The strip of bacon sizzles in customary fashion as it contacts the hot skillet, heralding the morning breakfast ritual.

Shrinking by about a quarter of its original dimensions as it cooks, the rasher renders a small pool of fat that beckons a slice of white bread for a British delicacy — fried bread.

You can almost hear the collective gasp of shock and horror from the health-conscious segment of society brought up on a steady diet of low fat meals.

But a retired Richmond doctor is turning on its head that decades old mantra of removing as much fat as possible from the dining table to provide a healthy diet.

Dr. Richard Mathias, professor emeritus from UBC, is espousing a return of saturated fats to meals, while at the same time reducing carbohydrates in a war against obesity and its related illness such as heart disease, diabetes and cancer.

So banish the carb-loaded white bread and bring on the bacon?

Historical wrongs

Mathias, who was a public health epidemiologist, said public health officials got things wrong as far back as the 1950s when then U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower suffered a heart attack.

The event shocked North American society and prompted health experts into recommending a low fat diet as a way of reducing the risk of heart disease. It was called the Diet for America.

Experts of the time concluded cholesterol levels were a major factor in heart disease.

“And they are,” Mathias said. “But the leap made was that the major control for cholesterol levels is dietary intake. And the dietary intake associated with cholesterol is fat.”

Mathias said the logic of the time was impeccable, but the evidence was lacking.

Mathias contends the opposite was true — fat was less harmful and carbohydrates were the real culprit, and western society has been paying the price ever since as cases of obesity have worsened over the intervening decades.

In 2013, members of the American Medical Association voted to label obesity as a disease.

In Canada, a study from Memorial University in St. John’s indicated obesity rates in Canada tripled between 1985 and 2011. Plus, another study published by the Canadian Medical Association Journal projects that about 21 per cent of Canadian adults will be obese by 2019.

Mathias said studies back when the Diet For America was being formulated that linked communities with a high intake of dietary fats to heart disease were fraudulent.

“But what we in public health did was tell people to reduce fat intake, and increase carbohydrates.”

The food industry followed that up by ramping up carbs and reducing fats in their products.

The result was a sugar consumption spike.

Fats were demonized when in fact what they had going for them, Mathias said, was the production of the hormone leptin which provides a body with the sense of satiation and regulates the amount of fat stored in the body.

“So, what we were doing was taking that feeling of satiation away by removing fats and giving people simple sugars through carbohydrates that kicks up production of insulin and makes you feel hungry. So, you’ve got a situation where you don’t feel full and have an increased feeling of being hungry.

“What do you do then? You eat.”

Mathias said in that case it’s no longer a question of dietary choice for an individual.

“It’s what your body is telling you to do, and generally, people respond to that.”

Plain and simple, public health experts blew it, Mathias said.

“Carbohydrate intake has just gone shooting up over the last 40 years because public health advice was wrong,” he said

New theories, new diets

Mathias is not alone in his suggestion that a diet containing saturated fats is not as damaging as long considered.

A 2011 study done by the University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands states that “the dietary intake of saturated fatty acids is associated with a modest increase in serum total cholesterol, but not with cardiovascular disease.”

The study adds that replacing dietary saturated fatty acids with carbohydrates, notably those with a high glycaemic index, is associated with an increase in cardiovascular risk.

But don’t grab that big box store-sized package of sausage or bacon just yet.

According to Health Canada, some saturated fats are still considered bad and advise a limited intake. On its website, fats from animal foods — including beef, chicken, lamb, pork and veal, plus butter, cheese, whole milk, and lard — are among the bad, saturated fats.

More beneficial saturated fats are ones found in avocados, nuts and seeds, plus vegetable oils such as canola, peanut, sesame and sunflower.

It’s a recommendation Richmond registered dietician — and News columnist — Katie Huston recommends to her clients.

“There’s always going to be controversy over nutrition and diet, but we still recommend limiting saturated fats for people who have heart disease, high cholesterol or diabetes — people who are at higher risk,” she said.

But that’s not to say low-fat diets taken to further, more extreme lengths provide even better health benefits.

“Quite a while ago there was this low fat craze, whereas today we know we need some fats in our diets,” Huston said.

That’s why she recommends that 20 to 30 per cent of caloric intake be made up of from fats — good ones.

“Getting that from nuts and seeds, or oily fish being the main ones,” she said, adding oils derived from vegetables, but not tropical ones, should be included.

And don’t banish all carbs.

“We do know that soluble fibre limits cholesterol, which you cannot get without healthy carbs, like fruits, vegetables and whole grains,” Huston said.

Was Atkins right?

