The rolling, moss-green hills cascading down the length of the rectangular canvas are punctuated by a cluster of globe-like bushes and spiky-tipped evergreens as Jim Young applies some swirling brush strokes.

It’s there, beside a river meandering down from snow-capped peaks, he makes his personal mark.

It’s not a signature. It’s not a stick figure.

It’s an almost imperceptible, light touch with the paintbrush bristles.

But to Young, it’s designed to indicate his presence — placed amid the pastoral splendour of his own creation.

“I do this all the time, put myself in my paintings,” says Young, 61, who suffers depression and uses art as a release from the ever-present feelings. “I tend to lose myself in my paintings. But that’s where I want to be, in my mind.”

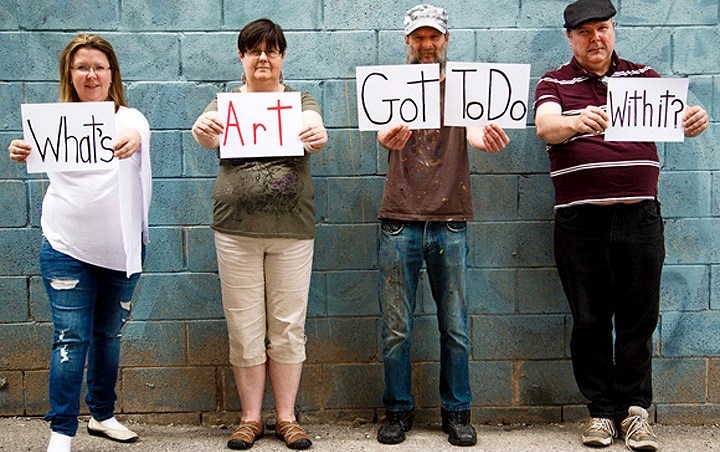

Young, who works part time at Pathways Clubhouse in Richmond, is one of several artists with mental illness who will be showing their work Oct. 8 at the Twenty Years of Wellness Art Show staged by the Richmond Mental Health Consumer and Friends’ Society (RCFC) at the Richmond Cultural Centre. The event, celebrating the society’s two decades of local service, is one of several in Richmond marking Mental Illness Awareness Week that runs nationally Oct. 4 - 10.

Channeling an obsession

Young’s landscape is a long way from the comic strip and comic book characters he turned out as a 16-year-old high school student at Windermere secondary in east Vancouver. Back then, he yearned to make a living from his talents with a pencil, brush, charcoal, and pretty much any artistic medium he could get his hands on.

He managed to do that for a while after graduating from Emily Carr University of Art and Design in the late 1970s, working for a printer, making specialized identity cards for Citizen Band radio enthusiasts.

Away from his day job, Young’s art was his obsession, with weeks spent painting landscapes and portraits in a makeshift, one bedroom home studio in Burnaby.

While his job eventually ended, Young continued with his art.

“I so desperately wanted to be a professional artist, that’s what drove me,” he says.

Commissions came and went, and they paid some of the bills, but the dream still burned brightly.

And while it may not have been a stable vocation, Young says he’s grateful he had it in his life when he quietly mentions, without elaboration, the source of his depression.

“I lost someone very close to me.”

Part of the landscape

The art Young produced, following bouts with post traumatic stress disorder and depression, were dark.

“It was a way of letting my emotions flow through my work with demonic figures, faces, all done with charcoal,” he says. “It was a way of getting out what I was feeling.

“I got a lot of it out on paper. It wasn’t good to bottle all of that up inside. I needed to let it out.”

Today, most of Young’s work focuses on landscapes, but not those reproduced from photos or magazine pictures. They come from his mind; dreamscapes, he calls them — the aforementioned painting is of vast, emerald pastures, not unlike the rolling glens of Scotland near Edinburgh where he lived until age 10 before coming to Canada.

It’s a safe and calming place.

“I like going there. It allows me to feel calm and totally in control of my surroundings because I am the one who has created them,” says Young, explaining why art therapy — done on his own and through more formal means — has helped him over the years with his continuing mental health condition.

“It’s my place. It’s beautiful. It’s safe.”

So, too, is the company of other artists that Young enjoys when he makes the trek in from Marpole to take part in the monthly painting sessions hosted by RCFC.

“Being there, it’s very important,” he says. “It’s like a family. It’s very inspirational and I feel secure there.”

That’s the environment Barb Bawlf, executive director at RCFC, said she envisioned when she created the classes, which are part of the society’s recreational programming. In 2013, the art show, stocked with some work created during the meetings, was added.

“A lot of local people suffering from mental health issues have done art for years and nobody has really recognized or seen it,” says Bawlf, adding the sessions have also helped break down barriers that inhibited some people from coming forward and lend their hand to art.

“There are people I didn’t know were artists who have come out of the woodwork,” Bawlf says. “And the classes have been very positive in that respect. It brings a real sense of community for those taking part in them. It also provides, I think, a big boost in self-esteem and confidence.”

With the current void of a full-time art therapy program in Richmond, Bawlf says RCFC’s informal efforts try and fill the gap.

Hopes are the art exhibition will live on at local community centres. That potential for added exposure would be beneficial, Bawlf says, adding she wholeheartedly believes in the role of art in mental health recovery.

“I’ve seen people be able to take on paid work and volunteer for things they may not have been encouraged to do before. That’s one of the good outcomes of participating in programs like this,” she says.

Two views of art

Teresa Massel believes in the healing power of art, too.

As someone who has spent 20 years working in the field as an art therapist, she also sees the ability for art to reveal important clues to an individual’s condition.

“To me, it’s an invaluable communication tool. In the hands of an art therapist, a client can benefit the most from not only the experience of making the art, but having a final product to look at and gain greater self awareness about their personality, their issues and their illness,” Massel says.

“It’s right in front of them. They can see what they’ve done. They can’t deny it. It’s a visible art product that reflects their inner world — their thoughts and their feelings.”

Massel says an art therapist is a kind of facilitator or guide who is able to see where a person is in their recovery, and where they can go.

That process can sometimes be hampered by verbal communication barriers, which, in some cases, art can remove.

“If you see it (art) as a symbolic form of language, it can open a window or a door into a person’s verbal language,” Massel says. “There are some people who are so unwell, they maybe can’t say much. And there are art therapists who believe it’s not always necessary to talk and analyze their art. There is also benefit from the person to just express themselves, non-verbally making an art product. That can make a difference in someone’s recovery.”

But when possible, Massel also encourages discussion of the art that is produced.

“To me, it helps someone who has expressed themselves non-verbally to acquire a language for what they are expressing,” she says. “That’s why I enjoy the group art therapy so much. I think people benefit from talking to and listening to each other.”

The creative part of being an art therapist is utilizing what’s there in the moment for that person and making decisions on how to help them help themselves recover, stabilize or find what is useful in their treatment plan, Massel says.

“Every therapy can be creative, but with art therapy there is the addition of the symbolic language.”

More than a canvas

For Young, while he recognizes that his struggles with depression are likely never going to vanish entirely, his ability to immerse himself in his talent and experience the kinship of fellow artists is comforting.

“I love to do art for myself and other people,” he says. “I also love showing it.

“I can express myself. That’s what I’d like to tell people, who, like me, deal with a mental illness.

“They can use art to feel better. It doesn’t have to be a Van Gogh. It just has to come from within them — something they can be proud of producing.”

The Twenty Years of Wellness Art Show is on display at the Richmond Cultural Centre on Oct. 8 from 6 - 9 p.m.