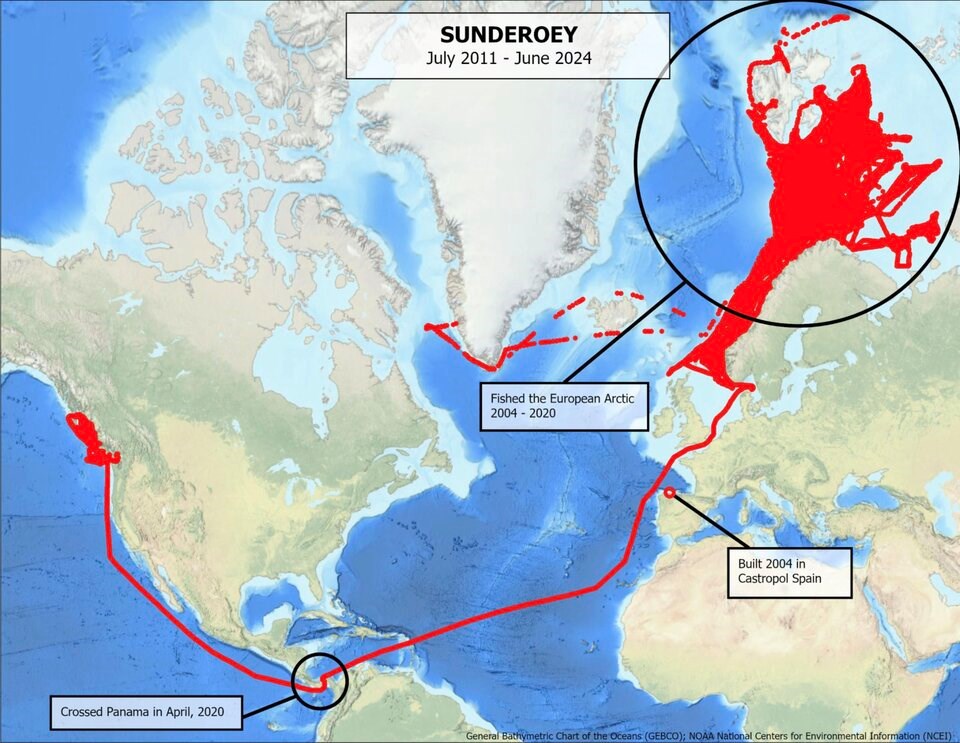

An analysis of the AIS data shows nine industrial vessels — many with checkered histories fishing now depleted stocks in the North Atlantic — travelled through the Panama Canal between 2009 and 2024. Now re-flagged as Canadian ships, the vessels have targeted a number of highly valued Pacific fish species, like pollock and hake.

Ian McAllister, a co-founder of Pacific Wild, said the arrival of the factory vessels came as the groundfish trawl fishery has undergone a transformation from largely owner-operator vessels to corporation-owned quotas.

“They just started showing up on this coast without any public input. They just started appearing here,” he said.

One of the largest fisheries by volume and value on the B.C. coast, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) gave the trawl industry quotas to land almost 300 million pounds of fish in 2024. Despite being worth more than $200 million a year, McAllister said there's little public information on how many species the trawl industry is catching, how much is being thrown overboard, and where the product is going.

Several years ago, he and his team began shadowing the vessels and documenting their bycatch — non-target fish that tend to be returned to the water, often dead. But McAllister said it wasn’t until his team got its hands on the ship tracking data that their footprint came into focus.