In the early 2000s, nutritionist Dr. Robert Atkins popularized a diet not unlike what Mathias is espousing today.

“He (Atkins) was not totally wrong about this. He was totally right,” Mathias said. “We now understand why it worked.”

Mathias explained that high-carb diets stimulated the production of bad cholesterol in the body which led to heart disease.

“He (Atkins) said if you are going to consume carbohydrates, don’t choose the ones that have high levels of sugar,” Mathias said, adding that meant cutting out potatoes, other starchy foods, and foods which have been genetically modified to taste sweeter.

That said, the Atkins diet has been criticized for not including a sufficient amount of fibre.

Which direction to go?

With all the advice — often conflicting — circulating out there on what’s best to eat for a better, healthier life, and how do you find one that’s right for you?

Huston said it’s wise to remember there’s not a “one size fits all” diet that will work for everyone.

“That’s what makes it challenging. And sometimes the guidelines take a while to catch up with the research,” she said, adding she’s not surprised by the apparent about-face with saturated fats that Dr. Mathias is touting.

“There’s been a lot of the demonizing of fats in general,” she said. “And we do need fats. They are an essential part of our diets.”

As with much discussion on health and foods, the “M” word — moderation — comes into play.

“Moderation is so important. It’s a case of looking at things and thinking no foods should be forbidden, but sometimes we forget that,” Huston said “There’s no one, right answer, no quick fix, as much as we wish there was.”

Eat from a Healthy Plate

From a local public health perspective, what constitutes a healthy diet?

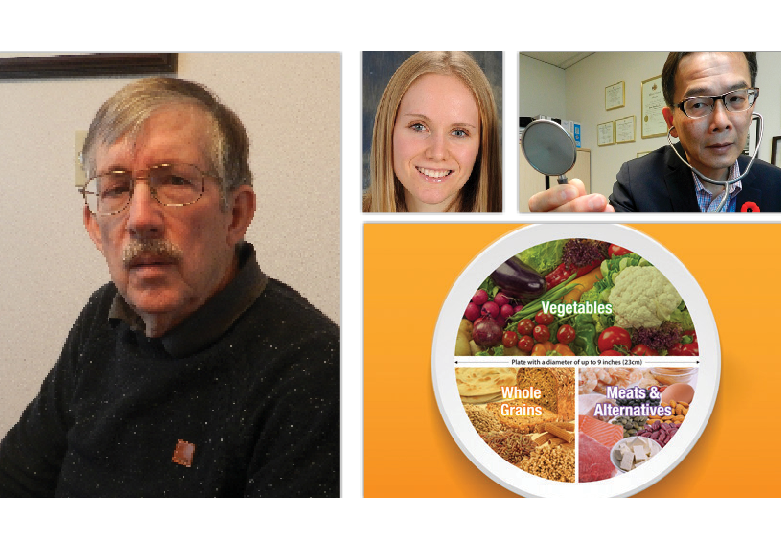

Dr. James Lu, Richmond’s medical health officer, said there is a formula Vancouver Coastal Health suggests in its Healthy Plate guide to eating balanced meals.

“What we’re advocating is that when we eat — starting first of all with smaller portions — half of your plate is filled with fruit and vegetables,” Lu said. “A quarter is some sort of protein — fish, meat or vegetarian. And the last quarter be cereals, such as rice or other carbohydrates.”

There is also more attention given to the classic Mediterranean diet, which is high in certain types of oil — most notably olive oil.

“Plus there’s fish and cheese, showing that when it comes to fat there certainly appears to be ones that are not as harmful as others,” Lu said.

However, Lu said he is not detached from the recent rise of suggestions to re-introduce saturated fats.

“I think (Dr. Mathias) has a point in terms of the messaging,” Lu said. “Certainly, the pace of the public health community in terms of changing our outlook is not as fast as what he would like to see.

“As a result, our (public health) message is going to have to be more nuanced.”

Finding a champion of fat

With the discussion now edging back to include saturated fat in diets, what kind of change can be expected in terms of public health advice?

“It’s shifting relatively slowly,” Mathias said.

He likened the pace to that experienced in war against big tobacco and smoking.

“The problem is the issue is caught up in the political process which is resistant to change and requires a champion. People have to champion things,” he said. “In Canada, we do not have a coordinated set of champions. But they are getting them more and more in the U.S.”

But make no mistake, Mathias said he believes society is entering the early stages of a war with the food industry to address obesity issues.

“Bureaucracies have recognized we have a problem,” he said. “They just haven’t been able to shift their paradigm to the solution. That’s how I perceive it. Medical health officers have recognized it, too, but haven’t developed the political will to shift to where it needs to be.”