Huddled under a small umbrella as the relentless rain pulsed over the west dyke from the Strait of Georgia, Harold Steves pointed to the bedroom window where, as a four-year-old boy, he stared out in awe at the anti-aircraft guns being fired a few yards away from his family home.

In close proximity to the powerful artillery — which was partially protected from enemy fire by the dyke — were two, 18-pound anti-ship guns, mounted on the west dyke, right next to Steves’ farmhouse, ready to be aimed and fired at any unidentified vessels trying to approach Steveston and the B.C. coast.

Barbed wire extended across the marsh to protect ammunition, while army barracks for the 75-strong battalion were planted 250 yards east of the dyke.

Steveston Highway was also closed off at Sixth Avenue with a barricade and an armed sentry; the Steves family of four being the only civilians allowed in and out.

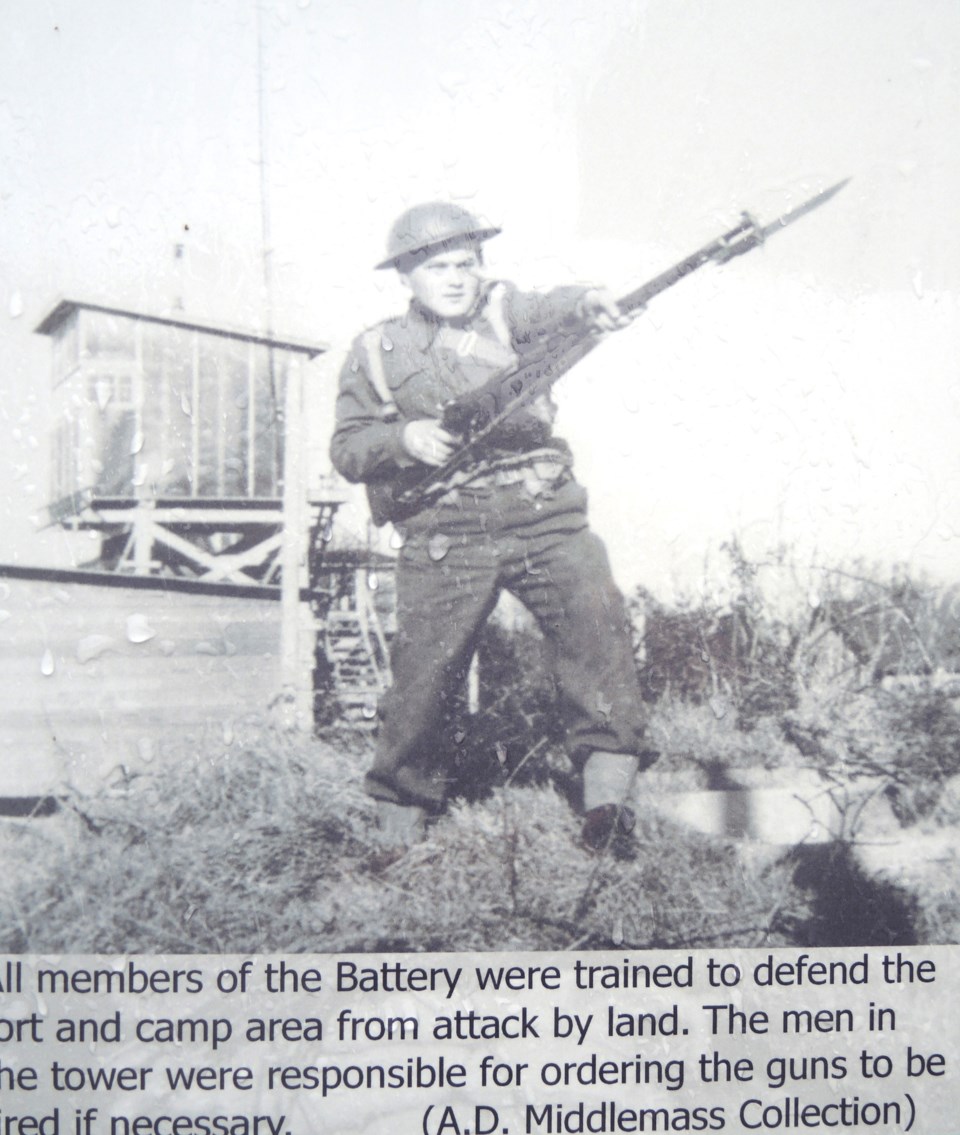

As he mopped the precipitation from his brow with a hankerchief, 79-year-old Steves peered through the gloom along the dyke at what was known as Fort Steveston, fully-manned and operated from 1939 to 1945 by the 58th Battery of the 15th (Vancouver) Coast Regiment of the Royal Canadian Artillery.

“(The army would) tell my folks that they’d better open the windows a little,” grinned Steves, recalling that, when the regiment was testing the guns, his parents had to open their farmhouse windows, lest the glass shattering with the piercing crack of the artillery.

“I remember as a little kid, we had to open the windows often and we would be in there, with the curtains blowing all over the place and rain coming in.

“I could see them firing the guns from my bedroom window; the naval gun was right in front of my bedroom window and the anti-aircraft gun was right in front of the house; we watched that one through our front window.”