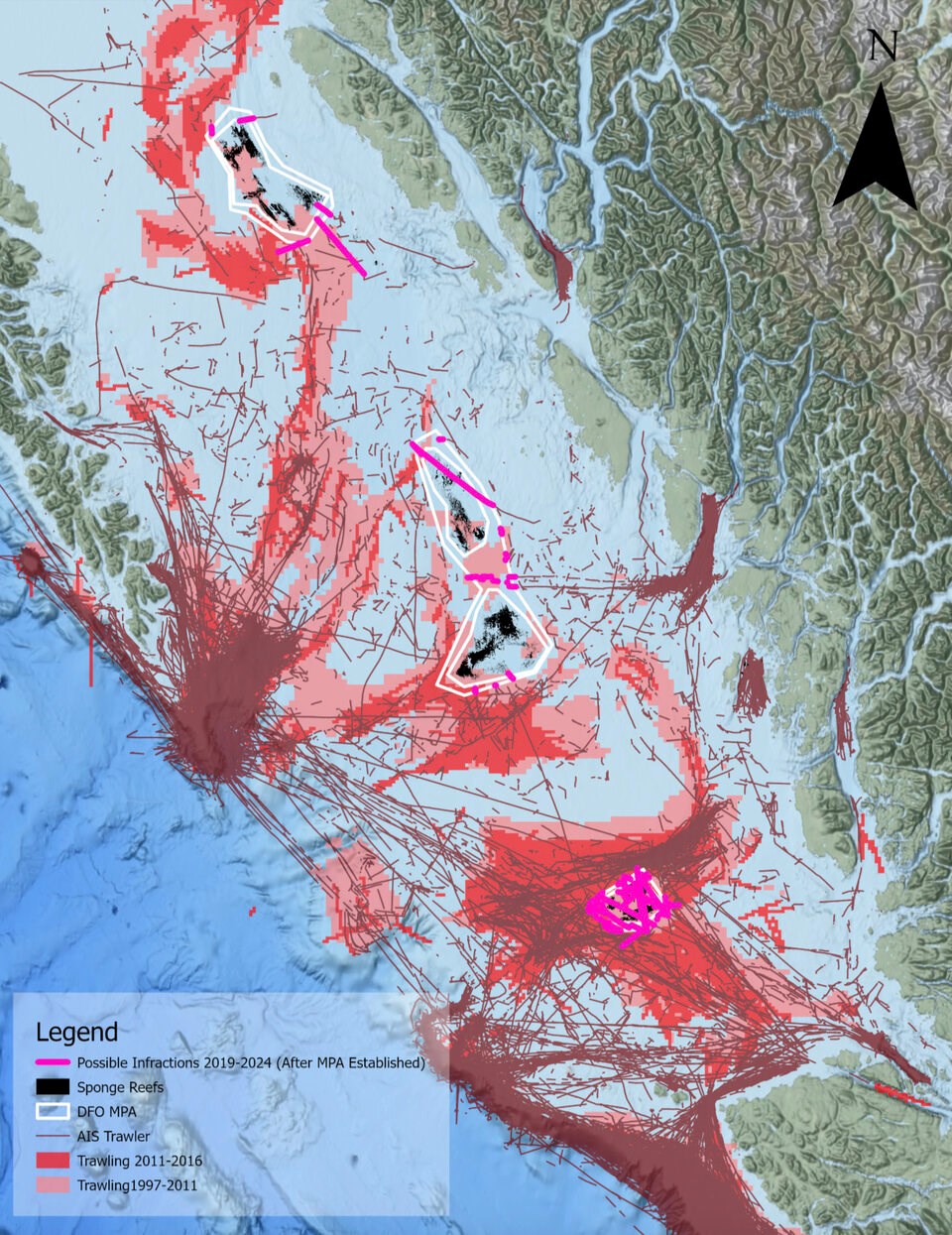

Over 13 years, AIS data analyzed by Pacific Wild shows the nine ships’ trawling activity has impacted an estimated 89,700 square kilometres of B.C.’s coastal waters — an area equivalent to the footprint of Ireland.

