Their friendship has endured for as long as their professional lives as sculptors, which after close to 50 years shows no signs of ending anytime soon.

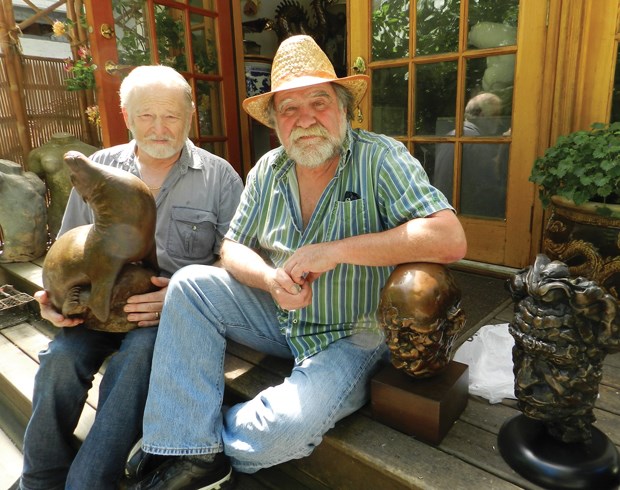

So, for Richmond’s Alex Schick, 69, and Cliff Vincenzi, 66, the opportunity to once more be featured in the same art show adds just another page in their storied past.

Their work will be on display July 31 to Aug. 4 in the Sculptors' Society of BC's Summer Exhibition at Van Dusen Gardens in Vancouver.

While they both graduated — two years apart — from Richmond secondary, they only got to know each other well when they attended Vancouver School of Art in 1968 and began setting up studio space.

“Then we really got to know each other when we lived in Gastown, illegally in our studio,” Vincenzi said laughing.

“Twenty-five bucks a month,” Schick says with a smile. “It was $5 for electricity. One light bulb.”

“And you’d share a bathroom with 10 to 15 people,” Vincenzi quipped.

Vincenzi had earned a scholarship from Richmond secondary which encouraged his parents to accept their son’s career path.

“My dad wanted me to be a fireman because he was one. But the fact I got a scholarship to go to art school, he thought maybe something will come out if it,” Vincenzi said, who had thoughts of becoming a commercial artist when he enrolled at the Vancouver School of Art.

“But that quickly changed when I saw the senior (art school) sculptors working on the human form,” he said. “From then, I knew that was all I wanted to do.”

Students had to wait until second year to enrol in sculpture classes, but the instructor spied the young Vincenzi in the classroom, watching the older students at work and encouraged him give it a try.

“He inspired me, because the first year you usually take drawing, painting, print-making, that kind of stuff to give you a feel for where you want to go. And I just knew sculpture is what I wanted.

“Then I stayed there seven years, and it’s a four-year course,” Vincenzi said, adding in the latter years he was using the art school as a studio since it had a foundry where bronze could be poured.

For Schick, the road to art school was a little less direct.

“My brother and I were drawing ever since we were little kids. Anything that was an open space on a newspaper or anything, I’d draw on it,” said Schick, whose creations are featured in many major corporate collections, as well as the Embassy of the Bahamas and the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC. “But as far as me being an artist as a career, my parents and pretty nobody thought it would happen. I was constantly being told, ‘You’ll never make it.’”

His parents treated him with tough love.

“They figured if they didn’t encourage it, my love for art would go away and I’d get a job,” Schick said. “I came close a couple of times.”

After finishing high school he was working in a sawmill’s power house as a fourth class apprentice engineer.

“And I met this girl and we were going to get married, but she didn’t want a lunch box husband,” Schick said. “So, I thought I need to go to UBC, but how the heck do I do that?”

What he learned from other artists was that if he completed four years of art school, that would credit him for two years of study at university.

“So, I was planning to be an art teacher,” he said, adding he marched off to the art school with an improvised portfolio.

“I just took drawing and papers I had from around the house and stuffed them into a portfolio. And when I got to the interview the head of the school asked me if I had $250? I said yeah. And he said, ‘You’re in.’”

Then, the two met and became contemporaries and friends.

“When I walked through the modelling area where Cliff was working, I saw his sculpture and thought, holy smokes, there’s someone here who’s got talent,” Schick said.

At the school the pair mastered the intricate art of bronze casting and worked with renowned instructor Jack Harman, whose sculptures in Vancouver include one of sprinter Harry Jerome that stands in Stanley Park, and the Miracle Mile depicting the John Landy-Roger Bannister race at the 1954 Commonwealth Games in Vancouver.

“It’s so technical that you either hate it or you love it,” Vincenzi said. “It’s a real challenge. So many things can go wrong.”

But it’s that entire process — from conception to finished product that keep the pair’s creative desire stoked.

“It’s the whole journey,” Schick said. “From the first step off the bike to the walk up the mountain, and the pilgrimage to the top.”

“I couldn’t work on a computer or put a video machine back together, but this kind of technology (bronze casting), I just loved it,” Vincenzi said. “You have to visualize it. The technique is about 8,000 years old.”

The Sculptors' Society of British Columbia’s Summer Exhibition runs July 31 to Aug. 4 at Van Dusen Gardens (5152 Oak Street).

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)