In just over a week, many of us will be heading to the polls to vote in the provincial election — but almost as many of us won’t.

In the last provincial election, voter turnout in B.C. was about 52 per cent, and even lower in Richmond.

We’re bombarded with messages to vote. The notion of mandatory voting has even been bandied about. But I think a better solution lies in wait; one that the voting public may need time to digest.

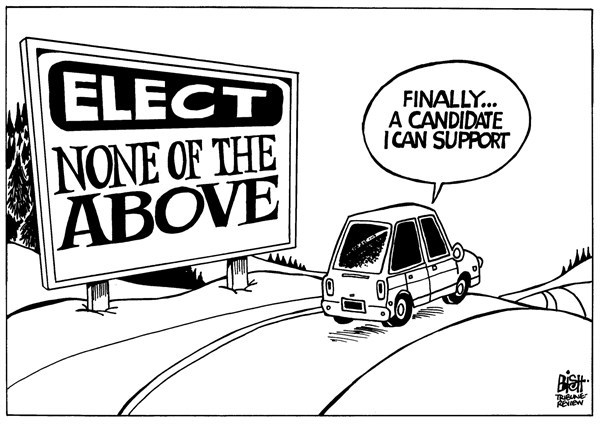

I’m talking about a “declined vote” option, or a vote for “none of the above.”

This measure has been accepted — in some form — in other parts of Canada, and the world, and is essential to the draconian mandatory voting proposal. Democracy Watch argues, in the absence of a declined vote option, mandatory voting is a violation of a person’s right to refuse endorsing a candidate.

As it stands, we’re led to believe eligible voters who don’t vote, don’t care.

I disagree. Nearly all of us care about politics in one form or another. It’s simply expressed differently. For many who do not vote, they aren’t able to express themselves effectively in the present system. They may not like their options or may feel that the system is such that regardless of who gets in, nothing would really change.

By declining your vote, you’re saying, “I am an engaged citizen; I just don’t accept these choices.”

I contend a declined vote option can better gauge what portion of non-voters is dissatisfied or simply apathetic. Perhaps a write-in reason could further inform us.

Last election, only about one in five eligible voters chose Teresa Wat. Hers was the lowest riding for voter turnout in B.C. (43 per cent). Immigration patterns may have played a role here, which is important to note; declined voting only really comes into play when you can rest assured citizens are aware of the electoral process.

Declined voting will not, and should not, alter election outcomes. It’s merely an indicator that can help delegitimize propagandistic claims of minority-elected officials.

In Manitoba, a voter can write “I decline” on a ballot. In 2016, about 4,000 voters (or one per cent of voters) did so, up from 440 in 2011. Here in B.C. there is no such option.

In Nevada, the “none of these candidates” has a designated tick box (much better). The U.S. presidential declined vote soared from 5,770 votes (0.57 per cent) in 2012 to 28,863 (2.56 per cent) in 2016.

The numbers are still low, but probably because the option isn’t well known; after all, no one’s curb-side with “None of the Above” signs — although one Ontario candidate recently registered with the name “ZNone of the Above” to protest Ontario’s lack of declined vote option!