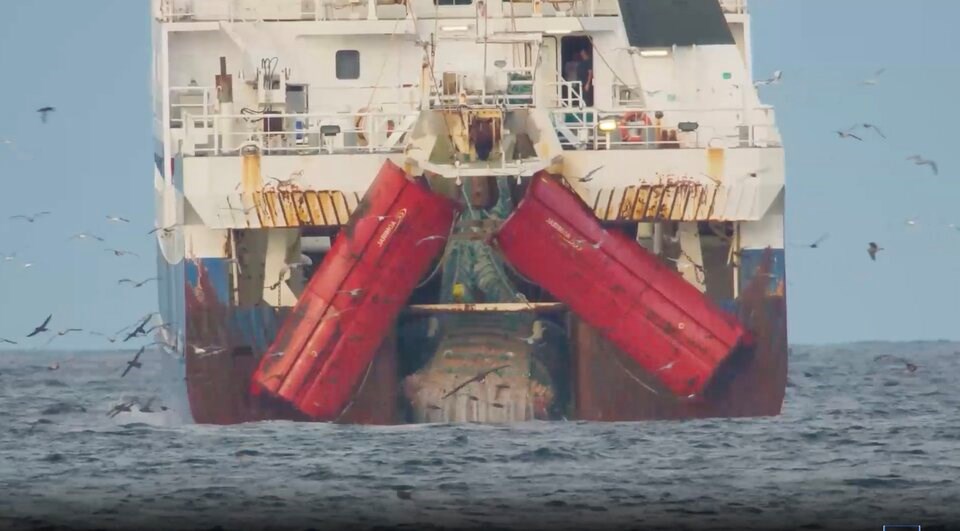

The factory trawlers have processing equipment on board that allow them to gut, cut, and flash freeze vast quantities of fish while staying at sea for weeks to months at a time.

By dragging heavy nets along the seabed, critics of the fishing technology say bottom trawling risks releasing vast stores of seafloor carbon into the atmosphere. The fishing method has also been responsible for damaging fragile ecosystems, including ancient glass sponge reefs in B.C. One 2017 study found damage to sponge reefs in the Gulf of Alaska was nearly 60 per cent higher in areas transected by bottom trawling.

Dropped through the water column, the nets often indiscriminately scoop up a number of non-target species, like the rougheye rockfish that can live up to 200 years old.

“Think about that: these fish have been swimming along the same reefs out there, hundreds of feet underwater, since before Canada was ever a country, and they're being turned into pet food and fish meal for farm salmon,” said McAllister.

“You've got a very high, ecologically valued fish species — very diverse, very old, long lived, very slow reproducing — and they're being turned into the cheapest protein commodities on planet Earth.”

Tracking data suggests killer whale prey face ‘gauntlet’ of factory trawlers

Two years ago, Pacific Wild turned to Kevin Lester, a geographic information system (GIS) expert, to see if he could find any tracking information that would show where the nine vessels had been.

After a rough start, Lester finally tracked down a largely complete data set held by a private firm that had stored the historical information. He then managed to decode the raw satellite data and plot the vessels’ travels.

Data shows the first factory trawler, Frosti, came to B.C. from Europe in 2009 after a long career in the North Atlantic. Over the next 13 years, eight more followed a path through the Panama Canal to B.C., AIS data indicates.

“We don't have information going back to the '90s or before, but that is when the cod fisheries would have collapsed in the Atlantic. And we know that a few of these trawlers were there during that time,” Lester said.

Since arriving in B.C., Lester said tracking data shows the factory trawlers have mostly been hitting fishing areas along the continental shelf about 80 kilometres offshore.

