A milestone has been achieved for mapping the history of insects in the world, specifically in Princeton, as two new fossils of the dragonfly order of insects have been discovered that are around 50 million years old.

Descriptions and names of the fossils were recently published in the scientific journal The Canadian Entomologist by paleontologist Bruce Archibald of the Beaty Biodiversity Museum of the University of British Columbia and Robert Cannings, an emeritus entomologist with the Royal British Columbia Museum.

Archibald said that there's a beautiful record of fossil insects in British Columbia of the age that he is looking at, which is about 50-51 million years ago.

“What I'm interested in is not that long after the extinction of the dinosaurs. So what's happening is, that the world is starting to become modern,” he said.

“It's no longer this really weird Mesozoic time of dinosaurs and weird plants and also things like that. Now we're in an age where we're beginning to see the modern world emerge. And insects are really useful for that, I see a lot of modern types.”

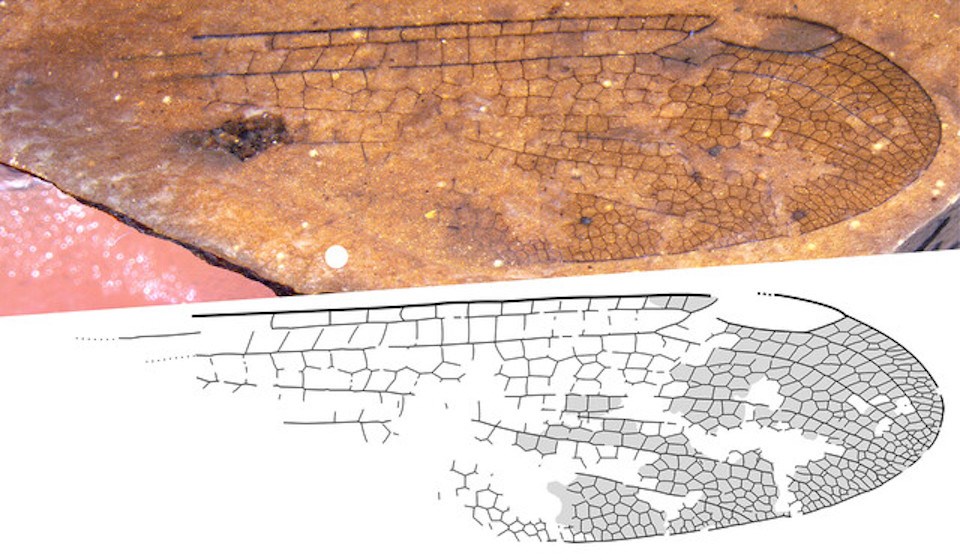

One of the fossils is a dragonfly in the Darner family, which is very common today, according to Archibald.

“That wouldn't look at all out of place by a pond or outside the backyard,” he said. “The other one is a relative of dragonflies, which is an extinct group, which entomologists would say ‘Well this is really weird, this is different.’”

The main difference between the damselflies or dragonflies with this species is that their heads and eyes would look very different.

Princeton has long been known for insect fossil discovery, with collection being done in the region for close to 150 years.

George Mercer Dawson of the Geological Survey of Canada first reported fossil insects in British Columbia in 1877. He reported having found them near Princeton on the banks of the Similkameen River.

Archibald said that over the next century, scientists would come and collect fossils, studying the insects, but no one has ever found a dragonfly or dragonfly relative.

That was until Princeton residents Kathy Simpkins, manager of fossil collections at the Princeton Museum, and Beverly Burlingame, an avid collector who regularly brings fossils to the museum, sent Archibald a picture of their discovery.

“I work quite closely with them, they find fossils and they take cell phone pictures and text them off to me right away,” he said with a chuckle. “And I said, ‘Wow, this is great. You guys this is the catch of the month or the catch of the year even,’ because they found these two.”

The member of an extinct relative of dragonflies and damselflies that Archibald and Cannings identified were named the “Cephalozygoptera” earlier that year.

“It's really nice to fill in this gap and start to understand more about this community and understand how dragonflies and their relatives emerged at this time, the changes that we're going through in British Columbia.”

Identifying the fossil's age comes down to understanding what was happening in specific time periods and in that climate.

“The Princeton area was cool upland in a very warm world with high carbon content in the atmosphere,” Archibald said. “ Along with this high elevation in this uplift went a lot of volcanism, so there are volcanoes going off and regionally and in throughout southern BC.”

Scientists can look at how much of it the ash in the fossil has decayed and reverse engineer it to figure out how long ago the ash came out of the ground.

Archibald spends time speaking in Princeton, working with the town, the museum and the Upper Similkameen Indian Band on discoveries. He plans to be back in the fall for another talk.

Another series of important fossils have been discovered and these will be published over the next few years.

“I see doing his job is a big ecosystem of people and it's the job of this job is to figure out how the world became modern. After this big disaster, the extinction of the dinosaurs. And so far, it's going really well, we're just leaping ahead.”

To find out more on Archibald’s research visit his website here or to read his paper documenting the dragonfly find it online here.