So it’s Labour Day weekend. That last gasp of summer. That prep for the new school year. That commemoration of George Brown. Huh?

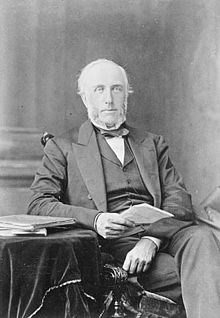

When I hear “George Brown,” I think of the college in Toronto which is, indeed, named after him. In the mid 1800s, Brown was the de facto leader of Canada’s Liberal party and political foe of Conservative Sir John A. McDonald. But what he has to do with Labour Day is the fact that in 1872 he was the publisher of the Toronto Globe, which at the time was the country’s leading newspaper.

The typographical workers there were working 10-hour days, six days a week and were getting, well, rather weary. So, they went on strike, demanding, of all things, a 54-hour work week, which would bring their schedule down to a mere nine hours a day, six days a week — the slackers.

Brown was incensed. Not so much over the hours, but the audacity of workers thinking they could have a say in how he ran his business.

In many ways, Brown was on the right side of history. He was a fervent opponent of slavery, a defender of religious freedom and an advocate for prison reform. His two daughters were among the first women to graduate from the University of Toronto. But when it came to business, he was Mr. laissez faire, let the market decide and give owners free rein.

To quell the uprising, he invoked a little-known law that equated union organization with conspiracy and had the organizers arrested. The move inspired yet another demonstration in Ottawa on Sept. 3. Sir John A. McDonald, although no great friend of labour himself, saw an opportunity to undermine his long-standing rival and vowed to repeal the anti-union laws, which he did the following year. And, yay, now we have a long weekend to mark the September protest.

Obviously, we’ve come a long way from 60-hour work weeks. Our Employee’s Standards Act ensures all sorts of things: breaks during a shift, overtime pay after eight hours, a minimum wage. (We can largely thank organized labour for the above.)

The catch these days is not that employers (at least for the most part in Canada) are forcing people to work crazy long hours — but other factors are. Housing and the cost of living have many folks toiling at two or three jobs to survive.

But what stands out for me in the Brown story is his sense that an owner’s business is theirs and theirs alone. I get that leadership matters and people have their respective roles. Not every decision needs a committee, but does any one person really “own” it all?

Recently, I was reading about the Guardian newspaper in the UK, where editors are elected by the journalists. It’s a radical concept and surely has its flaws (namely, I could be voted out of a job). But it’s curious that the idea of bringing a diversity of ideas and perspectives to governance is something we laud in politics — view, in fact, as the hallmark of a healthy democracy. Yet, we’re so skittish about it when it comes to business.

Maybe that says something about where real power lies.