A throng of curious onlookers, from young children to seniors, stand and gape at the rapid precision movement of the Makerbot Replicator 2’s inkjet printhead. It is, indeed, a marvel to watch the desktop machine etch, layer by layer, a tiny, three-dimensional figurine right before your eyes. Of course, printing three-dimensional items could take up to minutes, even hours, depending on the scale, complexity and desired resolution (i.e. higher resolution equals smoother cuts and edges) of the design.

The particular MakerBot in action has been pumping out small to medium-sized objects for the last few weeks at Brighouse Richmond Public Library and kids of all ages seem to enjoy it immensely, though few understand the technology.

Making them understand is the ultimate goal of any library, says Susan Walters, Richmond’s deputy chief librarian. “Our role is to educate.”

Yoko — as per the yellow sticky-note stuck to its PVC exterior — is just one of three desktop machines stationed at the Brighouse branch. The others, John and Sean, make up the small 3D printing contingent within the library’s dedicated e-space dubbed the “Launchpad.”

This is the library’s re-positioning for the future, or at least preparation to embrace the ensuing change.

It’s an electronic age, explains Walters. 3D printing is just the latest edge of the technological revolution. Helping the cause are the inventions and digital improvements to traditional constructs like books, distribution of music, video and the news. But the library is not interested in simply promoting technology for technology sake, explains Walters. Rather, it’s aim, is (as it’s always been) to provide greater access to a wide range of information and ideas. The growing movement within the library is to adopt the digital world, to inspire innovation and creativity by providing the portal to a myriad of possibilities.

The Launchpad

“Taking you to tomorrow” is written in large white font on the banner that streams across the library’s Launchpad showcase. This hub, a small cross section on the first floor of the library, demarcates the encroachment of an ever-expanding e-lifestyle. This isn’t something new, but the advancements certainly are.

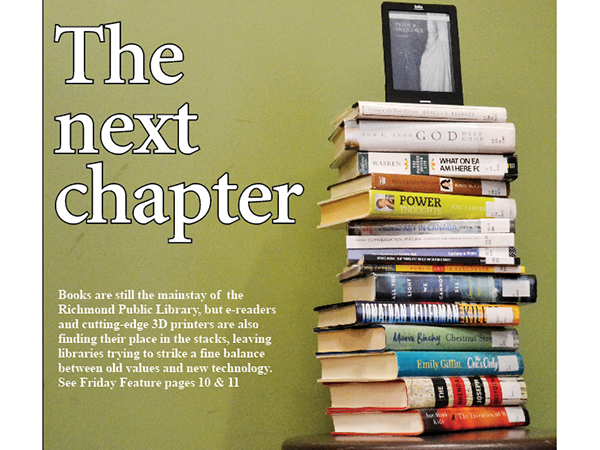

Ebooks, audio, evideo, magazines, music and enews represent the core facets of the library’s Go Digital movement, however not all are keen to change.

“After public consultations with members of the community, we found that about fifty per cent of respondents were still rooted to the traditional medium,” says Walters. “This is the challenge.”

Serving all ages is a critical tenet of the library and Walters says there are currently three categories library users fall into.

There are the traditionalists who still believe print is king, there are those who are 100 per cent digital and then there are those who fall somewhere between.

With such a spectrum, it is obviously impossible to cater to all needs with a one-size-fits-all approach, explains Walters.

The Launchpad is therefore, and as the name suggests, a jumping off point. It’s a space, staffed full-time, designed to bring everything electronically related, into one place, for users to visit, view, interact and use. In essence, it’s the digital world in a physical space.

As Walters explains, the library is one place in the community where everyone can come to and access a wide range of resources. Technology is simply affecting those resources, inspiring creativity and imagination, no matter the format or medium. The Library is therefore in the midst of change and the Launchpad signifies the move to blend old needs operating via new platforms.

The digi-nitty gritty

Richmond Public Library has always embraced change, says Walters.

Representatives from other libraries came from all over North America to witness the pioneering changes initiated by then deputy chief librarian Cate McNeely who was instrumental in creating Richmond’s “library of the future,” the Ironwood branch back in 1998.

Services such as a computer training centre, designated Internet stations and digital Reference Centres for adults and children were the cornerstone products of the then state-of-the-art library. Times have certainly changed and continue to do so.

Despite the estimated 50/50 split between traditionalists and new-age embracers as per the recent public consultation, there has been a steady hike in e-usage.

Kat Lucas, eServices coordinator for the Richmond Library says, over the four years or so since ebook lending was introduced, the numbers have jumped from around 20,000 checkouts and downloads in 2010 to about 80,000 in 2013 (the numbers for 2014 are not yet available).

This increase of users year-over-year led to the library purchasing 25 Kobo ereaders as part of a new e-lending service. There are 15 designated for adult use, five for kids and five for teens, says Lucas. Up to 10 books can be checked out at any one time and can be held for 21 days. At the end of the lending period, the book is “returned” automatically, extinguishing any late-fee concerns and enhancing convenience for the user. In addition, there’s no way to damage the book, although caution over the ereader’s condition must be exercised if it is not your own.