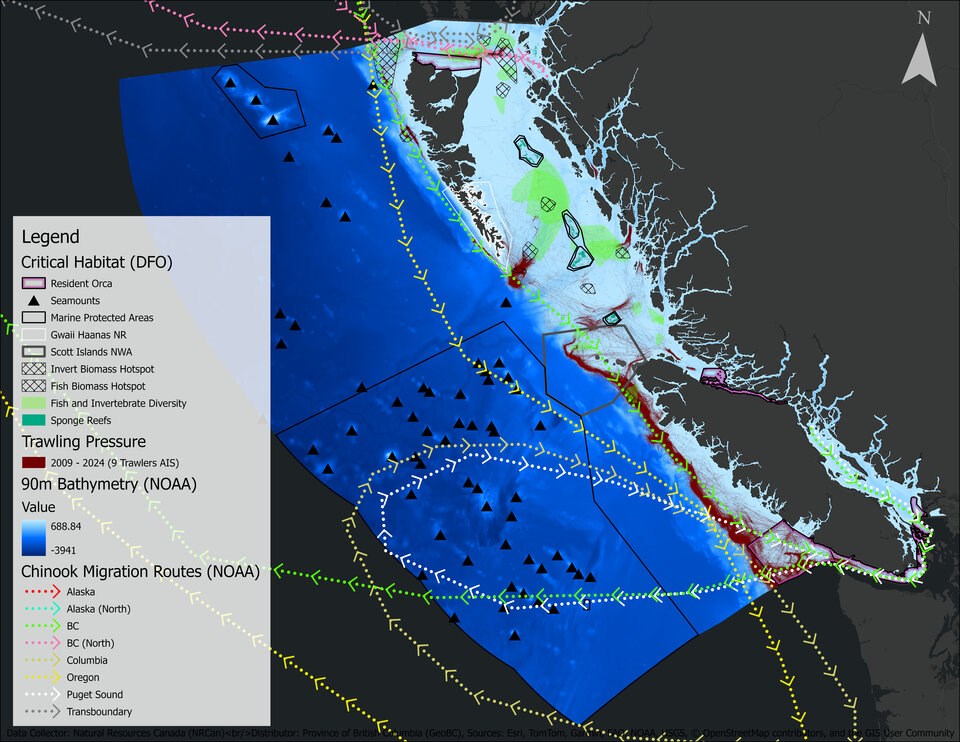

In many cases, AIS data appears to “nearly perfectly” overlap with chinook salmon migration routes — a key source of food for endangered southern resident killer whales.

One window into how much chinook is getting unintentionally caught up in trawl nets came in a 2023 report from the DFO. Results from the four-month “enhanced monitoring” program found groundfish trawlers unintentionally caught more than 28,000 salmon, almost all of them chinook. That level of bycatch is triple the previous 14-year average and higher than at any point since 2008.

The fish are part of an estimated 77,400 metric tonnes of marine life caught and discarded by the groundfish trawl industry in B.C. over the decade leading up to 2023, according to Pacific Wild.

AIS data analyzed by the group shows chinook migration routes along the continental shelf “run the gauntlet” through the most concentrated area of trawling on the coast.

Lester said the trawling activity is most concentrated in water separating southern Vancouver Island with the Olympic Peninsula. That’s the same place where northern resident killer whales and their endangered southern resident cousins get most of their food, said Lester, who has published multiple papers and mapped out killer whale feeding areas in the past.

“Their main dinner table is the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and that is heavily, heavily trawled,” said Lester.

In response to Pacific Wild's findings, Zoe Ahnert, executive manager of B.C.’s Deep Sea Trawlers Association, said bycatch, including chinook salmon, is closely monitored and DFO regularly evaluates measures to protect habitat for southern resident killer whales.

“We urge caution in interpreting raw AIS data without context or supporting fisheries science,” Ahnert said.

Factory boats regularly transited protected areas at trawling speeds

Over several years, the Pacific Wild investigation found the factory trawlers often travelled at trawling speeds over seamounts — undersea mountains that often form the bedrock for entire ecosystems — as well as waters already designated as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

Minimum protection standards established by the federal government in 2019 specifically prohibit a range of industrial activity in MPAs, including bottom trawling. But not all MPAs are protected in the same way, and in some older designated areas trawling is still allowed.

That includes the Scott Islands off the northwestern tip of Vancouver Island, which was designated a year before government standards were put in place.

The islands attract up to 10 million migrating birds every year, providing key ecological breeding and nesting habitat for 40 per cent of B.C.’s seabirds. According to the federal government, the islands support 90 per cent of Canada's tufted puffins and half of the world's Cassin's auklets.

AIS data suggests the surrounding waters have been heavily trawled in recent years, Pacific Wild found.

In other protected areas — like the Hecate Strait and Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reef MPAs — trawling is prohibited to protect the already damaged glass sponges estimated to be 9,000 years old.

When Lester examined AIS data for the nine factory trawlers, he found nearly 50 instances where they crossed through the sponge reef MPAs moving at trawling speed — something he said suggests they could be violating orders under the Fisheries Act.

“We can't say for sure that they were fishing in MPA areas, but the evidence strongly suggests it,” said Lester.

Ahnert pushed back against such suggestions. The industry representative said “AIS data alone does not indicate when or whether a vessel is actively fishing” and that several other activities “can appear similar to fishing movement patterns in AIS records.”

“The characterization that a small number of trawl vessels are having an ‘outsized impact’ on B.C.’s fisheries does not reflect the reality of how this fishery is managed,” said Ahnert.

Questions over on-board transparency, corporate shift in B.C. trawl fleet

One reason it’s difficult to verify whether the boats ever breached federal fisheries laws is because DFO removed observers from the vessels during the COVID-19 pandemic and installed cameras in their place, according to McAllister.