Veteran city councillor Steves also remembers with some amusement the sight of the soldiers doing practice runs with First World War Howitzer guns, wheeling them up and down Steveston Highway to the dyke, from a camp between Sixth and Seventh avenues.

“I think they kept (the fort) for gunnery practice for a few years after the Second World War,” added Steves, noting that the primary role of the fort was to support the Royal Canadian Navy in protecting the south arm of the Fraser River.

“I remember having our windows blacked out with tar paper and, one time, a soldier standing guard at our breakfast table with a gun to make sure we didn’t open the windows.

“You don’t forget those things; these are very vivid memories I have about being a little kid here.”

The Japanese are coming

Gesturing from his dining room — which could itself pass as a set for a Second World War movie — towards the far corner of his antique-filled lounge, Steves pointed out a large, gramophone-style device.

Staring at the dusty, clunky radio, Steves wound the clock back to the evening of Dec. 7, 1941, the infamous day the Japanese launched its devastating attack on Pearl Harbor.

With his parents glued to the grim commentary from the announcer, Steves — despite being only four-years-old— remembered clearly what he was doing at that fateful moment in history.

“I remember clearly my parents sitting there, intently listening to the broadcast and I was playing, having a merry old time, as Pearl Harbor was being bombed,” smiled Steves.

“I remember climbing into a cardboard box, pretending to be the radio announcer broadcasting the news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. That’s the reason I kept (the radio).”

One of the many unconfirmed wartime reports of those tentative, post-Pearl Harbor days was of a Japanese submarine bombing a remote location off the west coast of Vancouver Island, with the possibility of an enemy submarine advancing unmolested down the Strait of Georgia.

Steves doesn’t recall who told his family, but he does recall the ears of a young, inquisitive boy pricking up now and again.

“I know that my parents were sworn to secrecy, but (the army) generally told us what was happening and I overheard them as well,” he laughed.

“I’ve heard of the apparent shelling by the Japanese further up the coast, but don’t know any more details.

“I do remember there was a concern that the Japanese would come down the strait, but nobody seems to know why they turned around and went back. I’ve tried to research this, but found very little.”

There’s also a little, shiny nugget of knowledge, said Steves, about a sub being spotted in the mouth of the Fraser River, although he has not been able to find anything of record.

“George Fentiman was the keeper of the lightship at the end of the Steveston jetty and he apparently saw, in the moonlight, a submarine,” said Steves.

“He saw a guy standing there on the tower of the sub. He put it in his diary and reported it to the authorities; apparently he saw it two nights.

“(Fentiman) was my dad’s best friend, so we got that story pretty fast. However, there was a suggestion it was maybe a German sub; maybe due to the shape of the tower?

“I was on a radio show in the 1960s talking about this and, afterwards, some German guy called me up on the phone and said he was on that sub and was stationed in the Strait of Georgia out there. I’m not sure how true that is!

“I do also recall hearing what we believed to be depth charges getting dropped in the river, but I can’t find any record of that either.”

Game warden, owl were the only Fort Steveston casualties

An imminent Japanese invasion aside, growing up in the shadow of Fort Steveston, the only true enemy Steves could recall was that of the local game warden, who used to guard the west dyke and its seasonal snow geese population from illegal hunters, including the fort’s soldiers.

However, patrolling the same patch during the war effort were MPs (military police), who were less discerning in who they rounded up if caught roaming on the west dyke marsh.

“The game warden was out there in the marsh, dealing with some soldiers who were hunting snow geese, illegally,” laughed Steves, who learned to hunt the geese on the dyke while tagging along with his uncle and, sometimes, the soldiers.

“But the MPs ended up arresting the game warden, as well. So, the warden got thrown into the guard house — at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Steveston Highway — with the soldiers; it was the talk of the camp for days.

“I remember we were quite happy to know that the warden was out of the picture for a little while.

“So, the only arrests made at Fort Steveston were the game warden and, I think, an injured owl.”

Lt. Col. Steves reports for duty

Being the only kid on the block (fort), aside from his baby brother, Steves was the natural choice for the regiment’s resident mascot, a job which came with a replica, scaled down army uniform and the responsibility to periodically inspect the troops.

After gently producing from a clear, sealed plastic bag (his mom took care to preserve artifacts) the same uniform he wore 75 years ago, Steves remembered with fondness his “duties.”

“As mascot for the camp, I inspected the troops all the time; it was quite formal, as I recall,” he said.

“We were the only family inside the military line there at Sixth Avenue and, as the army were, in effect, renting half the farm from us, I think they liked to include us when they could.”

Steves’ parents also created in their basement an unofficial, army camp canteen, which had the soldiers lining up outside.

And like many things in the Steves house, it has been well preserved; so much so that he intends to open up a public museum in his basement.

“I’m told the soldiers didn’t like the camp food, so my parents set up this canteen with tables,” said Steves, pointing to a table and chairs in his basement, the very same ones used by the soldiers during the war.

“We had this pie safe, as well, which would have been filled with home-made lemon meringue pie and apple pie.

“Breakfast and lunch was served and the soldiers would be lined up outside the door waiting to come in. I grew up with these soldiers in the house.”