Publisher pricing

The surprising note or myth is that digital is cheaper — and perhaps it is, but publishers aren’t charging less. Lucas says publishers ascribe different levels of cost in relation to a digital product, be it a piece of popular fiction, non-fiction or a children’s book. To compare, for example, a hardcopy book could be bought at $30 a piece by any one library. A set of 10 or 20 could be purchased with the publisher knowing these copies would potentially require repurchasing at a later date due to wear and tear.

The same is not the case with digital products, thus the cost per copy comes at an inflated rate, set by publishers, each of whom ascribe different price tags. One publishing house could set the cost at $100 per year, per digital copy of a book, that the library can lend to one user at a time. Other publishers may set the rate at $90, or $75 per book. In short, the logistics are by no means standardized as is the case with the traditional print medium.

Nonetheless, the library works to update its catalogue of ebooks — by far the most popular electronic borrowing product — with the latest addition being a collection of Chinese ebooks.

The demand is there, Lucas says of digital products. But just as the e-movement begins to harden into the mainstream, and the library grapples with the change, an even greater shift to embracing creativity and self-service is underway and the Library remains at the forefront.

Makerspaces emerging

3D printing signals an embracement of next-generation technology and the advent of what’s being called “makerspaces.”

“A lot of libraries are beginning to include these kinds of spaces,” says Ray Lam, marketing and communications coordinator at Richmond Public Library. He admits, Richmond isn’t leading the charge, but they aren’t far behind the pioneers.

The goal is not to transmogrify the library into a digital wonderland, but rather to do what it’s always done which is to educate and enlighten the community — hence the hiring of innovator-in-residence Graeme Bennett.

Bennett specializes in 3D printing, both in use and construction of the devices, and he says the technology is something that, while still in its infancy, is an absolutely revolutionary technology.

To churn out a 3D work of art, it begins by constructing a 3D design within CAD (computer-aided design) software. After the design is complete, the CAD software will provide you with a STL (Standard Tessellation Language) formatted file. This is the format most, if not all, 3D printer software can read.

There are several open source programs like 3dtin, Sketchup, OpenSCAD, Wings3D, and Blender that beginners can use to play around with, in addition to several commercial applications currently in the market. Conversely, 3D scanning technology is slowly growing into a viable reality whereby an object could be placed on a device and a 3D rendering is accomplished via contact or non-contact (light reflection or radiation) processes.

Though these devices are expensive, progress is being made. U.S. company TRNIO, for instance, released an app that can turn an iPhone into a 3D scanning machine, though with considerable restrictions.

Makerbot also makes a 3D scanner for under $1,000, but it too is a rather small device thereby limiting what objects can be scanned.

After acquisition of a CAD, it’s just a matter of uploading the file onto a standard SD card and loading it into your 3D printer, like the MakerBot Replica 2, and presto! In a matter of minutes (or hours) your 3D brain-child is now a reality.

How well your design functions, however, is contingent on the design and the building filament (i.e. the 3D “ink” or product) used.

The Makerbot Replicator 2 uses PLA filament which, as Bennett explains, is corn starch based, making the products produced biodegradable.

Bennett advises that almost anything with a paste-like texture can be utilized as a filament. In China, for example, a construction firm is already in the midst of producing 3D printed homes at a cost below US$5,000.

One UK-based company, Choc Edge, already works to print exquisite and intricate chocolate creations. Another company works to turn sugar-based filament into complex constructs you can eat, admire or both (see 3D Systems’ sugar lab to see sweet crystalline creations).

Bennett speculates the future of 3D printing is far-reaching, though there’s still much room to progress. It boils down to enhancing durability to match the strength of traditional parts and products. Furthermore, crafting just small objects, one at time, is quite cheap. Larger items, on a mass scale, can still carry a considerable price tag. Bennett also believes 3D printing and related technology will displace a number of industries in the not too distant future. Already significant progress has been made especially in healthcare with prosthetics and biodegradable splints (used to prop open a 16-month-old child who was suffering from an absent pulmonary valve.)

It is such advancements, inventions of great significance that were born from knowledge, skill and accessibility to cutting-edge technology, that make the significance of educating and exposing the next generation of thinkers quite clear — and the library’s role ever-more important.

Innovation for all

“The library is an equalizing force,” says Walters. It is free, it doesn’t discriminate and we’ve always been a place that works to provide access to resources and assistance.

In the ensuing months, Walters and Lam insist the initiative is to open the space up for members of the community to come and access the 3D printers for their own, unique projects.

The move is towards self-service, Lam mentioned. The library is also looking into self-publishing technology, something like the Espresso Book Maker, so people can publish small works of art, like a book of poetry or short stories that could then be distributed on a small scale.

Richmond Public Library is embracing change, embracing innovation. The move toward more robust e-services, which, like a personal computer, are advanced tools that can be used to learn, manage and create and all free of cost is a sign of the new age toward empowering citizens to think and do more. And it all starts with exposure and low-cost access.

The library hosts tutor sessions and plans to hold one-on-one scheduled sessions in the near future.