The Pacific Wild co-founder said documents obtained through the Access to Information and Privacy Act show DFO has handed out penalties to trawling ships for violating the MPA rules. Those documents also show the cameras often fail, he said.

“If you look at the infraction reports, it's all about the camera's not working. The camera's not turned on. Fish scales on the front of the lenses,” said McAllister. “That's our only transparency now.”

Pacific Wild said it went to great lengths to try to access the camera data. McAllister said DFO turned them down, saying the footage was owned by industry.

As part of their investigation, Pacific Wild's team of researchers also filed federal records requests to determine which trawling vessels had been granted licences by DFO. The group says the fisheries agency ultimately denied them any information before 2025, citing privacy concerns.

In addition to the nine factory trawlers at the centre of its investigation, Pacific Wild says it had also been monitoring another 30 to 40 smaller “wet” trawl boats operating in B.C.

Such smaller trawl boats first began operating in B.C. waters just before the First World War. But according to some experts, it was only in recent years that the quota for B.C.’s groundfish trawl fishery has increasingly been concentrated into the hands of corporations and investors.

In a 2023 brief to the federal Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, University of British Columbia fisheries professor Villy Christensen presented research that showed the part of the quota controlled by independent owner-operators has decreased over the last 25 years from around 90 per cent to less than 15 per cent.

For McAllister, the evidence suggests a pattern of factory trawlers contributing to overfishing in the North Atlantic, finding a new owner in Canada, and then somehow convincing the Canadian government to allow the ships to shift operations to B.C. despite bans on such vessels on the other side of the country.

“It's the most wasteful fishery that produces the fewest jobs and fewest benefits for Canadians,” said McAllister. “It’s just the wild west out here.”

‘A dead fish is a dead fish’

Ray Hilborn, a professor at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, said the arrival of the nine factory trawlers on B.C.’s coast in recent years is a result of companies trying to create economic efficiency, a practice that is “pretty standard” in other places in the world.

Hilborn spent years working with DFO and acknowledged that he carried out stock assessments for the B.C. troll fleet several decades ago. For the past 15 years, however, he said he has led international study teams on the impact of deep water trawling around the world.

The researcher said there’s been a global campaign to tear down the trawling industry for decades — a campaign he says this year leaned on Sir David Attenborough's latest film and “would like to blame all the problems of the oceans on fishing.”

The reality of trawl fishing in B.C. he said, means each vessel has a share of the fisheries quota, with the bigger boats inevitably taking more of the catch.

“A dead fish is a dead fish no matter which boat caught it,” Hiborn said.

By targeting the most ecologically rich areas off B.C.’s coast, Pacific Wild claimed through its investigation that the trawling industry’s actions have been equivalent to “clearcutting the ocean floor.”

Anhert said the B.C. groundfish trawl fishery is one of the most heavily regulated and scientifically monitored fisheries in Canada and works off a “precautionary, science-based management framework” developed by DFO.

“In 2022, the trawl fishery operated in less than six per cent of the available bottom habitat, refuting claims of a widespread or indiscriminate impact,” Anhert said.

Hilborn also pointed to those numbers, saying the idea that B.C.’s trawling industry was “clearcutting the ocean floor” is “total nonsense.”

“This clearcut idea is totally crazy because they fish the same place over and over again,” he said. “Why do they keep going back to the same places? Because the fish are still there.”

Hilborn said he doesn’t have any specific knowledge about the ecological richness of the areas factory trawlers are fishing in B.C. He added target fish stocks have been sustainably managed since the industry entered an agreement with the David Suzuki Foundation in 2010.

“The B.C. trawl fishery is at a higher environmental standard than anything else you're going to find in the grocery store,” said the fisheries professor.

“The idea that somehow the B.C. ecosystem is being destroyed by trawling — it's not true.”

For Lester, such comments are misleading once you start to see where the factory trawlers operate.

“I don't know why [Hilborn] missed it, but the rest of the water is over the abyssal zone, and these trawlers are hitting the most productive narrow strip that is along the B.C. coast. That's where most of the life is,” Lester said.

“They're hitting the percentage that matters the most.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story listed three bird species that are not found on the Scott Islands.